In 2019, militants in Austin, Texas started an organization with the aim of defending homeless camps against sweeps—forced removals disguised as “cleanups” carried out by cops and work crews. This organization, Stop the Sweeps, intervened in a cycle of struggles that included the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the George Floyd uprising, and the winter storm of 2021 while attempting to consolidate a pole for confrontational activity and strategic thinking. Here, we explore the history of this movement in detail, seeking to distill lessons about autonomous organization that can aid revolutionaries in future struggles against dispossession.

In June 2019, Austin City Council passed a reform legalizing “camping,” taking away the tool of misdemeanor ticketing from the Austin Police Department, which had used it for two decades to push homeless encampments into the deep woods and routinely dispossess the residents. The NGO left promoted this as a dramatic advance in the civil rights of houseless people, while NextDoor reactionaries decried it as a sign of the debasement of the once great city of Austin. In the news and on Twitter, Texas’s Republican Governor Greg Abbott exchanged barbs with Democratic Austin Mayor Steve Adler, each taking one of these sides.

The following November, friends and comrades formed Stop the Sweeps Austin (STS), a political intervention intended to undermine both of those positions. The core aim of STS was to show that both the progressive city and the reactionary state used similar techniques, rationales, and low-wage contractors guarded by police to systematically dispossess the poorest and most marginalized people in Austin—and that in doing so, they were continuing policies of displacement that had begun more than a century earlier with colonization and the policing of enslaved and formerly enslaved populations. Confronting the sweeps was both materially and discursively strategic. The idea was to cut away at the foundation of the post-decriminalization strategy for displacement, heightening antagonism towards both of the political factions that depended upon it.

To do this, Stop the Sweeps Austin rallied sympathizers to intervene against weekly encampment sweeps by city and state forces while building parallel networks of mutual aid and political support. STS drew on existing solidarity networks descended from decades-running projects, informed by the living memory of the social movements of the homeless in the 1980s. We also benefitted from historical research and movement elder storytelling to extend our understanding of local history to the founding of Austin.

The sweeps are intended to destroy what little stability and sense of home the houseless are able to establish.

We now recognize that we were a part of a national movement against sweeps that peaked early in the COVID-19 pandemic, drawing on the momentum of the George Floyd Uprising. Autonomous groups in California, including the Sacramento Homeless Union and Where Do We Go in Berkeley, had been organizing against sweeps through 2019. In an early phase of STS organizing, we were roped into coalition building and national legal work by the Western Regional Advocacy Project; yet these projects did not offer meaningful coordination between groups to advance an autonomous vision grounded in direct action. There were efforts in Los Angeles to build out anti-sweep programs that seemed similar to ours from afar, though they started from a stronger orientation towards social democratic city politics. Fiercer resistance in Minneapolis built to flashpoints in 2020 including the occupation of an empty hotel and militant encampment defense. The circulation of the insurrectionary framework “You Sweep, We Strike” saw attacks on contractors and city infrastructure in Seattle, Santa Cruz, and Minneapolis. It was difficult to connect with these projects to learn from them directly, but easy to boost each other’s content from afar.

Five years after the founding of Stop the Sweeps Austin and two years after its quiet dissolution, we are writing this piece in hopes of refining the lessons of this recent high point of movement activity. We will begin by painting a picture of the moment in 2019 when Stop the Sweeps emerged, then situate that moment in a longer history of colonization, development, and homeless resistance. Having done so, we will distill the strategic frameworks that guided our organizing, then follow the trajectory of the movement to the limits it encountered. In each section, we will present our hypotheses and the lessons we learned along the way, illustrated via specific practical experiences.

We offer these as reflections both for the local movement—to remind it of its history, its victories and defeats—and for revolutionaries everywhere seeking to think through crucial questions about autonomous organization. Today, we are preparing to confront a new phase of camp repression in the wake of the Supreme Court’s “Grants Pass” decision, which green-lights criminalization and displacement in California and elsewhere.

A sign on a tent in downtown Austin.

1000 Tents Bloom

Before 2019, most encampments lasted about three months before police evicted them—a cycle of temporary inhabitation and dispersal. This constant motion is essential to the cycle of development, as it opens up land and keeps bodies moving through the various infrastructures built to profit on them—shelters, social services, housing, prisons, hotels, and stores, all of which increasingly resemble each other.

Though “camping” was formally legalized in June 2019, enforcement had actually ceased during the winter of 2018-2019. Citing a paucity of funds due to the consequences of the catastrophic Hurricane Harvey in southeast Texas, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) paused its contracts providing camp removal, attempting to hand them off to the City of Austin. The city government did not immediately pick up the contracts at the same pace. At the same time, informal directives were given to APD to slow the pace at which they inflicted tickets for camping, fearing court rulings enforcing an expansion of the Martin v. Boise circuit court ruling, which had slowed camping ban enforcement on the West Coast. This occurred alongside a soft strike by organized Austin Police officers who had significantly slowed their response times to minor crimes, aiming thereby to press their demands for more power.

The repeal of the camping ban created a political opening, enabling the camps to survive indefinitely on public land. Tent cities blossomed in January and February, mainly under state-owned freeways, and grew more elaborate. Shanty towns and shelters made from wooden pallets, political signs, and tarps as well as more modest tents and cardboard populated the city north to south and east to west, dotting the parks and the underpasses of major highways and appearing beside libraries and around the social services buildings downtown. This offered new forms of collective stability and security for the unhoused: the camps served as points of connection, stable locations at which to receive social services, and places for those new to life on the streets to get oriented and find support. They represented a strategy for mutual safety against harassment by reactionaries and police, providing a sense of collective life and care.

An encampment below the I-35 overpass in the heart of downtown Austin.

This occupation of space shocked liberals and conservatives alike, many of whom saw it as a display of public disorder or an embodiment of the ever-intensifying crisis in affordable housing. In Stop the Sweeps, for our part, we saw the expansion of the camps as a sign of the self-organizing capacity of the homeless and a demonstration of the power of land occupation—indeed, a signal of disorder for those invested in the property system. STS sought to build connections centering this sense of self-organization to build a defense network against the waves of displacement that were the cause and consequence of life in the camps.

