On April 16, 2000, tens of thousands of people gathered in Washington, DC to mobilize against the spring meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. This was one of a series of Global Days of Action against neoliberal capitalist institutions including the G8, the World Trade Organization, and the IMF/World Bank. At the time, opponents of these organizations were loosely described as the anti-globalization or alter-globalization movement; later, as the global justice movement.

While resistance to those institutions dates back to their founding at the end of the Second World War, this movement was arguably launched by the Zapatistas, a revolutionary insurgency in Chiapas, Mexico. The Zapatistas appeared on the world stage in an armed insurrection against the government of Mexico beginning on January 1, 1994, the day that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect—a trade agreement between Canada, Mexico, and the United States that bankrupted 1.3 million Mexican farmers.

People’s Global Action emerged from the Intercontinental Gathering of the Zapatistas encuentro in 1996. This provided a framework for organizing against neoliberal trade institutions, drawing together thousands of grassroots organizations, affinity groups, and anarchist collectives. These motley radicals were joined by traditional labor unions, environmental groups, Non-Governmental Organizations, nonprofits, and individual activists. It was a big umbrella, rife with contradictions, riven by messy debates about tactics and strategy, inclusion and identity, violence and non-violence. The goals of the participants ran the gamut from reforming neoliberalism to destroying capitalism.

After the world-famous demonstrations that shut down the World Trade Organization summit in Seattle in November 1999, preparations for the IMF/World Bank meeting in April 2000 spread the momentum to the East Coast, showing that the events in Seattle were not an anomaly but a stage in the emergence of a powerful movement. In a series of spokescouncils, protesters planned to shut DC down with blockades; in the end, the police effectively conceded the city to protesters by shutting down a massive portion of downtown themselves.

The following oral history brings together the experiences and voices of some of the participants in the actions of A16.

A delegate trying to reach the IMF/World Bank meetings, flanked by demonstrators from the black bloc intent on stopping him. This photograph, the header photograph above, and others herein were taken by Orin Langelle, a documentary photographer and activist and the co-founder of the Global Justice Ecology Project. You can see more of his photographs here and read more information about him below.

Table of Contents

- Children of the Zapatistas

- Millions for Mumia

- Building Momentum

- Dreaming of the End of Neoliberalism

- N30 Seattle

- Taking on the IMF and World Bank

- Hitting the Ground Running

- Diversity of Tactics: Marching Bands, Blockades, Flying Squads, and Radical Cheerleaders

- A16: All Together

- Get Those Animals Off Those Horses!

- Jail Support after A16

- A16 Was My Baptism

- Further Reading: 23 Years of Counter-Summit Mobilizations

These anti-WTO protesters are a Noah’s ark of flat-earth advocates, protectionist trade unions, and yuppies looking for their 1960s fix…

-Thomas Friedman, New York Times opinion writer Senseless in Seattle

From his point of view, that’s probably correct. From the point of view of slave owners, people opposed to slavery probably looked that way. For the 1 percent of the population that he’s thinking about and representing, the people who are opposing this are flat-earthers. Why should anyone oppose the developments that we’ve been describing?

-Noam Chomsky, Author, linguist, and anarchist in response to Friedman

Children of the Zapatistas

Our narrators arrived at A16 from a variety of backgrounds and points of entry.

Ryan: The older activists and organizers who especially influenced us, as young anarchists in DC in the late ’90s, were people of color: folks in the Black community who organized around Mumia and police brutality and Indigenous organizers working on freedom for Leonard Peltier. There was a lot of that organizing happening at the time and they were super supportive of us as young activists and approached us as mentors. We saw them as elders, folks to learn the ropes from.

Ben: In 1992, we saw the videos of Rodney King. And those cops were beating him down. We were at Claremont College, and every white pudgy-faced cop was let off. I remember thinking “Holy shit!” and I saw the campus emptying out. It was a raw, sick in the stomach feeling. I remember things starting to burn. One of my friends was dancing and screaming “It’s been 400 years!” And it just expanded all across Los Angeles. I remember looking at downtown LA and seeing flames going up in the air. That was not a march!

“It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” was already out. Does life imitate art or art imitate life? “Straight outta Compton” was the soundtrack, with “Fuck tha Police.” We were listening to that all spring before the riots. And these movements were raw, that was the moment I realized that history was alive. I’d had this sense that history doesn’t happen in the United States, it happens far away, but wow, history was happening right here.

Gabby: I was raised by two old hippy militants who got burned by the COINTELPRO operations, they felt very betrayed by the movement they were a part of. Because of their disillusionment with that, they were very dismayed when I got involved with politics, but I basically grew up a red diaper baby. I grew up being pushed around picket lines in my baby stroller, with my dad and with my mom, to pro-choice marches. But I didn’t really learn about my parents’ radical youth until I started getting arrested at protests and hanging out with no-good anarchists.

Panagioti: I was living in a trailer park in Florida. I’d dropped out of high school and was living with people who decided to participate in youth anarchist organizing. We were doing local organizing, stuff like Food Not Bombs, Zine Distros, local shows.

Vikki: I went to high school in Jamaica, Queens. And now we’d consider that a school-to-prison pipeline school, this was the 1990s, so we didn’t really have the language then to describe a school that was Black, Brown, and mostly immigrant; it was under-resourced and underfunded. It had a bunch of school security guards, you had to go through metal detectors every morning and put your bag through an airport scanning X-ray machine. It was like going to jail, every single day.

There were several thousand kids there, super overcrowded, and it was a perfect recruiting ground for gangs. And a whole bunch of my friends joined gangs, dropped out and got arrested for gang-related activity, mostly armed robbery. Because their families didn’t have any money and they weren’t able to post bail, they ended up in Rikers. That was my first “What the hell is this?” awakening.

I started to go and visit them at Rikers. I had to bring an adult with me each time because I was only fifteen and you weren’t able to visit by yourself until you were sixteen. I spent a lot of time in the Rikers waiting room: three hours if you went at the earliest time if you woke up at 6 am, or you’d spend six hours waiting if you went later. I would end up talking to all these other people who were there for their loved ones. It was mostly Black, Brown, and immigrant women waiting to see the menfolk in their lives.

Pica: I was a college senior, majoring in history, destined for jobs as a barista and labor organizing. I feel like we were the children of that period of time, children of the Zapatistas, we really had to try and make our town better and build community.

Lelia: I grew up in an activist house—my parents were activists, we had lots of roommates who were activists, it’s just sort of what I thought people did. If there is something going wrong locally or nationally, we need to do something about it. As soon as I got to college, I hit the ground running and joined every activist group that there was.

Mark: I became politically active the first semester I got to college and that was the South African Divestment movement, in its full flowering. I’m an older Gen Xer, so I went to Hamilton College in 1986. The Divestment movement was probably at its peak then. There was an occupation in the President’s office that Fall, thirteen students were expelled from the college. It was pretty militant, everyone involved in the Divestment movement wore black armbands on campus, we had whistles. There was a pretty substantial right-wing reactionary student body, fraternities and hockey players, your typical meatheads.

Nicole: I grew up in New York City, so in high school, there were multiple scenes, there was a lot of organizing around Mumia Abu Jamal and police brutality. In my senior year of high school, I went to what later became the Left Forum. I also went to some workshops based on Paolo Freire, which was cool.

Back then, there were always people tabling with literature, where people shared with me that there were protests happening around the Community Gardens in the Lower East Side and all around the city. Giuliani was auctioning them off, so I went down to Tompkins Square Park, right on time to join my first Reclaim the Streets protest.

R. Harvey: My first experience in being politicized was probably listening to the Clash and the Dead Kennedys when I was 13. When I was 14, I got into vegetarianism, as we did back then, going vegan. I got into animal rights very early on, getting PETA to send me some signs.

Gil: For A16, I planned a poster to carry with me as I wandered the streets of DC. I was arrested there in 1972 when there was a police riot under the directorship of Tricky Dick [President Richard Nixon].

Ryan: At Positive Force meetings, there would be a handful of people who attended to represent another group, asking for time on the agenda. They would run down something that you’d learn on a post now. The upcoming protests against the IMF meetings in ’99 or an upcoming Zapatista solidarity thing or whatever.

They’d come with a bunch of literature and you’d leave with a stack of paper. Then you’d go home afterwards and look through everything, information similar to what you might access through a social media feed now.

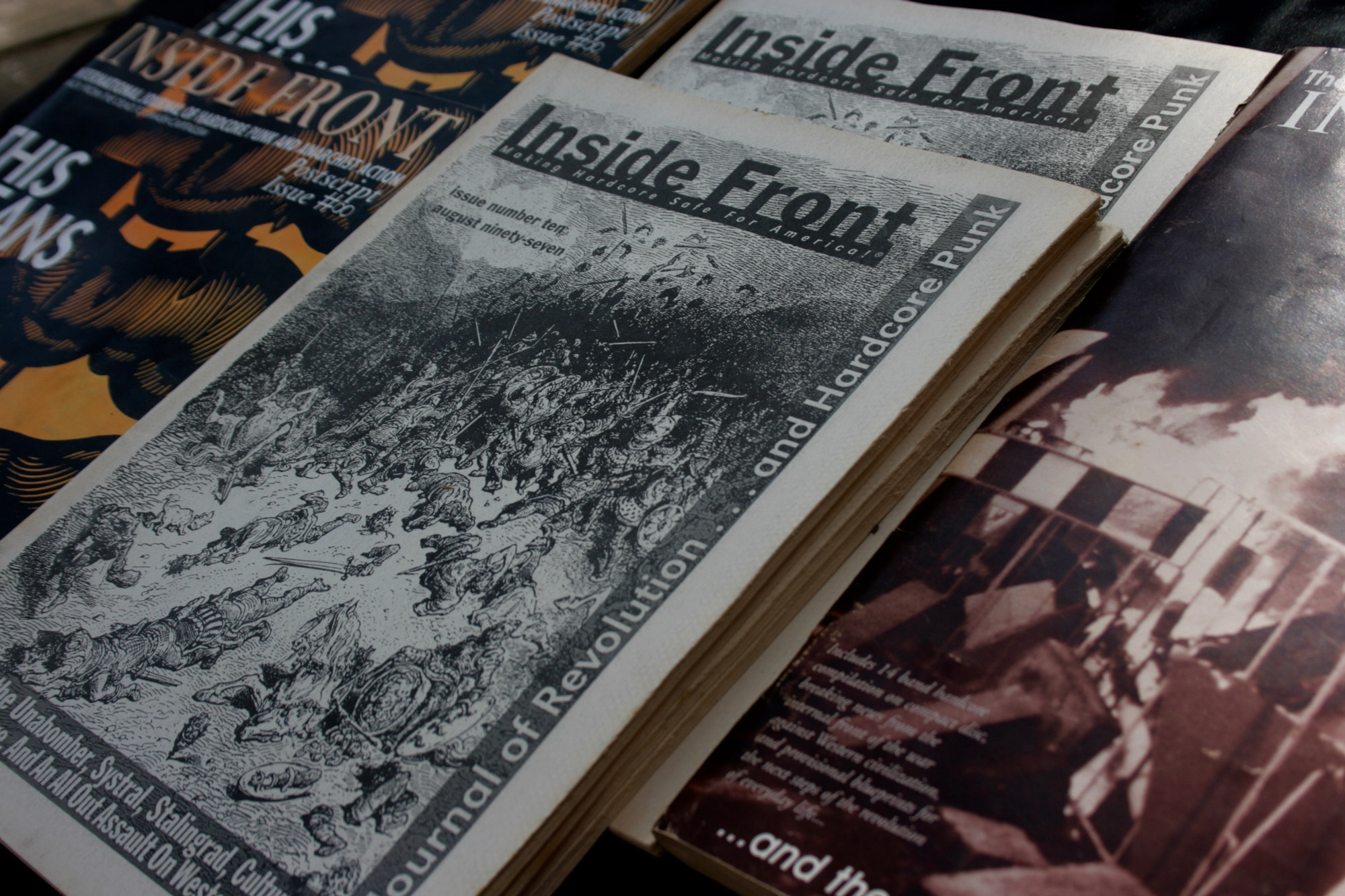

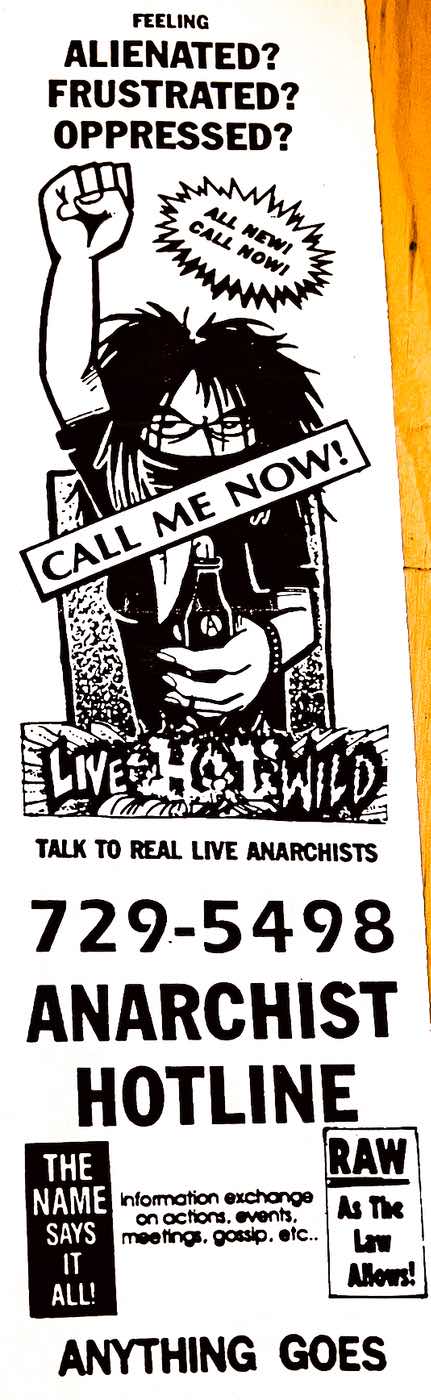

Before the age of widespread digital access, anarchists in New York City maintained a telephone hotline to connect people to local organizing.

Millions for Mumia

Another crucial thread drawing people together was support for political prisoners, especially from Black and Indigenous movements. The campaign to free journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal, facing execution in Pennsylvania, provided a rallying cry against the systemic racism of the United States legal system.

R. Harvey: With Mumia, you know, the role that Leonard Peltier and Mumia Abu Jamal played in our movement, these were folks from the 1970s and ’80s; the reason why people knew about them were the Black Panthers and MOVE, they never let people forget about Mumia. Who knew that they would have a side effect of politicizing the people who went out to confront globalization?

Lelia: We went to Philly—I feel like we went to Philly a lot for Mumia stuff. Jericho Movement, that was huge. I don’t really remember much, other than the sea of people and the chant:

“Brick by brick

Wall by wall

We’re gonna free

Mumia Abu-Jamal”

Gabby: I was heavily influenced by the Zapatistas, I used to do Books through Bars, went to marches for Mumia, prisoner support. It wasn’t a world I was living and breathing every single day, but I remember going to Philly for Mumia. I remember the “brick by brick” chant, I was thinking that this was the best protest chant I’d ever heard.

Anarchism has a long history in Philadelphia. A flier for a gathering in 1993.

Jimmy: When I was in San Francisco for the Food Not Bombs in 1995, one of the most amazing things that happened was this really militant torchlit march for Mumia. He was on the kill-list, they moved him up on the execution timeline and they had a date for killing him. There were protests across the country.

Those San Francisco and East Bay anarchists, they really did us proud! We’re marching right up Market Street, through the construction zone, knocking over barricades, picking up shit to throw if needed. And bicyclists are coming down all the side streets in support, with bundles of torches, dropping them off at the street corner for the march. It was intense. People along the route were so excited, hanging out of windows, cars honking for Mumia. We’re telling people and passersby “Come on, join us!”

So we marched through the Castro. I was running with people I met at the Chicano Youth Center, an infoshop-style place, these Chicano punk teenagers and anarchists, this woman Red Moonsong, who was a queer radical grandmother anarchist hippy. The cops freaked out and started to counterattack. Red Moonsong, I remember her saying “Um, this is the part where grandmothers leave.” Later, you know? So, she dipped out. Me and the dude from LA were folding up the big Food Not Bombs banner we had, stuffing it into a backpack, and the concussion grenades were exploding around us.

Ben: I was writing my novel, my roman à clef, in the Kilowatt, or maybe it was 500 Club, by the Roxie, somewhere on Valencia Street in San Francisco, working on the notes in my journal. And I heard some shit going down in the street outside, I was like “What the hell is that?” and it was going against traffic. I asked someone, what’s going on? And they said “March for Mumia!” And I was like “Who’s Mumia?”

People were screaming and somersaulting and jumping between cars. They weren’t exactly breaking things but there was a feeling—is this a march? Is this a riot? Besides ACT UP, I wasn’t plugged into anything. There was a rawness. And someone said that it was about the Prison Industrial Complex. Oh that! There was an immediate sense that this was a live issue. People are talking about Malcolm X and it’s a real thing. It’s not a past thing, they’re listening to the Last Poets, to Gil Scott Heron, “The Revolution Will Not be Televised.” That album, along with “A Nation of Millions,” was the soundtrack.

Mimas: A major current of American activism in the 1990s was prisoner support and anti-police-brutality campaigns, especially around political prisoners like Mumia Abu Jamal. Through awareness of him, we also learned about the repression of the Black liberation radicals and anarcho-primitivists in Philly. The Philly police actually used an incendiary device, a literal bomb, and dropped it on the MOVE house. That’s how far they were willing to go to stop them, to literally kill Black people with bombs.

While awaiting execution, Mumia became a vital critic of the death penalty, an author of books and articles about police state and the criminal justice system, with his supporters campaigning for his release from prison. He also had a coolness, a sense of calm righteousness that truly captured our hopes and aspirations for a better world. Many of us were radicalized by or otherwise supportive of Mumia, prior to and during the anti-globalization movement.

Vikki: When I wasn’t going to this arduous bus trip to Rikers, I’d make the trek to the City [i.e., Manhattan], go to St. Mark’s Books. I’d just stand in their prisons section and read these things because I didn’t have enough money to actually buy these books and everything there.

I realized that this is not a system that is broken, that it’s actually functioning as designed. The system is designed to monitor, control, and to surveil these Black, Brown, and immigrant bodies. That’s why the waiting room and the visiting room looks like the way it does; that realization in the Rikers waiting room was my politicization.

R. Harvey: I went to Millions for Mumia on April 24, 1999. That was my first big protest. I was in the anarchist punk scene in Baltimore, I was from Towson, where we had our own scene. We were listening to local bands, bands like Aus Rotten, A//political, Anti-Product, these kinds of groups and they were talking about these issues.

Ryan: Millions for Mumia was a big one for us. It was the first black bloc I was ever in for sure.

Millions for Mumia.

Building Momentum

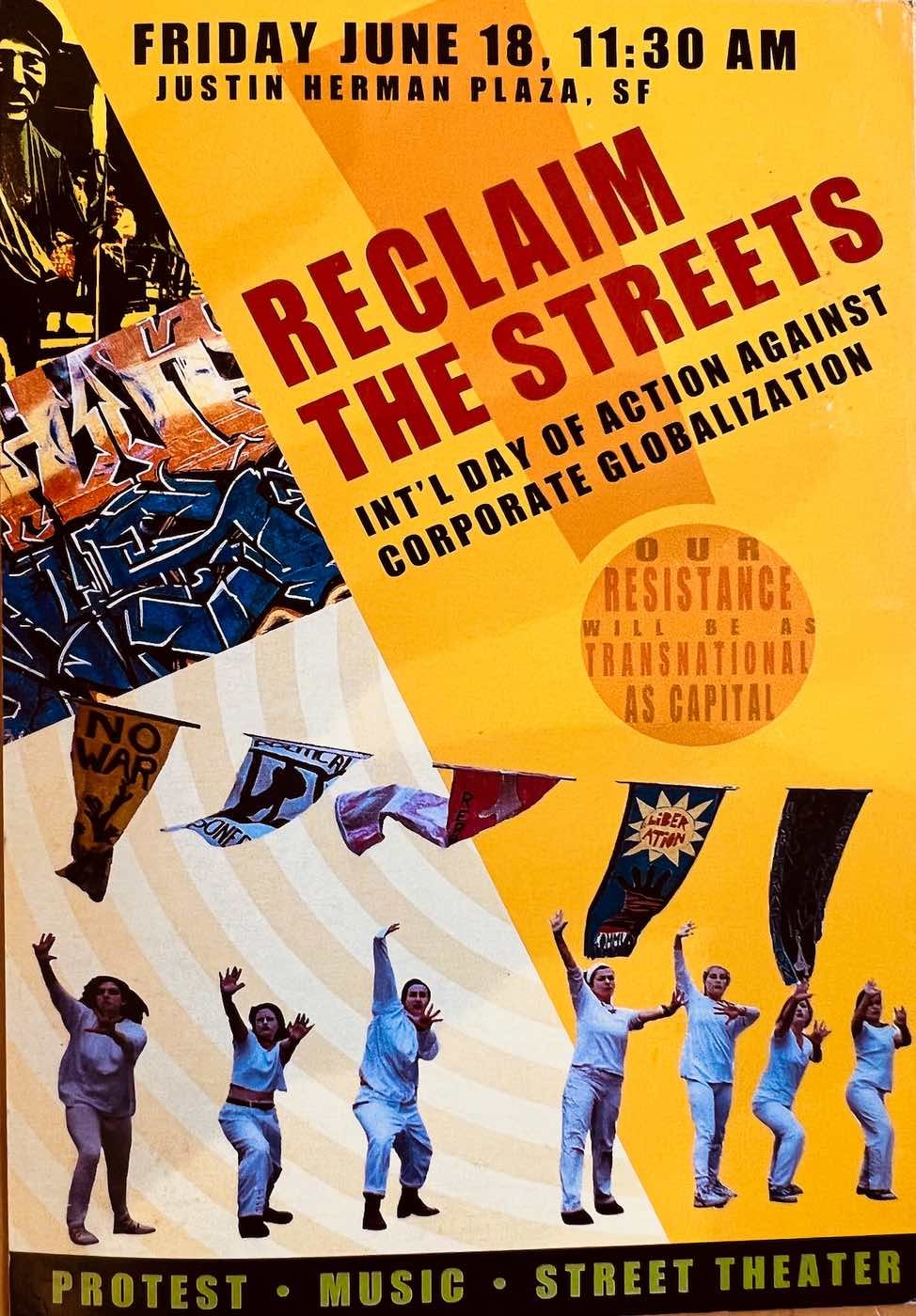

In the United States, activists began to align themselves into a movement, gravitating around Food Not Bombs, Critical Mass, Youth Liberation summits, Earth First! campaigns, Reclaim the Streets actions, Latin American solidarity movements, and campus organizing. The international day of action on June 18, 1999 marked the convergence of many of these currents.

Mark: Prior to Seattle, there was the G8 meeting, which happened on June 18, 1999. Reclaim the Streets was a global formation that started in London, specifically around the M11 link road and the rave protests—the anti-roads movement and the anti-rave legislation that had been passed. They later went to work with the dockworkers and so forth, but they really jumped into and were formative in the Alter-Globalization movement. It then spread across Europe through the Reclaim the Streets form, so in New York, we were paying a lot of attention to Reclaim the Streets UK.

It was the early days of the internet, but Reclaim the Streets UK had one of the coolest websites you’ve ever seen; it’s archived somewhere. It was basically a Borges “Garden of Forking Paths” structure where you could get lost in it; lots of quotes from Abbie Hoffman, the Diggers, and the Levelers. The images were just incredible.