At that time, the displacement of the housed poor had continued unabated across Austin for decades, in keeping with national trends and local plans to develop and gentrify first West Austin and then East Austin, which was historically home to Black and brown Austinites following a century of segregation. Recent statistics show that most homeless Austinites were displaced from the zip codes that they currently reside in, often in areas suffering intense gentrification. While most recent literature on rising rents in Austin focuses on the spike following the pandemic, money had been pouring into Austin neighborhoods long before that, aided by historically low interest rates intended to flip houses and entire blocks into money makers. Projects that had been paused since the previous real estate bubble burst in 2008 were resumed during the 2010s with towers and “luxury” apartment blocks mushrooming from the mycelial networks of capital and property that had accumulated and expanded during the “bust” period.

In the late 2010s, the local Maoist movement (now mostly disbanded and critiqued as a cult by former members) waged a years-long struggle against a development slated along East Riverside, an effort to reinvent a low-income area as a luxury new-urbanist hotspot: the Domain on Riverside. The developers ultimately succeeded in evicting low-income renters from multiple high-density apartment complexes, which consequently remained boarded up for years just a short walk away from one of the largest encampments on that avenue.

These Maoists represented a political pole in 2019 Austin, offering a mixture of public and secretive activity that prioritized direct action and confrontation with a diffuse array of enemies that they saw as aligned with the interests of capital. On the one hand, this meant that developers were confronted in public meetings and at their homes, and on the other, that former allies were castigated online and in person after political breaks. The Maoists also confronted other minor political figures, including DSA-oriented candidates, and disrupted their meetings. At the time, the Maoists had developed a reputation for being arrested, both at marches and in their homes, and facing elevated charges. Their former leader, Jared Roark, who went by the name Dallas, was arrested in his home for weapons possession after a tragicomic confrontation with an expelled former member of the Maoist’s armed unit.

The DSA and an array of activist non-profits oriented towards electoral and council-level reforms represented another pole of activity. While less active in the streets, this alliance fused respectable political activity—rallies, press conferences, and testimony at City Council—with flirtations with abolitionist frameworks. The Homes Not Handcuffs coalition emerged out of this scene; they won the 2019 camping ban rollback, spawned the autonomous mutual aid organization Street Forum, and recomposed briefly to defend the camping ban at the polls in 2021. Their organizing relied heavily on personal relationships with City Council “progressive” heavyweight and current Texas Representative Greg Casar and on a progressive political machine comprised of organizations like Grassroots Leadership and Workers Defense Project, which had won reforms at similar scales through the City Council in the 2010s.

STS oriented ourselves by drawing from political traditions and organizations that overlapped with these but were distinct from them. Many of the initial organizers were drawn from the local anarchist milieu, which had been working to draw links between different tendencies and organizations. One was the Peaceful Streets Project, which had emerged from right libertarian circles amidst the Occupy Wall Street cycle at the end of 2011, but had split left in the course of a decade of anti-police struggle. PSP served as the local Copwatch, filming police interactions and developing an aggressive interventionist style in which they named and shamed local cops, occasionally becoming personally known to the police themselves.

Another influence were members of the Autonomous Student Network, who had cut their teeth organizing at the University of Texas and had gone on to participate in the Peaceful Streets Project and the Occupy ICE movement that established an occupation outside a detention center in San Antonio; they also helped to start Street Forum. These organizers brought an experimental streak to organizing, with a willingness to take risks and say what only anarchists can say.

Contributing historical memory and serving an organic link to Austin’s homeless movement were members of The Challenger Street Newspaper, also born in 2011 out of the ashes of The Advocate, a long-running more traditionally NGO-style paper. From its beginnings, The Challenger was smaller and scrappier than the Advocate, with more will to participate politically in social movements. The Challenger published monthly issues with articles written mainly by homeless people in Austin, focusing on life on the streets of Austin, political commentary, poetry, and art. The Challenger had resuscitated the memory of Homer the Homeless Goose, the mascot of the Street People’s Advisory Council—a direct action organization of homeless Austinites in the 1980s who led occupations of vacant buildings and, famously, the downtown lake.

Along with contributions from other early members involved in anti-prison struggles and the Libertarian Socialist Caucus of the DSA (which was focused on mutual aid), these organizations helped build the political framework that STS used as we attempted to build an alternative pole, intervening in the fight to defend the camps. This enabled us to synthesize tactics and strategic insights from a variety of experiences. Coupled with insatiable demands and a hostile attitude to the state, that equipped us to punch above our weight.

The shelters were full.

A History of Displacement and Contestation

Now that we have set the stage in 2019, let’s back up to explore the history of homelessness in Austin and the movements combating it.

The City of Austin was established as a military maneuver intended to project burgeoning Anglophone power westward after Texan independence from Mexico in 1836. Settlers established a semicircle of forts to the west to defend the new capital from raiding Comanches and other Indigenous people. Austin’s famed Barton Springs are part of a chain of springs in Central Texas that had been in continuous use by Indigenous peoples for over 10,000 years; they appear in some Texas rock art. Military campaigns and raiding and surveying parties sought to drive Indigenous peoples from their lands throughout Texas. The city’s first camping ban excluded Indigenous peoples from camping inside city limits.

Slavery was an integral part of the economy of early Austin, with up to a third of its earliest recorded population comprised of enslaved Black people. White people who enslaved twenty people or more were known as “planters” and held special status. As a consequence of the boom-and-bust cycles of for-profit agriculture, planters often enslaved more people than they could put to work on the plantations that ringed the city. Consequently, many enslaved people worked and lived in the city instead of on plantations. They provided various urban services, remitting a percentage of their income to their enslavers.

Some elements of the ruling classes sought to target these Black people who were enslaved but living somewhat independently. They formed Vigilance Committees of private citizens to maintain white power in the districts where these people lived. Later, they demanded the establishment of a municipal police force so that the public would have to pay for the policing of Black people. This was one of the origins of what became the APD.

A continuing history of white supremacist violence: troopers playing a role in the sweeps targeting the houseless.

Another famously followed the Civil War some years later. With slavery abolished and the fighting over, freedmen and former Confederate soldiers arrived in the city alongside other poor whites. Black freedmen established communities—sometimes permitted on private land, but often squatting near creeks and in other undesirable or far-flung areas of town. To discipline these surplus populations, the city government proposed a police force. The Black Codes forced Black people who did not find employment to labor in conditions resembling slavery. Black work crews assembled that way played a major role in constructing Austin’s State Capitol.