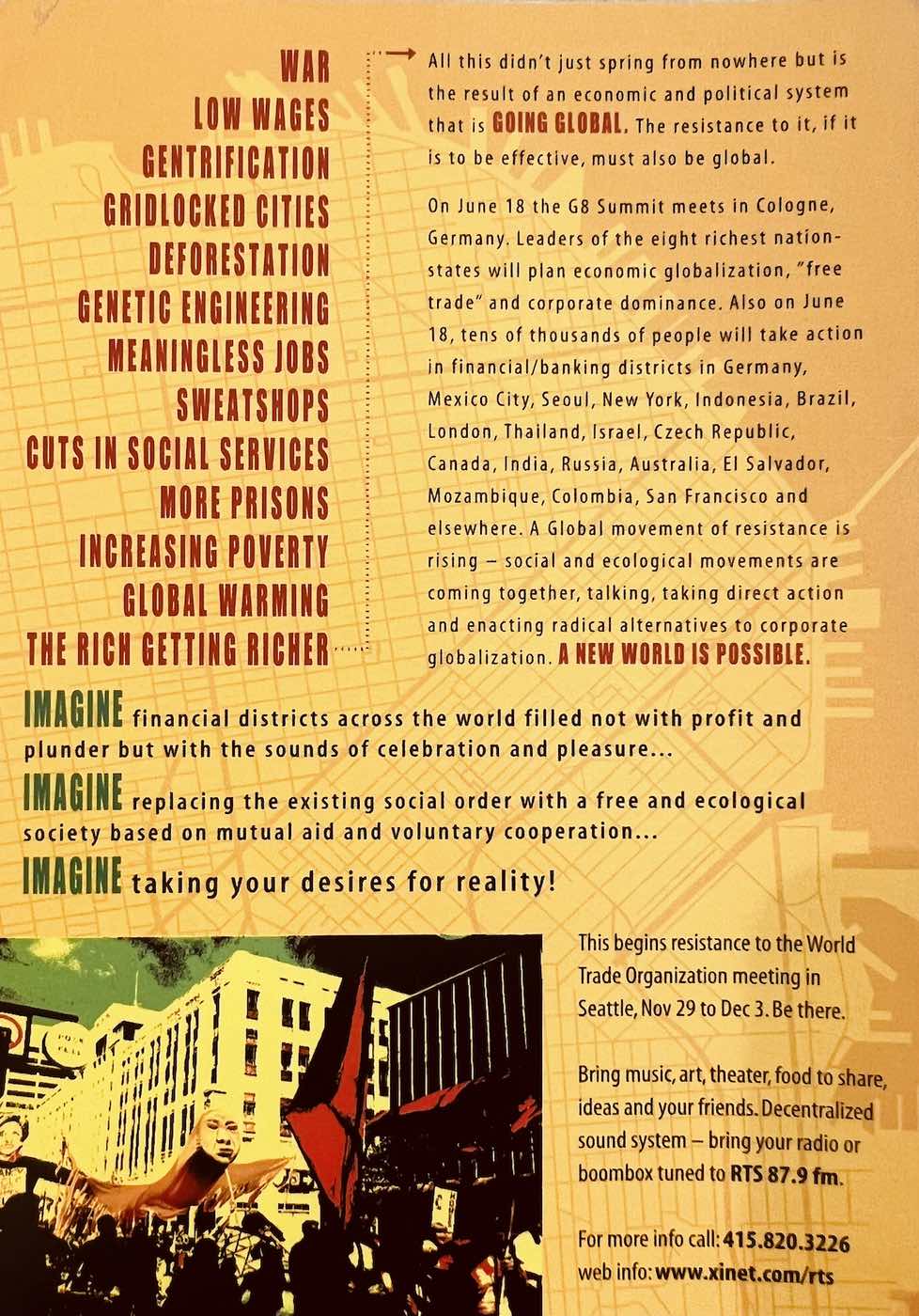

The rave aesthetics of the J18 organizers in London are exemplified in this palm-card distributed to promote one of the rallies.

Nicole: That was my first time seeing protests like that, before you could get news from social media or the internet. I hadn’t been exposed to those kinds of images at the time, the radical far left. It always felt good, whether it was Reclaim the Streets or Critical Mass, to be in the streets.

What always felt really powerful was taking the streets and changing the narrative of what things should be like. Any chance to change your thoughts and make a cleavage with what normally is; that was really attractive to me, especially when it comes to saving the planet or helping people that were oppressed.

Ben: I remember Food Not Bombs was so great locally in San Francisco, because they were risking arrest all the time for the critical offense of giving food away… how could anybody think they were a hindrance to the quality of life?

Food Not Bombs prefigured a whole movement with their name, like the More Gardens! Coalition or Housing Works. It’s very relevant. “Food not bombs?” It’s very hard to argue with.

Gabby: Food Not Bombs was really important. When I was traveling, I knew I could show up anywhere with a Food Not Bombs and meet people and figure things out. Or, is there an infoshop in this town? There was a whole network and infrastructure. I slept on so many floors around the country.

I also spent a lot of time at ABC No Rio, I was definitely involved with bike culture, riding Critical Mass. Later, when I was tree-sitting, I’d sit in my tree and dream of Critical Mass Rides in New York City.

ABC No Rio, a squatted venue in the Lower East Side, was one of dozens of community centers and infoshops across the country that formed the infrastructure of the anti-globalization movement.

Vikki: Because I didn’t have friends to hang out with, because they were locked up, I started to coming down to the Lower East Side to ABC No Rio and Food Not Bombs. From there, I fell in with a bunch of punk rockers who were really political. And it was really eye opening, the idea that you could be an anti-authoritarian! That was not something I would have thought about before, instead of going to law school or medical school to be successful, which is the immigrant narrative that a bunch of us are fed. So if you are reading, you have to read things that get you closer to law school or medical school.

It was eye opening that you could be anti-authoritarian, that the system was fucked up. But I was still this bookish kid who liked to read about things, so you could actually be smart and like books, but it didn’t mean you had to follow this capitalist program. The women there, especially, at ABC No Rio kind of took me under their wing, would take me to this or that thing. That brought me even further into political organizing, when I was 17 or 18.

Ryan: I remember getting a postcard for the Carnival of Chaos, J18 at an event in downtown DC; I think it might have been the spring meeting of the IMF in 1999. The protest was small, like 50 people outside their headquarters, they were passing out things about the Carnival Against Capitalism, and different events.

Those 50 people protesting the IMF in spring 1999 mostly worked for NGOs, walking down the sidewalk trying to take the street a little bit. Shortly after J18 was Seattle, then A16, with tens of thousands of people for the same IMF meetings just a year later.

On June 18, 1999, the most well-known demonstration took place in London, but in fact, actions took place across the world, including this one in San Francisco.

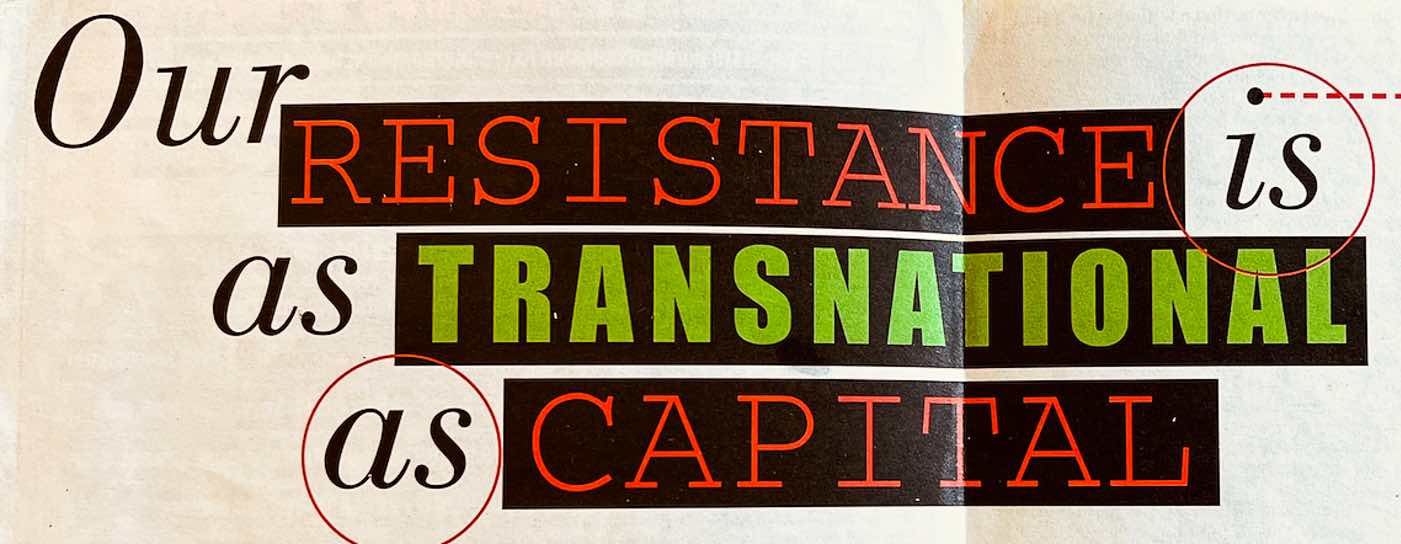

Mimas: A set of protests was called to coincide with the meeting of the G8 in Germany on June 18 that year, which brought together the leaders of the world’s wealthiest democracies (the G7) plus Russia. As early formation of the anti-globalization movement, J18 kind of created a template for later actions, its slogan was “Our resistance is as transnational as capital.”

The London protests in particular drew wide attention with the street carnivals, samba bands, Critical Mass bike rides, and blockades of corporate headquarters. Other international protests also took place on J18 in Canada, Australia, and Nigeria, where they shut down Shell oil infrastructure, as well as dozens of actions across Europe and the US.

Back here in the US, those involved in J18 protests and those in Seattle were more likely than not also participants in movements such as Food Not Bombs, Critical Mass, Reclaim the Streets, Earth First!, the Ruckus Society, and international solidarity campaigns. Those pre-existing actions and groups became fertile ground for the American iteration of this global movement. Back then, each country was a little different in how they approached the fight in terms of rationales, but we had a common target—the neoliberal institutions that supported the expansion of inequity and exploitation around the world.

“Our resistance is as transnational as capital.”

R. Harvey: The Carnival against Capitalism in London was taking a lot of inspiration from the No Roads Movement, which came out of the anti-nuclear movement. Crass was really inspired by the anti-nuclear movement.

Panagioti: We were doing youth liberation summits and Mayday gatherings back then. I’d see the same people in slightly different circumstances, doing and talking about the same things.

I remember these videocassettes of the forest occupations at Cove Mallard in Idaho back in 1996, seeing people using lockboxes and tripods. We had a crusty old copy of the video from Whispered Media, they were an IMC predecessor. We probably showed that thing 50 times at different conferences, workshops, and trainings to let people know what was happening. We amassed a collection of those videos.

The idea would be that you’d bring videos you’d collected along the way, gather 20 people together in a room, then eat mediocre vegetarian food and watch this video to find out what was happening.

Mark: I was involved in the first Critical Mass bike rides in San Francisco for several years after I moved there in 1992/93. I didn’t meet Chris Carlson until many years later, but I’d show up at the Embarcadero at 5 pm on the last Friday of the month, like a bunch of other people. My buddy Sheffer ran a bike shop called Pedal Revolution and he was making Frankenbikes, crazy tall bikes.

These rides were really celebratory, really goofy, I don’t remember in those days any conflicts with police. That might have happened later on, when things got edgy at times. We’d always wind up on a beach somewhere, smoke some weed, hang out with the Mothers of Perpetual Indulgence and Cacophony Society people, the latter stages of those people. I didn’t know what I was doing, just that my buddy made these tall bikes in the Mission and I was going along. They were really just a blast, just really very fun.

The reverse of the poster promoting the demonstrations in San Francisco on June 18, 1999.

Nicole: I got really involved with environmental activism, local issues like the community gardens. I started going to the Wetlands Center, working with people who did anti-Gap and Banana Republic campaigns, because they were destroying old-growth forests. This was the time of anti-sweatshop organizing, that was very big in campus activism.

Ben: My dad’s best friend died of AIDS. I started going to ACT UP demonstrations, and it wasn’t just a march, it was going to Sacramento for a direct action. There are some drag queens on the way, there are people carrying the ashes of their lovers that they are spreading and throwing at the cops. The cops rushed them, there was screaming and crying. Ashes in the air, then we’d go out for a drink and have a great time. There was a march, and a funeral procession, and then we’d go dancing. That was ACT UP. Activism was a practice; it wasn’t an identity.

AIDS activism was always my driving force, but after the Rodney King riots in Los Angeles, they started to build South Central Farm. I saw it as a prefigurative community-building gesture that was bringing people together to share space, to share food, to share histories.

That garden was a big common space that people shared. There was a lot of food and a lot of healing. When people get together and share a space outside of capitalism, where no one is arguing about who owns what, we can build a space together. People can do really beautiful things.

Getting back to land is belonging. We have this industrial idea that we’re supposed to be surrounded by concrete, but touching earth is important for human beings. bell hooks’ book about belonging is all about going back to Kentucky because the dirt called her: “This is my home, this is my people, we’ve been farming this land for a long time.” And I think people have a raw sense of connection when they touch the earth.

Radical queer activists played an important part in the anti-globalization movement, just as gay and lesbian liberation activists in the 1970s served as inspiring antecedents.

Pica: Community gardens were really magical places in every city you’d visit. That sounds corny, but if you ever spent a sunset in one with friends, with a fire, or someone making food in the casita… You got legitimate cultural exchange, locals hanging with the weird travelers from all over, with outcasts and rejects.

Ben: I really fell in love with the movement in New York in the ’90s. I’d walk to the subway to go to the Bronx from the East Village and I’d see these little patches of land as I walked by. And I thought, “I love these spaces.” You can just sit down, nobody cares, with whatever you’re bringing in, you could eat your dinner and have a coffee.