Alongside the police, a series of city plans served to structure the racial order of the city. Following the official decree of segregation in 1928, slums comprising over ten percent of the town’s area were evicted. People who were renting or who did not have clear title to the land where they resided were displaced en masse through these “Slum Clearance Plans” and federally funded Urban Renewal programs, and the land was often turned over to state use (including the sites of the University of Texas, the state government, and the hospitals between Congress and the I-35 Freeway). These displacements served to impose a line between a Black and brown East Austin and a white West Austin. This segregationist project shaped the messy post-emancipation reality of scattered Freedmen’s towns and Mexican enclaves over the following 80 years.

According to Gus Bova, in the 1970s and 1980s, subsidized housing fell out of favor alongside a generalized crisis in manufacturing work. Across the country, people were being thrown out of industrial work while cheap housing was disappearing, and Austin was no exception. The local booms and busts in the housing construction market, which employed low-wage labor, contributed to this. Federal policy also began to support housing as a collateralized asset, both for big banks and consumers, seeing a hot real estate market as a sign of a healthy economy that bolsters consumer spending and debt. Periodically, this policy gets ahead of itself, spawning crises like the one in 2008—but even at the best of times, it inexorably raises housing costs for everyone while concentrating property in the hands of fewer and fewer landlords.

The city’s “Innovation Team” traces the beginning of NGO work intended to benefit the homeless to 1966, citing a charity’s pamphlet offering services to “transients” and “non-residents.” Bova and the “Innovation Team” both point to 1985 as a watershed year in which the city set up the first of many task forces to fight homelessness. Bova concludes that by 1985, the accumulation of crises in employment and housing had produced considerable homelessness in Austin.

Not long after, the Street People’s Advisory Council (SPAC) formed, bringing together rebels from the Task Force with politicized homeless people. Drawing lessons from actions against the Vietnam War, these activists purchased a goose which they publicly threatened to kill and eat, after first considering a swan donated to the city by a member of the local elite. After the goose drew the attention of an outrage-hungry press, they pardoned the goose and named him Homer. Homer and his human compatriots went on to lead occupation marches on abandoned buildings and the flotilla occupation of Town Lake.

Activist Molly Ivins, who camped out in protest of Austin’s 1996 Camping Ban, meets Homer the Homeless Goose.

The SPAC and Homer captured headlines, hearts, and minds for several years, helping to generate an activist milieu that included the Mad Housers (a collective of builders that constructed mobile shelters and the flotilla rafts that were used to occupy the lake) and the Blackland CDC (a neighborhood organization which co-organized the occupation of vacant houses being demolished by the University of Texas in east Austin). They operated as a part of nationwide movements, joining organizations like the National Homeless Union, the Houston Homeless Union, and others in coordinated campaigns, including one dedicated to takeovers of vacant housing.

They won some reforms, including increased shelter funding, the dedication of vacant housing to serve as transitional housing, and a decades-long detente on UT development of the Eastside; but the SPAC campaign was ultimately repressed. The APD consistently hounded the organizers; allegedly, so did other homeless people, and “animal rights” activists concerned for the well-being of the adventurous Homer. City officials played a role in repressing the flotilla protest, changing a “night-fishing” ordinance that allowed the legal occupation of the lake to create new restrictions that made it possible to seize the boats. Nonetheless, the story of Homer and the SPAC and their direct action served as inspiration for activists from the Challenger Street Newspaper to launch several efforts of their own throughout the 2010s.

The next major cycle of struggle emerged in response to Austin’s camping ban in the mid-1990s. Research by Gus Bova locates the impetus for the camping ban in activism by the Downtown Austin Alliance (DAA), a consortium of downtown business and land owners. According to Bova, the DAA was incorporated as a Business Improvement District, a quasi-governmental organization to which businesses pay special taxes to fund private security and political activity. Their first move was to organize “Downtown Rangers” who biked around downtown harassing homeless people and acting as the DAA’s private arm of the Austin Police Department, which supervised them.

Austinites protest the camping ban proposal at City Hall in 1996.

The DAA also began to organize for a camping ban, picking up model legislation from the American Association for Rights and Responsibilities—which shared white nationalist co-founder John Tanton with the anti-immigrant group Federation for American Immigration Reform. Though the ban passed easily in 1996, its passage led to a brief wave of campouts by housed people in protest. A year later, the city council was preparing to repeal it, as it had only served to shuffle people from place to place in the city and deeper into the woods. Amid pressure from the DAA, the council led by then Mayor Kirk Watson “compromised,” keeping the ban but establishing homeless services in downtown Austin. This led to the establishment of the Austin Resource Center for the Homeless (ARCH), which served as an anchor for similar services in the area. It also illustrates the connection between homeless services and policies that police and harm their clientele.

In addition to the camping ban, city police and administrators used their powers to harass homeless people and encampment communities. One example is captured vividly in the 1995 documentary Bouldin Creek Greenbelt Family, filmed by camp residents themselves as well as housed cable access volunteers. The film chronicles the daily life and communal practices of the camp, including a scene in which the residents grill burgers for more than a dozen people for dinner time. This pastoral peace is disrupted by cops on horseback who bark orders at the residents to vacate before sending heavy machinery to destroy their property and territory. The family is scattered about town with whatever possessions they can carry.

The Bouldin Greenbelt Family.

These practices of harassment and disruption met an opponent in the late 1990s in Leslie Cochran, a gender-defying homeless resident who, encountering repression upon moving to town, became a one-man army agitating against the police. Leslie’s crusade—which included city council appearances, elaborately painted signs protesting his treatment by APD, and a run for mayor—put him front and center in the popular imagination of Austin in the late 1990s and early 2000s. His legacy is complicated. His nonlinear, playful relationship with gender made him the butt of jokes about trans people and a celebrated spectacle of the Austin Weird. Many people forget that around his much gawked-at thong, his ass was often painted “Kiss this, APD.”

Alongside Leslie and the camping ban campout, other homeless organizing lacked the thread of direct action and independence that had characterized the SPAC. One such campaign was House the Homeless, established by legal aid worker Richard Troxell. Troxell took credit for creating the concept of the police Winnebago in Philly, and for the one-hour health exemption to the no-sit no-lie ordinance that followed the DAA’s campaign for the camping ban. Troxell, to his credit, acknowledged the roles of both the wage system and the police in creating and perpetuating homelessness, but followed these ideas into increasingly wonkish policy proposals. Also on the scene was the Austin Advocate, which successfully organized the first street newspaper with homeless vendors, including Leslie, staged prominently around Austin. While the Advocate relied heavily on these vendors, the vendors had little role in the writing or publishing process.

A split in the last months of the Advocate led Val Romness, a longtime producer of homeless media involved in the Austin Cable Access scene that released “Bouldin Creek Greenbelt Family,” to establish the Challenger in early 2011 with Advocate vendor Fred Pettit after the Advocate had ceased meaningful production. The Challenger began operations without nonprofit status or funding, operating more horizontally, though helmed consistently by Romness. This openness, along with creative participation by local anarchists, led to increased ties between the paper and radical milieus, with early collaborations with Monkeywrench Books, Austin Anarchist Study Group members, Treasure City Thrift, and remnants of the then-dissipating Rhizome Collective. In late 2011, these relationships helped to foster the Challenger’s intervention in the local iteration of the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement.

When the revolutionary wave that took shape in Tunisia and spread to Tahrir Square in Egypt reached Austin in the form of the Occupy Wall Street movement, the results were mixed. The first General Assemblies were announced by a distinctly Austin mixture of white yogis and libertarians, who hoped for a non-confrontational interpretation of “Occupy.” In contrast to the tent encampments popping up in other cities, they proposed a 24-hour protest at Austin City Hall with sleeping quarters in an electric taxi warehouse several miles away. The ad-hoc leaders cited the camping ban as the main reason they chose this tack, not wanting to break the law and burn bridges with the police, whom they regarded as part of the “99%.”

Challenger Newspaper members saw themselves as a part of this eclectic upswell of the downwardly mobile and called for an alternative encampment called Tent City across the river from City Hall to bring attention to their own issues, including the 1%-driven camping ban. Organizers attempted to rally support from Occupy Austin (OA) participants for a sunset confrontation with police, but APD moved in early, dispersing the camp before it could gather steam. Tent City organizers and anarchists relocated the tents to City Hall and set them up, confronting several more conservative members of OA. Tent City and the Challenger made a bold claim for autonomous action early on with the support of an OWS founder, the late, great David Graeber, who was in town visiting his girlfriend and happened to save a toddler occupant from an overzealous opponent of the tents.

Through shrewd maneuvering and the opposition of a roused crowd, the ones with the tents won a standoff with APD, establishing precedent for a more robust occupation and the participation of the homeless movement. As the occupation wore on, more and more of those in the occupation at City Hall were homeless, sleeping at the site overnight, though usually on the limestone stairs rather than setting up more tents. This led to tensions within the Occupy Austin movement, as some participants grumbled that their movement had been “coopted” by the poor. Against this tendency, and alongside organizing by participants of color, a more radical streak emerged, making space for a diverse array of voices and actions. The “anniversary” event in 2012 was led by Challenger/Tent City-oriented occupiers. The Challenger had moved its weekly meetings to the occupation and was organizing within it through the Ending Homelessness Working Group (EHWG). On the first birthday of Occupy Austin, the EHWG, the OA General Assembly, and the Challenger called for a march on the City-owned vacant Home Depot building with the intention of occupying it, taking inspiration from OWS and Occupy Oakland.

The march on the Home Depot was unsuccessful, but led to several other attempts to occupy other vacant lots around Austin. Homeless occupiers established a camp, also called Tent City, in South Austin, which focused mostly on recreating daily camp life rather than advancing political conflict. Though it was intended as an experiment, the camp hosted a small group of members mostly focused on avoiding the cops, not unlike other camps. It gradually disbanded after several evictions, without the sort of flashpoint of camp defense that might have re-politicized it. Its fizzling led to questions about what sort of organizational capacity successful camp defense would require, questions later consciously taken up by Stop the Sweeps Austin.

Tents line the trail along the Colorado River on the south edge of downtown Austin.

Surrounding the City from Below

From 2019-2022, the camps that surrounded and besieged the Capitol practiced an ungoverned and unregulated form of life that violated the order of capital. Recognizing the camps as forms of insurgent self-organization on the part of the dispossessed, we sought to defend them and expand their potential in the face of attacks from a wide array of political forces. This runs counter to the logic of specialization and legibility that typically characterizes activist campaigns, which often aim to represent the dispossessed as a distinct constituency (“the homeless”) through demands and negotiation on the terrain of policy, recruiting to an organization to negotiate on their behalf, and cultivating a specialized minority of “directly-impacted” activists. Instead, we emphasized the defense, generalization, and expansion of forms of insurgent self-organization that are illegible to politicians, social service providers, and activists alike. Where much of the NGO left saw a lack of organization, demands, interests, and representatives, we saw an abundance of potential in the camps themselves.

We did not romanticize camps as the revolutionary communes-to-come. Different camps had different cultures and different levels of cohesion. In some camps, people took lots of responsibility for each other, checking in to ensure others were fed, warm, and healthy, with those taking responsibility for assisting others and mediating conflicts forming an organic leadership. In other cases, big personalities declared themselves leaders, with mixed reactions from other residents ranging from dismissiveness to outright hostility. Some camps’ internal dynamics were defined by competition and hostility, with fights and thefts common as people merely tolerated living alongside each other. People would often move between camps as a consequence of conflicts with other residents or as a means to seek different conditions in regards to drug use, fights, noise, pests, or other issues. Recognizing the camps as self-organized phenomena means taking all these contradictory realities into account while still affirming the self-activity at their core as a response to a shared condition of dispossession.