The gardens movement in New York City was a food security movement. There were Black Panthers involved in that, Young Lords, there were a lot of through lines to the community empowerment movements. And there were the squatters! The squats and the gardens overlapped and when the squatters showed up, you knew you were going to have power.

I hate this term, “green gentrification,” but gardens do improve neighborhoods. They increase the number of eyes on the streets, that’s what Jane Jacobs said. You need people to look at the neighborhood. You don’t need cops; you need individuals in the community looking in the streets to make sure everybody is OK. But they do increase property values because people can sell you a building, and say “Look at this beautiful green space that the neighborhood made, right around here.”

Lelia: At American University, one of the compelling groups was the Free Burma Coalition. At the time, there were four student activists who were arrested for leafleting in public, just passing out papers to people. It was the first thing I signed up for as a freshman.

It wasn’t just at AU, it was all over. There was a big Burmese population there, folks who had to leave their country, living in the DC community. There was intergenerational activism; we had letter writing, benefit dinners, fashion shows—that’s funny to me, because I’m so not fashionable. We also did civil disobedience.

We had this long campaign with letter writing, including all the proper quote-unquote “steps,” and we began thinking on what we have to do to move down the chain of demanding more action. I arrived at school, in maybe August, and I was arrested by October—I had decided that it was enough letter writing for me and it was time to move to civil disobedience. We had a divestment campaign as well, getting the university to stop doing business with certain companies.

Mark: I landed in NYC in the fall of 1998, I came to do grad school at New School. Just before I arrived in New York, I’d been to Bread and Puppet Theater, in Glover, I’d been going there since 1994. I was puppeteering and I met Aresh from More Gardens! in the costume room in the barn, and Trudy and John from Great Small Works, of course, and the Bread and Puppeteers. They were really involved in the community gardens struggle in that moment, and Charas El Bohio community center, which had been auctioned off.

And then it was Steve Duncombe, who guest-lectured in a media studies class I was taking at New School. He talked about Reclaim the Streets, and I was like, “Hmm, tell me about that.”

Ben: By 1998/99, there was an action every week in New York, whether it was a garden action, or a Fed Up Queers Action, ACT UP. I remember when Matthew Shephard, the young college student in Wyoming, was killed, we tried to have a funeral march in Manhattan, and Giuliani tried to arrest all the organizers and wanted us all to be on the sidewalk. 5000 people don’t fit on the sidewalk, Giuliani!

If he would have let us march for an hour, we’d have gone to the bar afterwards. But no, he swept everyone up, and everyone went to jail for the night and the next day, your friends are doing jail support. We were covered in the New York Post and the Daily News, and I was arrested with Charles King and Keith Kyler from Housing Works. And Sylvia Rivera was in the pen with me, when we were all daisy chained together with restraints. Michael Cunningham, who had just won the Pulitzer Prize for The Hours, was with us. There were epic groups of people together and every week there was another action.

And then we started hearing about the rumblings of [the mobilization against the WTO ministerial in] Seattle in Adbusters. We planned our solidarity march with Reclaim the Streets. We had one to save the gardens, and another to Times Square. I think people thought it was an MTV video, so they left us alone. Mark got really badly beaten up by the cops. You’d do jail solidarity, with yoga going on outside, and then people got straight out of jail to go to the airport for Seattle.

Nicole: In New York, right before the demonstrations against the WTO in Seattle, there was a big Reclaim the Streets action. That Reclaim the Streets was one of the most exciting protests I’d ever been to at that point; we showed up to Union Square, and then had a subway party, with people in costumes, people hanging from the bars on the subway. People dancing and singing, we got up to Times Square, then, later, Bryant Park. It was massive, people taking over an intersection. There was even a tripod, this was the early days.

Vikki: Seattle was visceral, people were on the streets and they were fighting. When I first got to the Lower East Side, one of the things that really drew me in was that it was the tail end of the large-scale squatter movement. I came in right after the 13th Street squat [was evicted] with a tank, so those two were linked in my mind.

Anarchist organizing and outreach in New York City before the age of digital connectivity.

Dreaming of the End of Neoliberalism

Prior to the Zapatista encuentros, the institutions driving neoliberal adjustment—the WTO and its precursor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the IMF and World Bank—were obscure entities. By targeting their annual meetings and ministerials, activists took the abstract phenomenon of neoliberal globalization and made it concrete. You can’t abolish capitalism with a bullhorn, but with 20,000 of your closest friends, you can disrupt a meeting of bankers and bureaucrats.

Eric: After World War II left Europe devastated (and centuries of colonialism and resource plunder had severely damaged what is now called the “Third World”), a conference was convened at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in 1944 to create institutions separate from the United Nations that could oversee the regulation of international trade and assist in the building of Europe. The result was the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which became the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The stated goal of the World Bank was to aid Europe’s reconstruction and help to develop poor countries around the world. The original mandate for the IMF was to facilitate global trade while leaving countries free to establish their own economic guidelines.

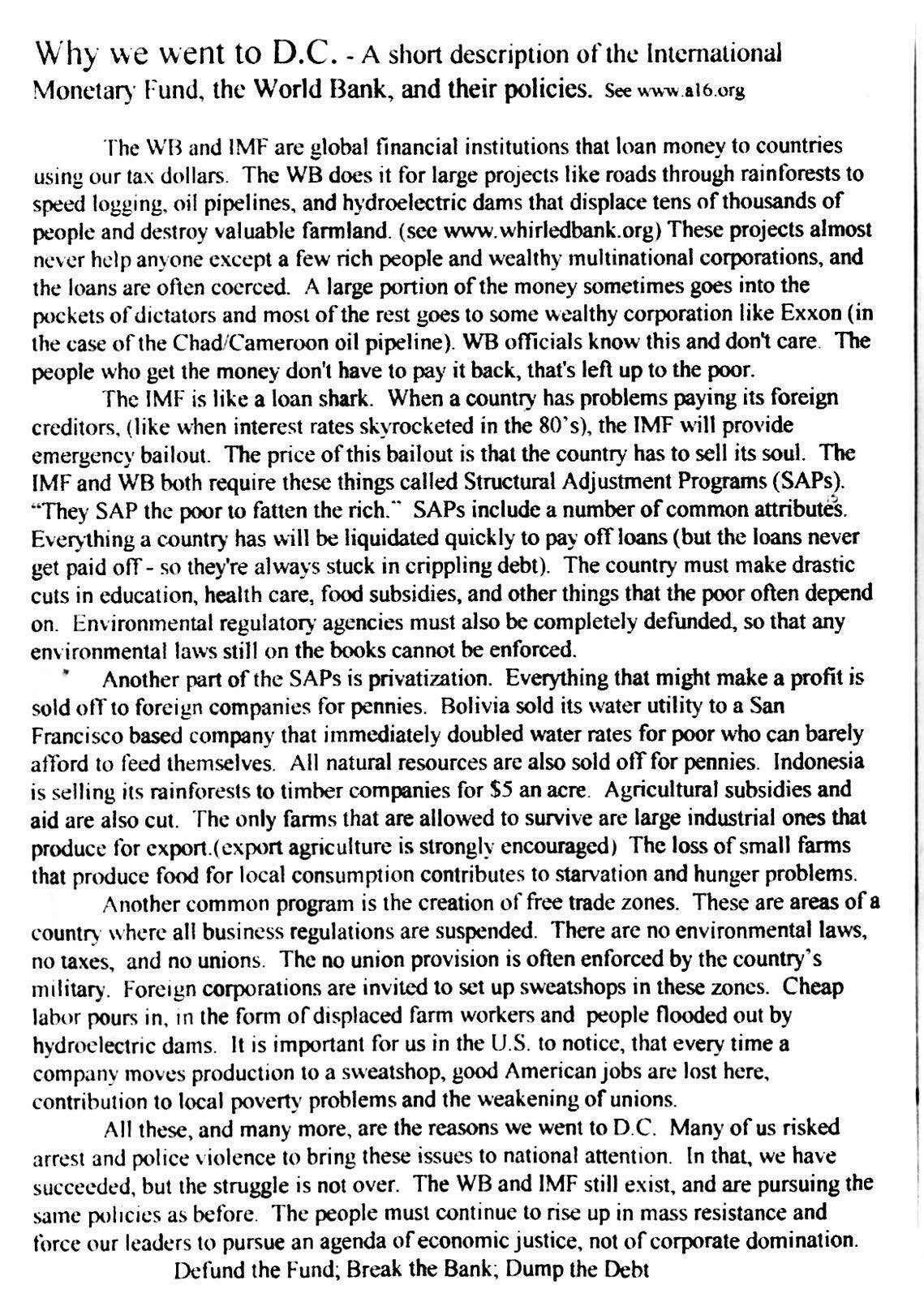

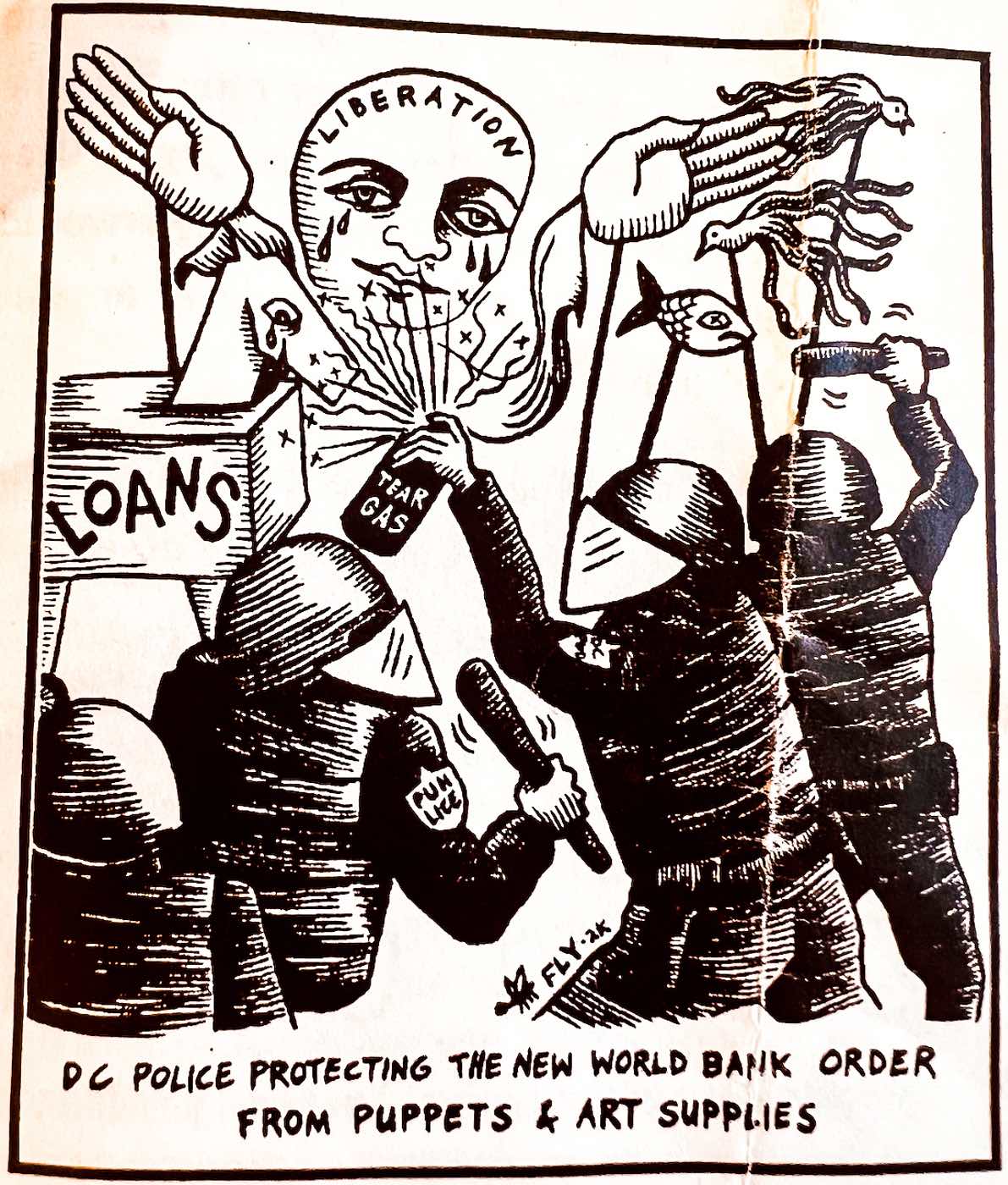

A16 protest flyer distributed at the Convergence Center in Washington, DC.