Whatever the internal dynamics of each camp, their occupation of public space constituted an attack on the logic of property and capitalist development. Land belonging to the city or state government was taken over by forms of organization beyond their control and put to unauthorized and unregulated uses. While privately held property was never directly taken over, the public presence of the dispossessed rendered class conflict explicit and impeded development. The proliferation of camps in close proximity to sites of commerce or luxury apartments made these places less appealing to the comparatively wealthy, who complained about the numerous signs of the dispossessed living their lives in public—including accumulated survival supplies, the buildup of waste from humans living without infrastructure, and public expressions of mental and emotional crisis and other things that those with houses have the luxury of doing in private. A public homeless population coming into contact with students, tourists, consumers, and investors threatened to make Austin an unattractive location for new festivals, conferences, companies, and residents.

The proliferation of camps from 2019 to 2022 was an impediment to development and gentrification in Austin, alongside and overlapping with system-wide shocks including the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic downturn, and the George Floyd Rebellion. While the camps are sources of power that impact the political and economic terrain around them, they are not properly political: they do not make demands, they are not legible forms of organization or constituents that can be represented. In recent years, others have used the term ante-political to refer to forces that precede or exceed the traditional sphere of politics. This framework helps us understand the power of the camps and the nature of the political attack on them.

The attack on the camps and on the unhoused in general was carried out according to two distinct logics of governance. One is outright exterminationist, its aim being to socially cleanse undesirable populations by dispersing the camps and driving people out of town or into jail cells. The other is managerial, the aim being to regulate the homeless and precarious through services and facilities administered by the state, social service providers, or private and non-profit landlords. The former attacks the camps for simply existing; the latter aims to subjugate their ungoverned activity to managed and profitable social services. Both attack them for violating capitalist order. The same institutions can make use of both logics, like when Governor Greg Abbott opened a Texas Department of Transportation parking lot—now known as Camp Esperanza—as a “shelter” to regulate the homeless and legitimize his sweeps, or when the city government used sweeps to enforce the newly reinstated camping ban in 2022.

A hole in the fence at the sanctioned camp opened by Governor Greg Abbot on a Texas Department of Transportation lot in 2019.

The mainstream movement to repeal the camping ban framed the struggle as a conflict between conservatives and progressives: Greg Abbott and the reactionaries of Take Back Austin on one side, Austin’s social movements, city council, and social service providers on the other. This battle was encapsulated in the ongoing Twitter war between Abbott and Adler over the camping ban repeal. In reality, both the state and city governments depended on the sweeps to manage homelessness, only according to distinct logics. Before the repeal of the camping ban, the city government had been sporadically using sweeps to clear camps, and they kept their own sweep schedule parallel to the state government’s sweeps under the highways. When sweeps resumed after pausing for the pandemic, the city government had taken over all of the sweeps from the State. This shared dependence was most explicitly laid bare when the city government swept the ARCH camp the same day the state government began its sweeps of the highways.

Re-framing the camps as an ante-political insurgent force can give us a clearer picture of the competing forces that aim to attack this form of insurgency, enabling us to move away from some of the limitations of activist frameworks. Reformist activist approaches can lead us into the trap of allying with the managerial logic of governance in the name of pragmatism, as seen in groups like The Other Ones Foundation (TOOF), Austin Mutual Aid (AMA), and Little Petal Alliance (LPA). More radical activist approaches can end up fetishizing the thinking and activity of the activists themselves, creating organizations that exist for no sake but to reproduce themselves or insular scenes that become disconnected from any material force. Rejecting both of these errors, we believe that focusing on our relationship to existing forms of insurgent self-organization can provide a counterweight to both reformist managerialism and radical impotence.

While Stop the Sweeps used activist tactics, we did so while understanding the insurgency of the camps as primary, rather than our own activity. Faced with the practical question of how to join forces with the camps and mount a defense against sweeps, we recruited and mobilized from within activist milieus, and we used activist tactics such as creating media, pushing limited demands (but not policy), rallies, home and office demos, and call-ins as part of campaigns against specific targets. Similarly, after Abbott opened what eventually became Camp Esperanza, we maintained an early presence to build relationships, trace the fault lines, and conspire with the residents to undermine this new form of management. When the COVID-19 pandemic created a crisis, we participated in shaping the camp support infrastructure that filled this gap, temporarily helping sustain the camps while developing new forms of collaboration with them. But we did so with a determination to bolster the defense of the camps, not seeing these things as ends in themselves, nor claiming to “organize” the homeless or integrate the camps or their residents into the terrain of political representation.

Now, on the other side of this movement arc, we feel it is important to re-articulate this position, which may have been forgotten amid the frenzy of service-oriented mutual aid, activist infighting, and reacting to our enemies’ offensives.

Governor Greg Abbott, scumbag.

Asymmetrical Conflict against the Infrastructure of Oppression

Informed by the tactical sensibility emerging through the last two decades of struggle—the port shutdowns during Occupy, the highway takeovers during Black Lives Matter protests, the targeting of ICE and prison contractors, and other struggles that we have participated in or learned from—Stop the Sweeps understood power as a question of infrastructure and logistics. Decision-making bodies are largely empty political theaters carrying out the will of dominant social forces—be those reactionary populist movements or factions of capitalists, non-profits, or police. Their emptiness makes demonstrations at the well-guarded halls of power ineffectual. The real power in this world is in the infrastructure that is used to administer and maintain this civilization; a decision to carry out sweeps can only be enforced if there are workers, trucks, and money that can be mobilized to that purpose. Infrastructures can be vulnerable to pressure, and this makes it a strategic site for potential pressure and direct action.

We understood that City Hall and Abbott would never willingly stop the sweeps. Instead, once the state government started conducting sweeps in November 2019, we paid attention to who was conducting them. The sweeps were carried out by a work crew driving a few contractor trucks and overseen by a couple supervisors directly from the Texas Department of Transportation. The police were not actively removing people’s belongings; they served as a passive backup force that intervened only to suppress unrest or resistance. They were largely hands-off with us, allowing us to be in the camps as we filmed, harassed the work crew, and talked to residents. We noticed the same dynamic when the Austin Public Works Department carried out sweeps in November 2019 along other public easements with a different contractor’s name on the truck.

A group of contract workers throw away belongings at a sweep under a highway overpass.