The IMF is like a loan shark. When a country has problems paying its foreign creditors—for example, when interest rates skyrocketed in the 80s—the IMF will provide an emergency bailout. The price of this bailout is that the country has to sell its soul. The IMF and WB both require what they call Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs). “They SAP the poor to fatten the rich.” SAPs include a number of common attributes. Everything a country has will be liquidated to pay off loans—but the loans never get paid off, so they remain stuck in crippling debt. The country must make drastic cuts in education, health care, food subsidies, and other things that the poor depend on. Environmental regulatory agencies must also be completely defunded, so any environmental laws that remain on the books cannot be enforced.

Another part of the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) is privatization. Everything that might make a profit is sold off to foreign companies for pennies. Bolivia sold its water utility to a San Francisco-based company that immediately doubled water rates for the poor.

-A16 protest flyer distributed at the Convergence Center in Washington, DC

Ben: AIDS activists went to Charlene Barshefsky’s office, who was the US trade representative. And they told her that she had to change the United States drug policy. You had the World Trade Organization rules that said that you can actually, in the healthcare crisis, create your own drugs, generics, and yet you’re suing South Africa that has a health crisis with AIDS going on.

To me, the IMF protests were all about amplifying that injustice. I didn’t think we were going to stop the meeting. I think you had to make clear that what was happening in the meeting was bad and that if you care about health, you need to do this differently. They wouldn’t listen to us, or listen to anybody, if we played by their rules.

Did you know that Donald Rumsfeld, before he was Secretary of Defense, was the head of the Office of Economic Opportunity from 1969-71, under Nixon? That’s how anti-poverty programs become mechanisms of war—that thinking, using debt as a bludgeon. Literally the guy who pushed for the Iraq war started as a poverty guy. That’s the Herbert Marcuse idea—when the welfare state becomes the warfare state.

Pica: The people in Cochabamba and their supporters across Bolivia—farmers, workers, residents, students—weren’t going to let Bechtel destroy their lives by tripling the price of water. They had a massive rebellion, blockaded the main roads in the country, essentially shut down the country. They fought back because their lives literally depended on it. As we were planning for A16, the shit was going down in Bolivia. These policies were being determined in boardrooms and ministerial meetings here in the US, we had a moral obligation to fight them here, on their home turf.

Panagioti: Pretty quickly, the basics of economic globalization became known. By the time A16 rolled around, we had to understand the acronyms better. The World Bank and IMF seemed a little more complicated, having been around longer, than the WTO, which was new. I was really open to learning things really quickly.

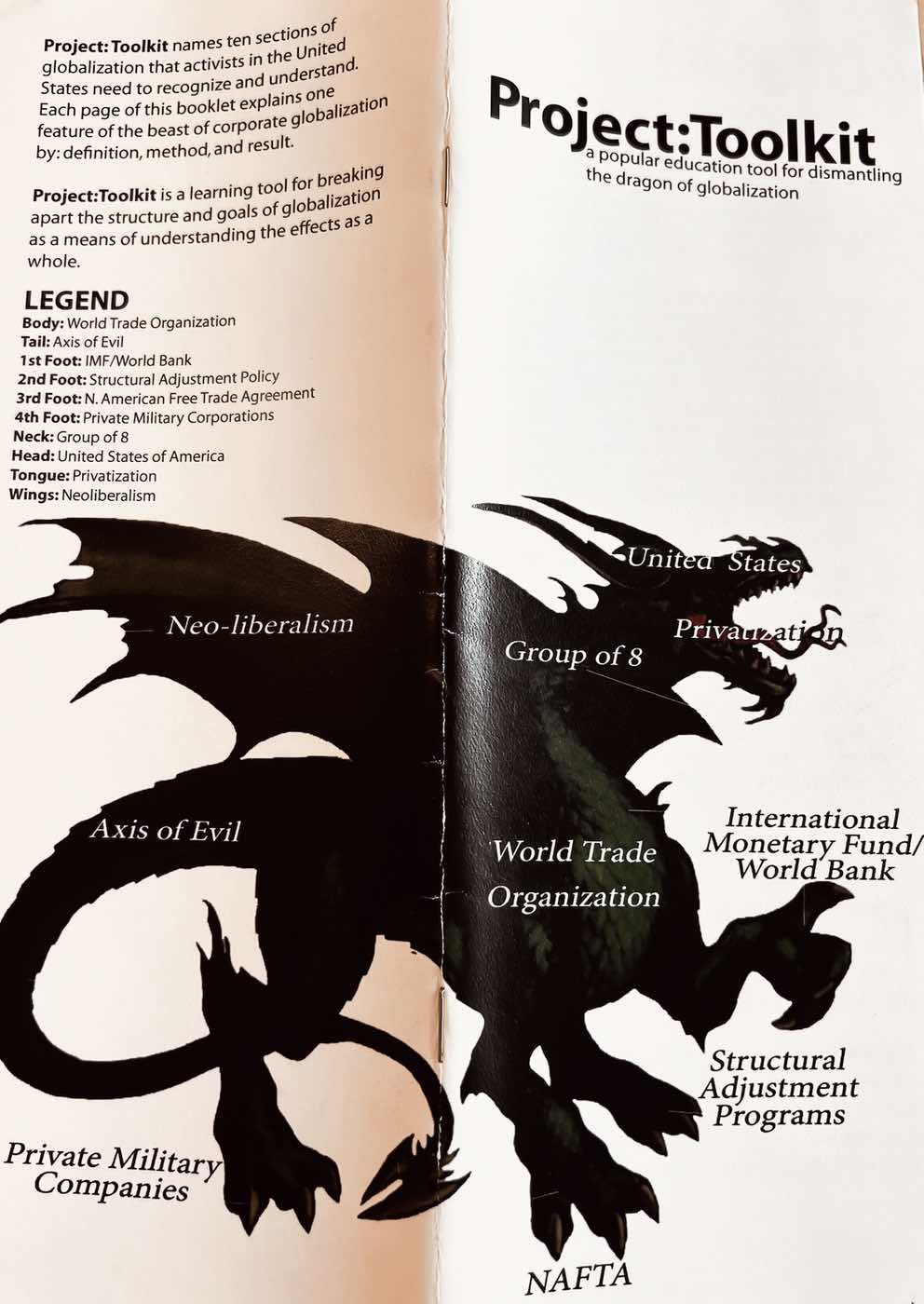

A pamphlet from the turn of the century critiquing capitalist globalization.

Mark: I remember going to see Life and Debt, the film by Stephanie Black, right around that time. To this day, it is a terrific description of structural adjustment programs as imposed on the island of Jamaica. It was very specific—what happened with the local milk production industry, the banana, all the trade policies that destroyed Jamaican farmers.

Eric: The debt is not the result of the will of the people; governmental agents, encouraged and instructed by local elites and foreign investors, were the ones who accrued the debt. These agents of capital are the ones who have received the profits from investments and pork-barrel spending, but it is the public who must pay the costs. The bailouts orchestrated by the IMF and World Bank pay little attention to such nuances.

If the government of Indonesia owes money to Swiss banks because they spent all their money buying tanks and bombs from the United States, then it is the people of Indonesia who must starve themselves and work for slave wages in order to pay it back.

The mass mobilizations are key to maintaining pressure on these institutions, and to creating the change we are talking about. It is quite impressive when you get millions of people saying, “Cancel the debt.” It is quite impressive when millions of people are saying, “Stop structural adjustment programs,” “Open your meetings,” and “Stop environmentally destructive projects.” It is quite different than when you just have a few NGOs who are not necessarily pushing hard.

Njoki Njoroge Njehu, 50 Years is Enough

An anarchist banner on A16: “Global liberation, not devastation.”

Pica: We knew we were seeing something special with this movement against capitalism, against corporate globalization. All of these groups and fights for justice, coming together—prison abolition, workers’ rights, queer activism, international solidarity, anarchism, feminism, campaigns to hold police accountable, all of it. All of our parallel paths came together arm in arm in the streets of Seattle and DC.

It was very common for people, especially in small towns, to support other projects and campaigns. You might be a labor activist, focused on workers’ rights and raising the minimum wage, but you’d kick it with the vegans and join the roadshow to watch a Chomsky documentary about the media when it came to town. People had a baseline of solidarity in left radical circles.

Gabby: As cool as things were in those days, I think I did a lot of FOMO. I felt like I grew up in the shadow of the radicals of the ’60s and the radicals of the Lower East Side, a place where a younger person could make a place for themselves. We still did it, we had a big squat called Camp C, it was unreal what we were able to get away with, it was like a square city block. The place was fucking huge.

The DIY scene in New York was all about hanging on to the spaces that were left as the city got more policed and more expensive, it was about being a place where you could go and make things happen as a person trying to live outside of the money economy. We built a whole culture around circumventing that money economy. It cheapens it to just say it was about our lifestyles because we built a whole world that was not about going through money to live our lives and have our needs met.

Nicole: This guy Tofu came to this conference at my college, he was a singer, I think he had been in Seattle. Also, there were the More Gardens! people who attended a political prisoners’ conference that we held. That conference was super powerful, Ramona Africa and Laura Whitehorn spoke there, they were amazing advocates who had been freed from prisons in the 1980s.

We would later see people we knew personally imprisoned because of their politics. All these things were happening in person, people had to come to these meetings to learn about these topics.

Ben: My favorite pre-Seattle action was against Disney. We went to the Disney store at Times Square and declared it our right not to live in a shopping mall. “Put down the mouse, put down the mouse” was our big chant. I’d never gotten arrested at a retail outlet for saying “Stop business as usual!” But I felt that we had a right to our own stories. Disney was sucking up our stories into their vortex. It was involuntary entertainment, we wanted to have a right to our own narratives. There was an absurdist defiance. It was fun, and Seattle became a part of that joyous moment.

Panagioti: In some ways, the formula to be an activist seemed similar to what I see now, but the process was so much more demanding. You’d read a flyer or pamphlet and go “Hmm, well, this makes sense.” And then, instead of just reposting it on Instagram, you’d go to a copy shop, make a hundred copies, cut and fold them and go to 20 different venues or coffee shops, hand them out or give them to people. Or make some stickers. The process of spreading information, and motivating people to mobilize—it was a lot more hands-on and tactile.

A flier promoting “Anarchist Soccer”—a euphemism?—in Milwaukee.

N30 Seattle

The protests against the World Trade Organization Ministerial in Seattle on November 30, 1999 were a watershed moment in the expansion of the movement.

Vikki: The internet was still kind of new and young and someone was like “Hey, I have a ticket to Seattle for those dates for the WTO protest and I can’t go. Does anyone want this ticket?” Neither I nor any of my friends knew what it was. We figured we’d do some kind of Reclaim the Streets or something in New York that same weekend instead. We didn’t know what the hell she was planning on flying to Seattle for, so I don’t know if anybody took her up on that free ticket!

And then Seattle happened and everyone was like “Holy shit!” and we started paying attention to globalization. I was focused before on things that were local or regional and the things that I could put my finger on. Police, jails, prisons? OK.

This larger idea of globalization? It didn’t occur to me to follow this, and people weren’t as online at that time, so you wouldn’t necessarily know about it from a morning newsfeed. Because of the “Battle in Seattle,” I started paying attention.

Pica: I had a few friends who went to WTO in Seattle. I couldn’t go because I couldn’t get off two weeks from my job. It would have been the bus, no way I could have afforded to fly there. I went to the reportback in my town afterwards in early December. I couldn’t believe it worked. At most, we could get twenty-five or fifty people to a protest; how do you pull off 50,000? Shutting down a whole city? The first thing I wanted to know was “When are you doing this again?” Because I knew I would be there.

Panagioti: I ended up in Seattle mostly having had read zines about globalization. When I got there, it felt, you know, like something close to a revolution, at least in my mind. I wondered to myself, “What if we didn’t go back home? What if we just stayed in these streets?” Looking back on it, maybe we had delusions, thoughts like “This is the Paris Commune of my youth!”

I had read these historical accounts of those moments of insurrection and I had this sense of participating in that, in some small way. It was accurate in one sense, but also absurd based on the short duration. These things we were doing were a couple days, instead of months of sustained occupation.

Mark: I had never been in that sort of situation before, what I saw in Seattle. I remember running to the Indymedia Center, I was there as a part of Paper Tiger TV collective, I was a media maker as well as a direct action organizer, and for Seattle, I was really focused on being a part of the TV production team for Indymedia. So we had embedded ourselves in a lockdown crew that included Carwill Bjork-James and Gopal Dayaneni; they were both in that lockdown.

“Breaking the Spell,” a documentary about the Seattle WTO protests.

Jimmy: Lars was there at the reportback for N30. I remember him returning riding high on a wave of anarchy, he had that song, “We are winning / Grab a bandanna for the tear gas cloud / Get organized and come downtown.”

Eric: The protesters in Seattle and DC were not, as many media reports claimed, confused kids with no place better to be who traveled in search of a good time and an expression of youthful rebellion. We took action because the policies of the IMF World Bank, and WTO are causing untold suffering, misery, poverty, and death.

We spoke out because we want to live in a world based not on greed and profit, but on human needs, equality, and economic justice. We want everyone to have food, housing, medical care, and a decent standard of living. In a world as wealthy and bountiful as ours, there is no reason for caring people to accept the suffering that exists all around us.

R. Harvey: As November approached, I remember distinctly being at an A//Political show in a row house in Baltimore. I think they were playing with Anti-Product and they were passing out flyers. Basically, “We’re going to destroy Seattle” with a picture of punks dancing on the city. Typical imagery of that time period. They had a song called “Whose Trade Organization” with very explicit anarchist punk lyrics.

That’s how I started to learn about it, but it wasn’t until the protests started to happen in Seattle that I went “Oh my god, they weren’t joking around. This is a real thing.”

Lelia: I remember really wanting to go to Seattle. We put money in a pot and we decided we’d send representatives from DC to Seattle because we couldn’t all afford to go. I remember Dave going for our group. I remember thinking, “This is our moment,” that we had been working up to this as activists for all this time. It was really neat to have so many of us coming together, labor and environmental folks in the same space was really powerful—not to say they were always at odds, but they can be.

Debriefing was part of the deal for the folks we sent to Seattle: we want to hear about everything they experienced when they came back. We were living vicariously. We had to meet in person to talk about it and ask them questions. Then we used the spokescouncil model used at Seattle to organize A16, pretty much right afterwards.

R. Harvey: I was like 15 years old, I couldn’t go out to Seattle. After that, like many, that day, I was on the internet reading about globalization. During the WTO in Seattle, I remember reading Indymedia, I remember the Global Exchange website—they had a good set of Fact Sheets.

Mimas: We were successful in disrupting the WTO ministerial by stopping delegates from actually attending the meetings through massive street blockades, which were met with tear gas, billy clubs, and general violence from the police.

The street protests led to the emboldenment of African, Asian, and South American countries within the WTO meeting itself and effectively scuttled the progress of the talks which were heavily weighted for richer countries against the poor. It wasn’t a total victory—capitalism was not completely derailed that day—but it was much more than anyone could have expected.

Seattle was perfect in lighting a match—all our different projects now had an umbrella to live under. It would start with capitalism and the exploitation of the Global South, but it also fit later with the first George W. Bush Inauguration, the Democratic and Republican Conventions in 2000, and even the anti-war movements after 9/11. Later on, I think you can make an explicit connection to Occupy and an indirect connection to Black Lives Matter, as well. There was a broad understanding that you could wear multiple hats, be a part of different movements in solidarity.

Mark: There was the whole plan, the whole ring to block off the intersections, to stop the delegates from attending the ministerial. Initially, that morning, we were like “OK, things are calm,” nothing was really happening. We went back around the convention center and it was a full on shitshow, it was massive, riot cops with tanks and tear gas canisters—all the images that you’ve seen—a war zone.

And they’re pepper spraying—these battles of pepper spray—so we stayed in the street for a while. We got to the Indymedia center with all this footage, and we were trying to get it downloaded so we could get it in the broadcast, trying to get it edited—we edited it all night, I didn’t sleep for two days. Or three?

I remember going into the Indymedia center and being like, “Oh my god, it’s a riot.” And Eric Galatas, who’s a Free Speech TV guy, Indymedia guy, one of the founders of Indymedia, said “No, it’s an uprising. Let’s be clear.”

https://twitter.com/crimethinc/status/1200763806898626560

Taking on the IMF and World Bank

With Seattle setting the template, the next target was five months later in Washington, DC: the meetings of the IMF and World Bank in April 2000.

Ryan: A16 was already being planned prior to Seattle, but the meeting and the planning for it increased exponentially after Seattle and showed that the movement was on a new trajectory.

The Mobilization for Global Justice was a broad coalition that was anchored by three different categories of organizers. First, any activist who was interested off the street. Second were Unions. Third was international NGOs like 50 Years is Enough and Jubilee 2000, key NGOs working on debt relief in the Global South. Public Citizen had a presence in Seattle and also was involved with A16. This coalition was made up of dozens of smaller DC activist groups. It was a smorgasbord: DIY punk activists like my group of friends and many people who worked at NGOs but wanted to be part of something bigger.

Lelia: I really remember Nadine Bloch being central in the DC organizing for A16, because she could say, “This is how it was done in Seattle, and this is what might be done here.” So we went from there, it felt both that we had some semblance of organization but it was still organic. It felt good. I was part of the spokescouncil meetings, plus the Infoshop folks, plus being part of the American University crew, so I don’t exactly remember what hat I was wearing at a given meeting.

Mimas: A16 wasn’t just a single day. It was really a week of resistance culminating on April 16 and a few days after. People were there for over a week before that date itself. A16 was one of a series of global Days of Action against international capitalist entities, which included the first Carnival Against Capitalism the year before in June and, of course, the Seattle protests.

What you need to remember is that these Days of Actions were in direct response to calls for international solidarity by the Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico. The Zapatistas were so damn cool; they were both completely inspiring but, how can I say this politely, also sort of too good to be true! Balaclava’d revolutionaries in the Mexican jungle talking about international resistance to NAFTA and neoliberalism? That definitely captured our full attention.

As it turned out, the Zapatistas were the real deal. They were extremely important because they initiated a number of international meetings of activists, called encuentros, first in Chiapas in the jungle, then in Spain and Geneva, between ’96 and ’98. By getting all of these activists together, they helped to develop space for an international movement. By the time it came for Washington DC, A16 was just another link in the chain. The World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, NAFTA, the FTAA—we saw them as a part of a coherent system that needed to be resisted.

Panagioti: I remember a lot of trying to replicate what we saw other people doing in Seattle, people having a lot more experience than I had. I guess I’d gone to some Ruckus Society camps by that point; I volunteered at the kitchens. I don’t think I was climbing yet, Ruckus direct action climbing was a lot tighter than Earth First!’s. I think they’ve shored up those gaps in recent years.

We were trying to figure out how, with limited experience and resources, to plug in and do the technical stuff, blockades, the structure of who makes calls. We were deciding pretty intensive shit, like, how many lockboxes do we need to build? Who’s going to put their arms in them?

I had just learned how to do these things myself—blockades, sleeping dragons, tripods—and now I was training hundreds of people how to do it. The experience we had in Seattle was formative enough that we thought, “We could just train everybody else, back on the East Coast.”

Pica: I mostly understood the whole dropout thing, they were poor and squatted and trainhopped, they were dedicated to radical change. One thing that bothered me at the time was the whole “professional activist” thing. Maybe it was my naïveté, but the idea of someone getting a paycheck from some official reformist group to organize protests was somewhat of a contradiction to me. Today, I understand it, everyone has to make a living; but at the time, I thought it had to just be about passion while you did your crappy day job and hustled on the side through grassroots activism.

These people seemed to have unlimited money and I really wondered where it came from, but maybe that was just my class war mentality coming through. Bless them for dedicating themselves to the cause, but if it comes with strings? If you are condescending? No way. Don’t lecture me about non-violence or alienating “normal people” if you’ve never held down a minimum wage job, you’re the one who is alienating us!

Ryan: A certain amount of organizing locally had already occurred six to nine months out, and then, around the three month mark, someone would pay those people money to come in, they’d live in DC temporarily. They acted like hotshots, they were often slick glad-handers.

These people and the funders, they want things to be set up in a certain way. “We want to move everything to look like this.” Our little crew of activists would go to Mobilization for Global Justice meetings, but for the most part we never felt welcome there. Most of the meetings we went to in DC, prior to A16, were majority people of color. That was something new with the anti-globalization movement, there being more white organizers and upper-class people involved in DC organizing.

The Mobilization for Global Justice, at least on the surface and its professed approach, was a consensus-based organization. If you dig a little deeper and you understand the politics that were at play and where the money was coming from, the people who were the swoopers, there were definitely problems regarding who had power and who was given more say.

Panagioti: We organized really hard in Florida, coming back from Seattle after a few months of traveling. I was doing Earth First! a lot at the time, the first convergences, fusing those experiences. We did trainings for a few hundred people around the state, at a bunch of cities and conferences, and talked about the blockades in Seattle and our organizing there. From the blockades to jail solidarity to the follow-up anti-repression work that happened and the lawsuits that followed.

We had a glimpse of that vision by the time the convergence in Washington, DC was called for. A lot of people who I still know today, I met at those trainings. The people who started the Miami Workers’ Center and the Coalition of Immokolee Workers, some of those people who were building their local or statewide projects around the same time period, we were communicating and organizing together. The idea was we were doing these trainings to put together these street blockades in DC.

Sand: At 4 am, in the days prior to A16, we whizzed through DC to re-wrap the front page of 20,000 _Washington Post_s with a mobilization parody on the IMF.

Stop signs, mailboxes, streetlights, bus stops, and other features of the urban environment expressed solidarity with the protests.

Ryan: All the NGOs wanted to be connected to A16 organizing, environmental groups to animal rights to social justice. Everybody wanted to find a place for themselves and find themselves involved in the A16 organizing.

And there were the unions. The unions brought a lot of money, a certain amount of budget and certain restrictions on what things would look like. Then there were folks like the Direct Action Network, from Seattle, Rainforest Action Network, people connected to Ruckus.

Ben: There was a ton of planning for RTS—too much, really. There was a cool kids club, who’d go to the spokescouncil meetings for the Direct Action Network, so it became a bit of a high school thing, a little ageist. If you were a teacher, maybe you were made to feel that you didn’t fit in. There was some sexism in the meetings, some people talked too much, a lot of the males. And queer people weren’t as always welcomed in the meetings. You professed it, but if you are always dominating, you’re not really making space.

Panagioti: I had mostly positive associations with the feeling of dispersed decision-making and collective process, but I’m also quite certain that if I were able to give it more thought and dig a little deeper, there were certain personalities who drove a lot of it as well.

Ryan: They were of a particular generation, a particular age. We always called them the helicopter activists, we also called them the swoopers. They were often from California, more “progressive” places and were inclined toward imposing their culture and ways of working.

Mark: I was already both feet into the deep end, the next year or two after Seattle, the movement such as it was really was my life for those years. It probably already was, but now even more so.

Lelia: We were friends with Adam, we did a lot of wheatpasting. He organized these paid wheatpasting nights, with these beautiful posters for A16. Someone gave us money to wheatpaste!

Jimmy: I was bummed I missed Seattle, but I was glued to TV news coverage, anything I could glean off the internet, newspaper articles, clippings. The reportbacks were a huge thing, really galvanizing. People were like, OK, what’s next? A16, here we come.

Vikki: One of the things that came out of Seattle was this story of a pregnant woman who got tear-gassed, and she miscarried. I remember that people had criticized her for being there and then it turned out she was just going to get groceries, or whatever. And I thought “Why are the cops going around teargassing pregnant women? What the hell’s wrong with them?”

Literally that afternoon, as we were heading down for A16, I was getting ready to get in the van and I was packing up my stuff. I hadn’t gotten my period for a while, which wasn’t something I normally tracked too closely. With that woman’s story in mind, I thought, well, maybe I should go get a pregnancy test. I’m sure it will be negative, I’m sure it’s because I haven’t been eating well. We had been working on opening a new building to squat, near the Adam Purple Squat on Forsyth Street, and I was sleeping there. I figured I just hadn’t been taking care of my body; this is probably why I’m late.

I got the pregnancy test and I peed on the stupid thing and I’m waiting, and I’m trying to figure what to pack in my bag, should I bring a big blanket or sleeping bag, you know, what would be best for this weekend trip? And then I looked down at the pregnancy test; and it was positive. OK, wow.

So I called my partner. And he picked up the phone, this was back in the day before cell phones and luckily he was home. So I called him and I told him I was going to DC for the weekend and he told me to have fun and I said “Oh by the way, I’m pregnant, so if I don’t get tear gassed and miscarry, we should have a conversation when I come back.” You know? “I’ve got to catch this van,” and I hung up the phone and left.

I told two people on the van ride, in case something happened to me, in case I started bleeding. You wanted people to know what was happening if you’re having a miscarriage on the street. When I got to DC, there was a communal kitchen. I ran into an old roommate who was there and told them, and they started talking about how it wasn’t known what the long-term consequences are if you get tear-gassed and you don’t miscarry. She was explaining that we don’t know what happens, if I chose to keep it, to your later baby if you inhale a shit-ton of tear gas. And I hadn’t thought about that. My plan was to run with the black bloc and go fuck shit up.