Digging through city and state contracts, we traced a whole web of contractors. We discovered that the city and state both contracted through WorkQuest, a central contracting agency offering services and products and employing disabled people. WorkQuest, in turn, contracted out to other agencies: EPSI for the state sweeps and Relief Enterprises for the city sweeps. Sometimes these subcontractors also recruited labor from temporary staffing agencies like Pacesetters or received people doing “community service” through Downtown Austin Community Court. Sometimes the work crews themselves consisted of other homeless people, though some we met ended up leaving because they couldn’t stand to participate in oppressing other people in the same position as them.

Once we uncovered the contractors, we saw the WorkQuest contract as a strategic vulnerability. Our theory was that if there was enough pressure to make contractors back out or make the sweeps more costly, it would diminish the political will to carry them out. We hoped that if WorkQuest dropped out, it would impair both the City and State from doing sweeps. We identified the phone numbers of WorkQuest employees, the locations of offices, and the addresses of executives; we used these for targeted phone zaps, a home demo, and a guerrilla fliering action at the WorkQuest store. This strategy draws a lot from the “tertiary targeting” model used in the Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty campaign and more recently in the Stop Cop City movement. While the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted our focus on WorkQuest, we learned months afterwards that they had dropped the contract in March 2020 due to our pressure.

A home demo.

Unfortunately, WorkQuest dropping the contract did not stop the sweeps. As the city government took over the sweeps in the fall of 2020, WorkQuest passed off the contract directly to Relief Enterprises; we had only removed the middleman. Relief Enterprises had fewer physical sites to target; we had little luck finding a truck lot where we could mobilize a blockade or some other collective action. The few locations we did find appeared to be shared with other businesses in industrial parks, and the vehicles appeared to be dispersed between a few sites rather than concentrated in a single lot. Much of our energy targeting them was directed into call-in campaigns to City Hall when their contract came up for renewal, or car demos targeting the Mayor and City Council members. Beyond the car demos, we lacked effective ways to mobilize groups of people offensively during the height of the pandemic, and our energy was tied up in other initiatives like the camp support network.

From 2020 to 2022, we succeeded in using these methods to win concessions that softened the sweeps. The authorities let people keep their tents and belongings, permitting them to name what was and was not trash and to remain in their camps during the sweeps; the City tried to frame them as progressive “clean-ups” to appease critics. While they continued throw away furniture, mattresses, structures, and temporarily unattended belongings—and we continued to push back on each of those fronts—these sweeps were a far cry from the early Texas Department of Transportation sweeps that forced people to move all their belongings across the highway or lose everything.

All these advances were undone when Prop B, a reactionary referendum initiative spearheaded by local anti-homeless forces with Save Austin Now, reinstated the camping ban and the sweeps returned as a force of devastating displacement. Since we had tied up so much of our energy in pressuring City Council alongside initiatives like the camp support network, we had not built up the forces we needed to take the fight directly to the sweeps infrastructure once the political terrain was closed off to us. By the time Prop B came down, the movement was already declining, and it was too late to reorient towards a new strategic framework. When we got started, we had been critical of Homes Not Handcuffs for only pushing the policy front without building the capacity to defend that victory against the inevitable reactionary backlash. In our pursuit of political leverage on the sweeps contract, we fell into a similar trap: we had not built up the power to defend the gains we had made against an inevitable reaction in the political terrain.

In our experience, an infrastructural understanding of power also opened offensive paths for us to avoid getting locked into head-on, symmetrical conflicts with better-resourced adversaries. It does not usually make sense to attempt to meet our enemy’s repressive forces head on with greater numbers or force—whether in a defensive attempt to hold a space against a siege or an offensive attempt to besiege the guarded fortresses of our enemies (City Hall, the Capitol, downtown). While there are conditions under which such confrontations are strategic, in general, we have found that if a movement’s strategy is defined around pursuing those, this will exhaust the movement, incur defeats, and reduce it to largely reactive activity. An asymmetrical approach instead considers where our adversaries are weak, how to stretch them thin by going where they are unprepared, and finding pressure points that maximize impact—such as the infrastructure undergirding a project. This enables a movement to take the initiative, forces its adversaries to respond from a position of weakness, and creates the conditions to win victories and mobilize greater forces.

We learned some of these lessons the hard way in camp defense. While the initial defense of the ARCH was inspiring for stopping a sweep head on, it also illustrated the difficult of repeating such a victory: our adversaries could come back at any time, and being ready to stop them on short notice would have required an unsustainable level of vigilance and capacity for rapid response. Similarly, the weekly schedule of the highway sweeps meant that one day’s victory could be swept away by the work crew’s return the next week. By pivoting to an asymmetrical conflict model, targeting WorkQuest with pressure at places we weren’t expected, we opened up new fronts and took the initiative, acting on our own schedule rather than responding to the sweeps schedule.

The camp outside of the Austin Resource Center for the Homeless (right) and its late-night removal by city workers armed with a mechanical claw (left).

This does not mean that movements should abandon defensive fights, but that we should shift our approach to them. Asymmetrical approaches de-emphasize holding terrain at all costs, while recognizing it as essential. Rather than an all-or-nothing fight, defending terrain becomes a question of maximizing the costs for our opponents, minimizing our own losses, increasing combativeness and offensive opportunities, and rebuilding or seizing new terrain after the siege. Even when our movement was smaller, our efforts were strongest when they balanced tactical, defensive retreats with counteroffensives against the infrastructure of the sweeps.

We continued to maintain a presence at sweeps, where we aimed to maximize delays, build connections and courage to support resistance in the camps, and help people rebuild afterwards. We knew that the sweeps operated according to a tight schedule, and that substantial delays along their route would either force them to come back another day, delay a sweep until the following week, or impact their obligations to other contracts. We reasoned that any delays we could force might give some relief to those further down the schedule who would get passed over that week, and that delays would drain more money and labor out of the contract. We also helped people to replace the tents and other survival gear that they had lost in sweeps in order to minimize the impact on people’s lives and ensure that the camps could persist.

Employing this strategy, we achieved a couple major victories when entire camps resisted the sweeps, refusing to move or harassing the sweeps crews to slow them down. Some of these moments of resistance emerged spontaneously; others only after sustained efforts building direct relationships that gave us a basis of trust and courage to act alongside camp residents. Based on internal emails from Public Works, we know that our presence was a major nuisance for them. Eventually, they cracked down on our ability to mess with the sweeps from within the camps by enforcing a “work zone” rule allowing them to arrest people for trespassing while a sweep was ongoing.