After that conversation, I decided I wasn’t going to go to the black bloc. Someone mentioned there was a legal protest planned. I figured that sounded boring; I could have just stayed home if I wanted to go to a legal protest. Why come all the way to DC and sleep on the fucking floor just to go to a legal protest? I wound up joining the Food Not Bombs flying brigade, we made food, put it in a shopping cart, and fed people all weekend out on the streets.

My daughter isn’t impressed by this story, by the way, she doesn’t really care! I think she turned out fine.

Black bloc demonstrators in Washington, DC on April 16, 2000. Photograph by Orin Langelle / Global Justice Ecology Project.

Hitting the Ground Running

A major mobilization demands months of logistical organizing. It means setting up a convergence center, legal support teams, street medics, houses for dozens of people to crash, kitchens to provide free food to thousands, and Independent Media Centers for activist journalism. It involves building giant puppets, forming brass bands, planning for creative resistance such as banner drops and direct action.

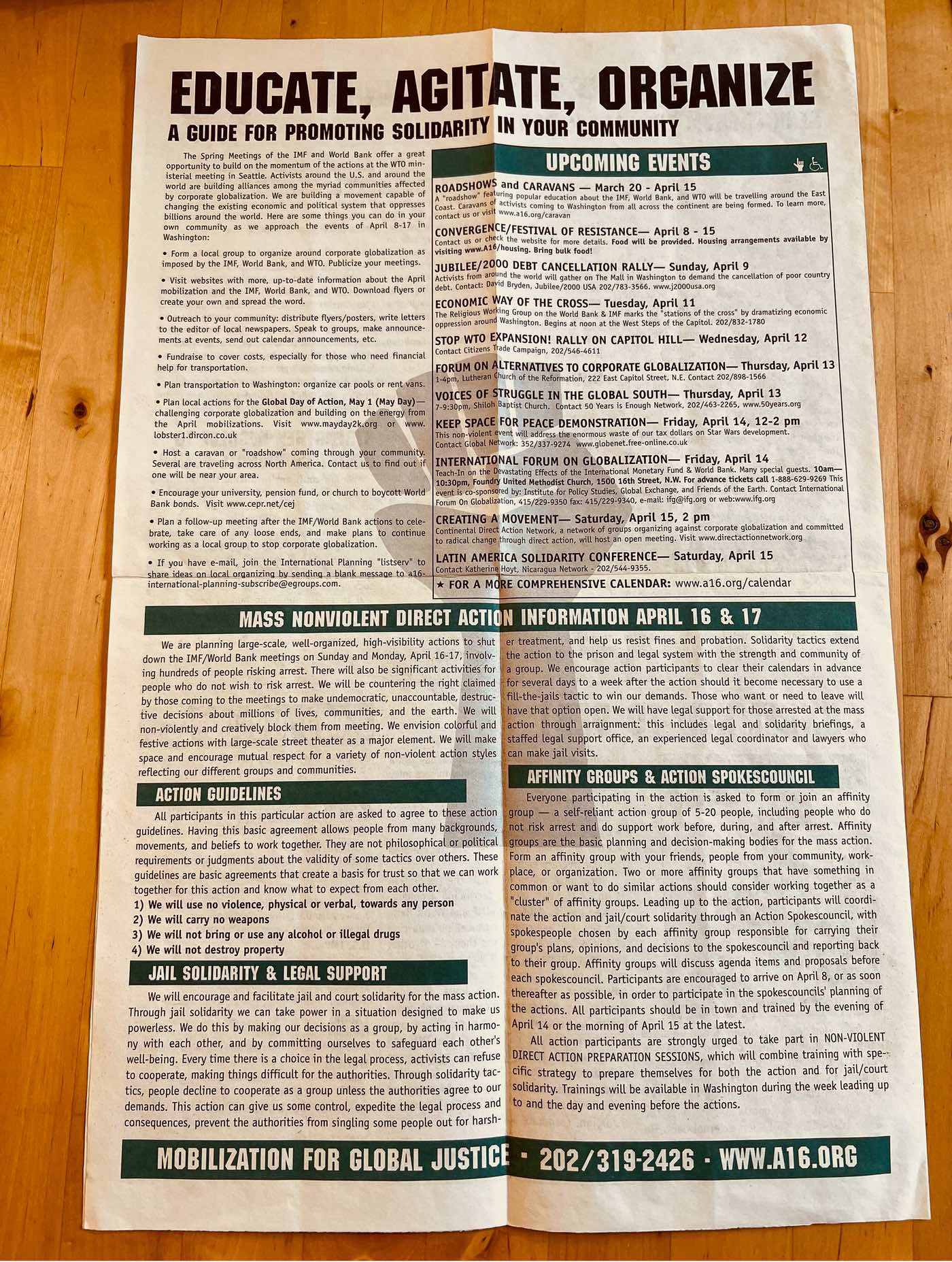

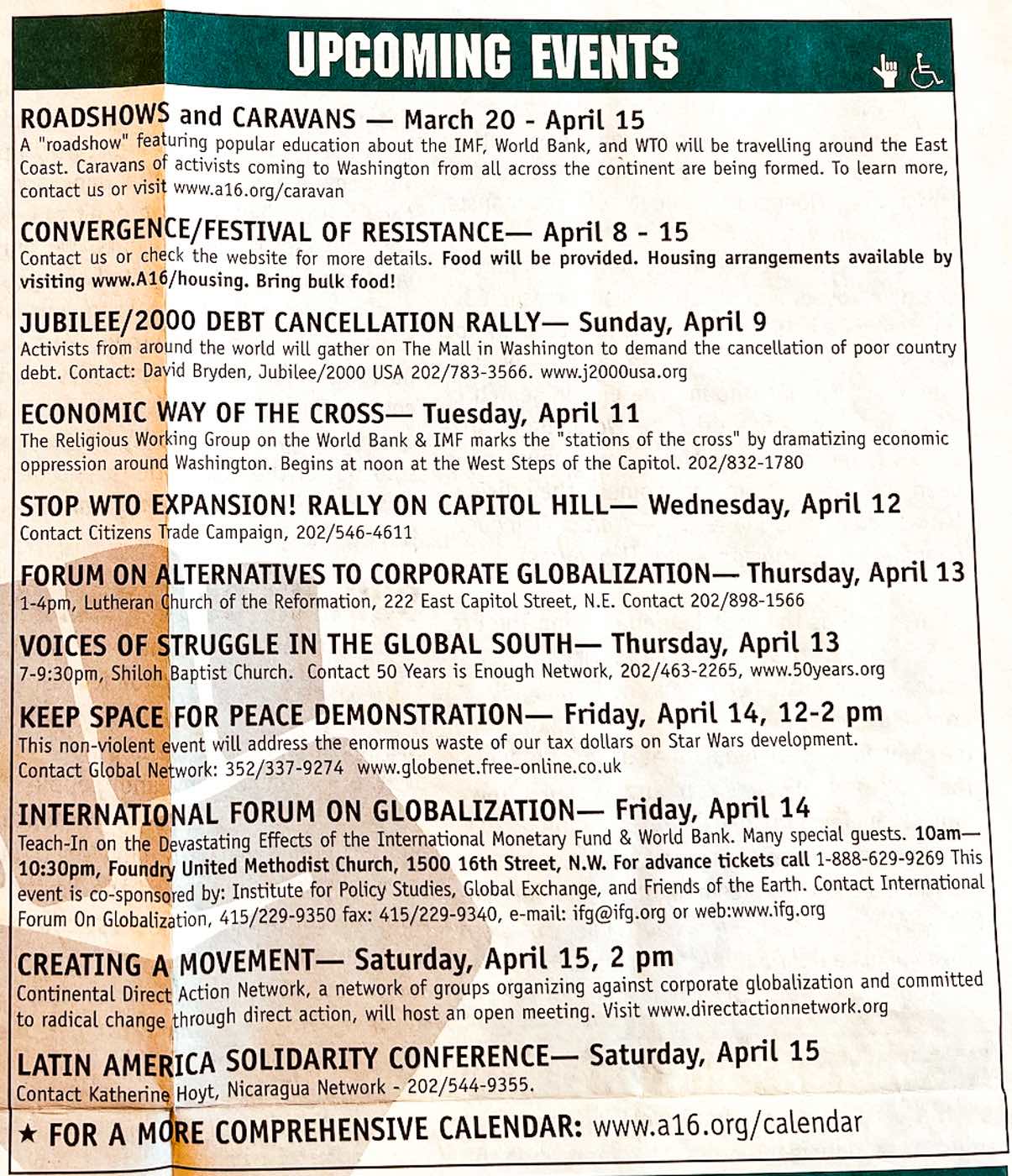

The Mobilization for Global Justice produced a pamphlet including a calendar of events for the protests and explaining why demonstrators were resisting the IMF and World Bank.

Sand: The check-in hall at the convergence center was flooded with information and help. You could buy a T-shirt, find out when the next training was, or post a notice for a friend. There was a whole garage area for making the large puppets usually with about 20 busy bees hammering, painting, and papier-mâché-ing. You could just stand there and soak up empowerment.

Mark: We had shark fin hats, and polyester leisure suits that we got famously from Harry Bubbins at Casa Del Sol, which we traded him in exchange for a canoe. He had like 400 of these polyester leisure suits, blue, who knows why the fuck he had them, but they were perfect for us. He said “I’ll give them to you for free, but I need a canoe.” Which we did!

We had all had our gear at the Reclaim the Streets crew and we wound up sleeping on the floor of one of those churches you wind up sleeping in. We had a van. We were rolling with the Hungry March Band, they were our soundtrack. So, HMB and RTS, we were wedded and it was a blast. We were a roving cluster, we didn’t lock down, the whole idea of trying to shut down the meetings didn’t materialize.

Many of us have come from Asia to be with you today. We did not come to dialogue with the World Bank and IMF. We did not come to negotiate. We actually came to shut down these institutions.

-Walden Bello, Filipino Activist, Focus on the Global South

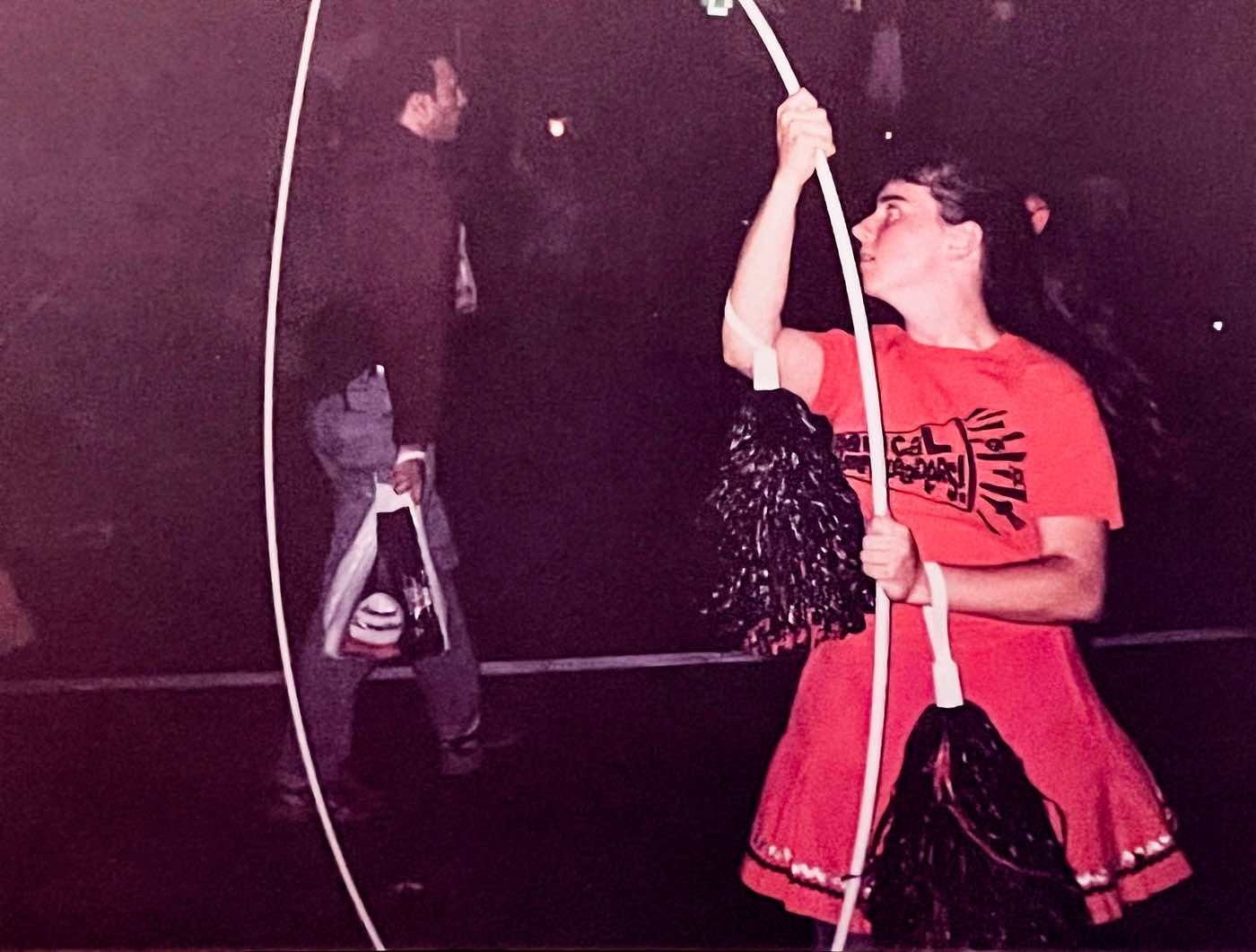

Sand: I loved making cheers, skirts, and pom-poms: rounding up Radical Cheerleading squads. We did cheers in metros, restaurants, department stores, and at Farragut circle for 30 cops parked on their bikes (you know they loved us).