An early graphic used by Stop the Sweeps to orient new volunteers to the wide range of ways to engage a sweep.

By the end of the sweeps defense movement cycle, many of these lessons had been forgotten or had not spread widely enough, or we simply lacked the capacity to act on them. We had lost the ability to put pressure on the infrastructure of the sweeps or to turn the conflict into an asymmetrical one rather than a head-on clash. By 2022, due to the enforcement of the work zone rules, sweeps watch crews were unable to do much more than bear witness to the suffering of others or help them move their belongings. At a moment when the movement was declining, some tried to mobilize larger groups to resist each sweep head on, but these groups never really materialized. Actions like the City Hall occupation, while politically important in other ways, remained focused on targeting the symbolic halls of power rather than the material infrastructure of the sweeps. There was one small appearance at the home of the Relief Enterprises CEO, but it was far less forceful than the 2020 home demo against WorkQuest.

While it likely would not have stopped the post-Prop B sweeps, it remains an open question how returning to an understanding of the infrastructural nature of power and a strategy of asymmetrical conflict might have opened new avenues for the movement when it was facing decline. What if sweeps watch didn’t just invite people to bear witness to devastation, but converted camp defense into highway blockades that stopped the circulatory system of the city? Such a strategy could have employed the car demo tactic as well. What if the occupation of City Hall had targeted the offices and homes of sweeps contractors, or other politically and economically important parts of the city beyond the trap of downtown?

There are no guarantees, only possibilities and questions to bear in mind in future fights. But it is essential to recognize that for now, our enemies are much bigger and better equipped than us, and we are strongest when we target their weak points rather than being drawn into direct clashes.

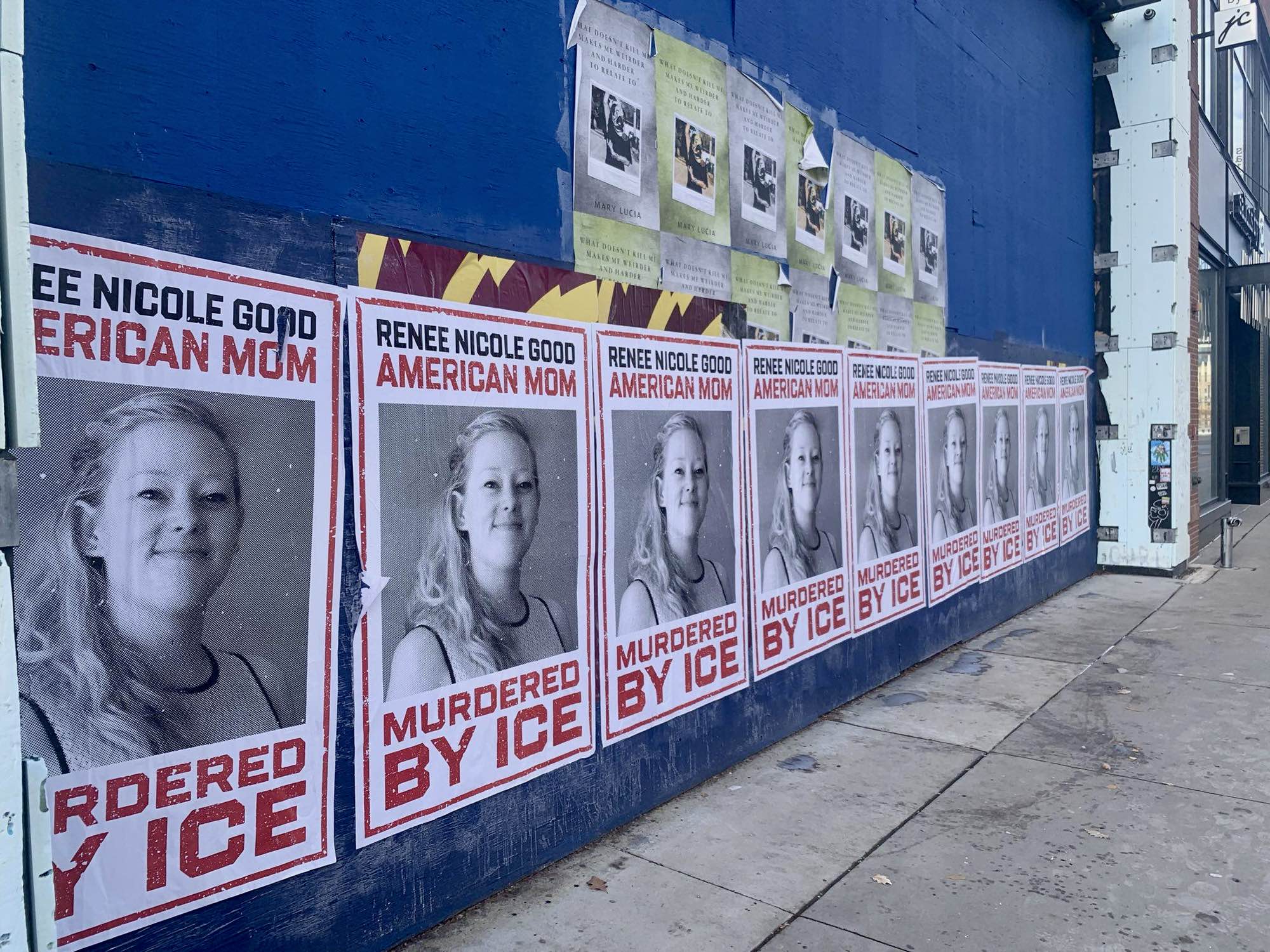

Posters left behind after a small 2021 home demo at the home of the CEO of Relief Enterprises, the contractor responsible for the sweeps since 2020.

Movement Polarities

One of our hypotheses, tested and refined through our experience in Stop the Sweeps, is that what we call social movements can be better understood as an open field of forces, each engaged with others to various degrees in relationships of collaboration and contestation, affinity and hostility, coalition and competition. What we describe as a “movement” is an emergent culmination of the interplay of these forces, irreducible to any sum of its component parts. Distinct actors within this field might be understood as poles—rallying points around which cohere a set of ideas, strategies, and ways of acting. These poles exert forces within the field of the movement, attracting new people and connections, pushing back on others, and spreading or clashing with other ideas within the terrain. Some poles may be able to affect those around them through their actions, transmitting ideas or causing shifts in the field of possibilities; other poles may find themselves isolated or ineffective, unable to act on their own terms or influence others.