Throughout the week prior to A16 itself, you could go to a ton of other political actions: a banner drop attempt on Monday, Iraq sanctions lobbying, a Free Chiapas rally, the day action for Iraq, a Global Network rally against nukes in space, School of the Americas lobbying and fast, Jubilee 2000, and rally against the Prison Industrial complex. I never even had time to go out for Ethiopian food! On Saturday, we sent surprise press releases and at least 100 media outlets came to Dupont circle for our huge street performance.

Radical cheerleaders in Washington, DC for the mobilization.

Lelia: I was at the mass arrest on A15, at the Prisons rally. I was in college and I had a final or something so I couldn’t miss class; I dodged through an alley, out a parking lot, and managed not to get arrested. All my friends got arrested. It was a large open space, they had cornered us and corralled everyone by blocking off the streets.

Mark: For A16, I wore both hats fully, Paper Tiger TV and Reclaim the Streets, so I was involved in bringing online the second Indymedia iteration, which Eddie Becker was involved with and DeeDee Halleck and Michael Eisenmenger, all these amazing people. And Rick Rowley and Jackie Soohen from Big Noise films, who were amazing.

A lot of the same players from Indymedia Seattle were in place and I was at those meetings trying to figure all that out and figure out what my role would be.

Michael: On Saturday, April 15, the police shut down the protesters’ Convergence Center under the pretext of fire code violations. To paraphrase DC Police Chief Charles Ramsey’s explanation, this was done because he cared about the demonstrators’ safety. The 1350 arrests, the tear gas and pepper spray, the beatings, the denial of legal and human rights to those arrested, the intimidation, surveillance and sabotage must have been Ramsey’s version of “tough love.”

Police on one side, puppets on the other. Iconic art from squatter artist Fly referencing the police raid on the convergence center in DC.

Sand: The decision by the DC police to shut down the space on A15 was very strategic. It was a big blow, but some were surprised it lasted as long as it did. However, we had back-up sites available immediately.

Ryan: There was a black bloc spokescouncil meeting the night before A16, there were maybe a couple of hundred people in that room. We had it at the Wilson Center, the same place we had many punk benefit shows at the time. The strategy discussed was that the black bloc would act as a flying squad to support the lockdowns in place to close off access to the IMF and World Bank meetings. On A16, the bloc really acted as a solidarity squad.

There was a comms team—you know, “Police are cracking down at this intersection,” then we’d go there to give support and the bloc would roam around and help out wherever needed. It was very much under diversity of tactics, people had other plans to do this or that. The thinking was: we’re going to show solidarity to a certain set of values, we’re going to make anarchism and anti-authoritarianism visible and be a self-defense group for those who are locking down, to try to take some pressure off them.

There was a conversation around the topic: we’ve been stigmatized as the troublemakers after Seattle; so what’s the best way to show up? We’re here in solidarity, so when the police are cracking down on other activists or other tactics, we’re here to show we back up everyone.

Gabby: I cut class to go to A16, I was still in high school and I had decided I was going to these protests. I was too young to go to Seattle, it was too far away, so I was really a kid when Seattle happened. DC was close enough, I don’t know how I got there, whether it was a Chinatown bus, or a school bus running on grease, a grease bus that a lot of people jumped on. I didn’t really have any friends with cars at that point.

R. Harvey: I only went down on the day of the 16th, we got there at 9 in the morning, maybe. I remember driving in and having the feeling that this was a big thing, driving into the city. We stopped at a gas station, and there was a person coming into the station as well, and they’d just gotten out of jail, arrested the day before. I remember that was the first thing, we were just on the outskirts of the city and we meet someone who had just gotten out of jail. We were like—this is going to be big!

Demonstrators blockade an intersection in downtown Washington, DC with lock boxes on April 16, 2000. Photograph by Orin Langelle / Global Justice Ecology Project.

A16: All Together

A16 itself was on a Sunday. By the weekend, there were already 20,000+ activists from across the country plugging into a myriad of events, protests, rallies, marches, speak-ins, and direct actions.

A calendar of events in DC in April 2000, produced by the Mobilization for Global Justice.

Lelia: I started the radical cheerleaders squad in DC, so I remember going down to our set intersection. I think we were between H and I on 16th street. I remember people planning on having the adult diapers, but when it came time to do it, people were like “I’m not actually doing that.” I was like, “This is serious! We’re not leaving this spot!” We linked arms for that intersection, we kept the crowd engaged and entertained with the radical cheerleading.

Jimmy: I remember getting up at 4 o’clock in the morning and walking through the darkness, at some point meeting up with friends who had cell phones, they were the comms people. Oh, wow, these were tiny little things, not the yuppie cell phones from the ’80s anymore.

The crowded streets of Washington, DC on April 16, 2000.

Nicole: We had a small group of people who got in cars really early in the morning to go to Washington. We came with all this stuff in case we got pepper-sprayed, in case we got tear-gassed, handkerchiefs, vinegar, all that, and we’d wear glasses instead of contacts.

I wound up leaving the people I went there with—some of the people I went with were locking down with a Sweatshops event. A16 was such a huge thing, you could come at it from an environmental lens, or via American neocolonialism. Or it could be from a labor perspective, whether in the US or elsewhere. You could come at it from a variety of perspectives, or in solidarity with developing nations and people directly fighting neoliberalism.

Jimmy: I will always remember that image of Panagioti stepping into the intersection at 5 in the morning; sticking his hand out at our assigned intersection for our blockade, and the car that would have been passing through just stopped. Then it reversed, it backed up as the cluster moved into place. I thought “Shit! We’re doing this!”

Protesters blockade the streets of Washington, DC on April 16, 2000.

Panagioti: People were really determined not to get the shit kicked out of us again, so they brought extra padding, plus the football pants and the crazy homemade gas masks. Kip had this amazing body armor. We had gotten arrested together in Seattle. People rode freight trains across the country with a bag full of whatever materials they needed to protect themselves.

There is good news coming out of the US when the youth of America rise up and take to the streets. I challenge you to rock the boat on Sunday!

Ryan: Some of those affinity groups wanted to be in the black bloc, some wanted to do lockdowns, some only wanted to go to the rally. In those days, in my 20-year-old mind, I may have been a little judgmental—“So you just want to go to the legal rally?” But in the end, they were our friends, we supported them and they weren’t necessarily arrestable. We are all working through a lot. We were questioning a lot of assumptions within ourselves and trying to figure out where we fit into this exciting movement.

Nicole: Early in the morning, the goal was to block traffic, to stop people from getting to the IMF meetings. I don’t know if that was successful, but I saw the lockdowns in the morning. There was tear gas, people running, people locking down, the cops coming.

By daybreak on April 16, nearly every intersection in downtown DC hosted a lockdown, street party, or demonstration.

Ben: For the IMF, my favorite bit of street theater was the “Twelve Days of Monsanto.” We were singing Christmas carols for all of the joyous aspects of Monsanto. Our flying squad was great. We’d sing “Mack the Knife” as loan sharks, with a kick line, and that kind of worked. I had a sense that we wouldn’t be able to block the entrances the way they did in Seattle, that just wasn’t going to happen.

But I thought the message was powerful: If you wanted to get lifesaving drugs into bodies around the world, you had to address the IMF’s structural adjustment and austerity programs. The debt that was strangling governments like Haiti’s from being able to create their own health care programs. There were these groups like Partners in Health for Haiti, and Health Gap that were coming up, saying, “We can do better than this.”

That was the moment right before Seattle that Al Gore was saying he would defend the drug companies—when they were in the process of suing Nelson Mandela! Now that’s tacky. Here’s the global non-violence hero of the century [sic],1 and you’re suing him for trying to make life-saving drugs for South Africa.

Mark: Entertaining the troops was the mission, going to the people who were locked down for 15 hours and do a little routine for them and then move on. We got to see such a mix of people, young, old, Black, white, Brown, so many people; it was polyglot. That one in particular was very diverse. It was very multi-generational, multi-class, multi-racial, all together.

Panagioti: Part of our team, someone who’s now a lawyer in Oregon, was part of the comms team. We had handheld radios. I was in proximity with the people who were in more rigid responsibilities, I was like a block away breathing fire during the street theater performance. There are photos somewhere of me and —— breathing fire in the street.

Lelia: There were delegates trying to get in, in a convoy, and the police trying to clear the intersection. I will never forget this to this day—we rushed from our separate lines, blocking the sidewalk, and rushed into the intersection. We sat down, we linked arms and there was a huge—it felt like a tank—but maybe just a very large police vehicle. All these guys jumped out with their SWAT gear. And they hit every other person who was locked down on the bridge of their nose. Every other person had a busted, bloody nose.

I’d seen police violence previously, and I’m familiar with police violence that was worse than this, but I’d never before seen police walk into a crowd of people and slug people like that. Just with abandon. I’ve never looked at police the same way, I’ve always looked at them with distrust, but I couldn’t have imagined that they took their billy clubs and hit every other person across the nose, one by one.

I remember it. Luckily, I was not one of the people who got my nose smashed, but tending to those people—it was really nuts. They tried everything to get us to move.

The black bloc came at that moment when blood was streaming down people’s faces and essentially pushed the police out of our intersection. They were just this wall of bodies that pushed them out and saved our intersection from any further police abuse. I’ve forever been grateful to that black bloc for hearing on the walkie talkies that we needed help and coming so powerfully to our aid.

Mark: The black bloc was in full effect. They were very militantly opposing police aggression and defending protesters, that’s how I would put it. They were picking up whole chain-link fences and charging police lines, you know, forcing the police back on their heels.

Since I was with a roving cluster, we experienced some of that, but we tried to steer clear of the most intense stuff. But you know, we inevitably saw it all, we were roving around all day. It was exhausting but exhilarating. And then that night, I went back and edited video for the Indymedia broadcast.

Clashes in Washington, DC during A16.

Michael: I was at K and 18th St. when, unprovoked, police fired tear gas and went on a rampage, clubbing demonstrators as they tried to get away. Eventually, the intersection was completely militarized, with over 100 police, the National Guard, and a small tank securing the area. Elsewhere, tear gas, pepper spray, and clubs were being used liberally on nonviolent demonstrators.

Joe: All of us who went to Washington, DC for the A16 protest have an obligation to represent to others what we went through. It’s not often that human behavior can lead to such massive power and chaos all at once. To challenge authority so greatly that it fights back, reveals its tactics and weaponry, just as we are revealing our strengths and tendencies in stating our demands, in massing and marching. That characterized A16.

Lelia: There was so much energy. I worked on a large puppet, I did a bunch of puppets over the years. We did a Critical Mass ride as well, the police motorcycles started running into us. My partner got arrested in that. I remember the moment they were handcuffed, it was crazy watching them get arrested for riding a bicycle. Getting arrested for attending a normal rally.

A giant puppet depicting a pig with the world in its mouth like an apple, representing the IMF, appeared in DC in the early hours of April 16, 2000, as protesters got in position to establish blockades.

R. Harvey: It was exhilarating, it felt like something was happening. We were there to disrupt the meeting. If you’re doing something to disrupt the meeting, then it’s effective. The thinner spread the cops are, the less quickly they can arrest the people who are locked down.

Diversity of Tactics: Marching Bands, Blockades, Flying Squads, and Radical Cheerleaders

People came to DC with a wide array of visions regarding what A16 was about and a wide range of tactics and strategies with which to do their part.