This view of movements as a field of forces and polarities clarifies a few things. First, it directs our focus not just to what an individual or a group is but to what it can do—how it affects the field of the movement and others in it. This emphasis on doing can help us let go of anxieties around recruiting people to join our organizations, focusing us instead on ways to spread autonomous and militant ways of acting. Influential poles can generate powerful proposals, models, or invitations to act that spread across crews, organizations, and networks. Furthermore, we can better understand the lines of transmission between groups, factions, and ideologies in movements through this framework. Rather than perceiving distinct sects (as implied by the term sectarian), we can discern how the force exerted by a pole can overflow the boundaries of a particular organization, or how people and groups themselves can move between different poles of a movement through their activity.

Using this framework, we can perceive and act upon the possibilities latent in open-ended situations. We can see how these situations emerge as organic reactions to flashpoints of oppressive force; we can grasp how a protest movement can reach a scale and intensity that escape the control of those who “organized” it to become more potent and infectious. Perceptive and strategic militants can find the openings in such moments to contribute in ways that help to shape the outcome—forging new relationships, advancing new strategies or tactics, and enabling greater coordination, self-organization, or escalation. In Stop the Sweeps, this was one of our greatest strengths, whether we were engaging with a sweep, the waves of activity in the course of the George Floyd Uprising, the Abbott encampments and city COVID hotels, or rallies and occupations initiated by other groups.

Stop the Sweeps emerged to fill a gap in the existing movement. While the Homes Not Handcuffs (HnH) coalition had secured the legislative victory of repealing the camping ban, they had failed to build the political force necessary to defend their win. So, when the city government responded to a wave of reaction a few months later by sweeping the ARCH at the same time that the state government cracked down with sweeps under the highway, the non-profit coalition was caught flat-footed. They scheduled a meeting at Street Forum the weekend before the sweeps to plan a response that would focus on legal observing, documentation, media campaigns, and continued legislative advocacy. The non-profit coalition kept most of its focus on Abbott’s exterminationist rhetoric, drawing no attention to the city’s or NGO’s use of sweeps to control the unhoused.

The cell that became Stop the Sweeps began as a group of friends who started showing up in the mornings at the camp outside the ARCH in anticipation of the sweep. The timing of these sweeps was left vague and constantly delayed; but keeping this rhythm for two weeks led to a series of connections with people at that camp and some strategic conversations among the handful of us. When the announcement finally came that the ARCH sweep would occur on the same day as Abbott’s sweep of the camps under the highway, we had already laid the groundwork for launching Stop the Sweeps.

A Homes Not Handcuffs rally at the Texas Governor’s Mansion in 2019, protesting Abbott’s threats to sweep camps.

When we attended the Homes Not Handcuffs response meeting and noticed that their plan did not include any attention on the sweeps at the ARCH, nor plans for direct resistance to the sweeps, we decided to break out into our own group adjacent to their meeting. At that meeting, we developed our own plan to mobilize a combative presence at the ARCH. While we could not stretch ourselves to mobilize on multiple fronts, we retained some presence at the highway sweeps to support any organic resistance to them. We took the name Stop the Sweeps—both a demand and a form of action—and put out our own call to action on our nascent socials.

Rather than attempting to convince the HnH coalition to adopt a more confrontational strategy (or calling them out for their failure to do so), we identified an opening in the movement where we could act and filled it. We sidestepped direct conflict with the non-profit wing of the movement in favor of opening up space for autonomous action alongside the non-profit’s strategy. Seizing the opportunity to mobilize where the rest of the movement did not have a presence was advantageous in this regard, and helped avoid conflicts over “hijacking” or about escalating beyond the risk tolerance of HnH. Similarly, while those of us at the highway camps communicated with HnH forces on the ground, we made separate decisions to support unhoused people planning to resist the sweeps while the others focused on their strategy.

Making our own plan enabled us to connect with other scattered forces, both within and outside the movement, that had been looking for more combative forms of engagement. In the days leading up to the ARCH sweep, we connected with members of the DSA-LSC who were involved in HnH and hungry to employ direct action tactics against the sweeps. They were able to leverage some of the contact lists that the coalition had not utilized, using email blasts and phone banking to turn people out to the ARCH. Through our existing connections, we were also able to pull in friends from anti-fascist and anti-police organizing.

Consequently, a small group without its own base was able to bring together about thirty people on a Monday. We temporarily prevented the destruction of the camp at the ARCH—at least, until they came back at 4 am.

From its inception, Stop the Sweeps existed in this delicate balance between maintaining connections to other actors in the movement and acting on our own terms. We attended the meetings that Homes Not Handcuffs hosted and maintained lines of communication with people in those groups; at the same time, we planned our own ways to engage on the ground, created our own narrative, and called our own actions. Calling our own action at the sweep that Homes Not Handcuffs had decided not to respond to was one example of this; mobilizing to support unhoused people who planned to resist the sweeps under the highways was another.

Homes Not Handcuffs held one more meeting after the sweeps started. We attended and made up most of the “sweeps defense” breakout group; the other two groups were focused on policy advocacy around criminalization and housing. We ultimately absorbed the sweeps defense group into our efforts; we later learned that the other groups never got off the ground after that meeting. The consolidation of this pole and its rapid growth gave us the momentum to transition into confronting the Texas Department of Transportation’s weekly sweep schedule after November 4. As the only group still actively following, resisting, and shaping the narrative around the sweeps, we were able to shift the movement towards a more radical position.

Mercenaries destroying the homes of the houseless.

A few months into our work together, we had started to develop relationships with a wider range of groups. Seeking to increase the coordination and strategic intelligence of the movement, we initiated a closed assembly called The Hive. We framed it as an assembly that we were curating to be focused on shared action and reflection, explicitly not a decision-making space. The space was organized around three central principles: priority to grassroots, autonomous groups over non-profit and political organizations; a commitment to not undermining the work of other groups; and a commitment to not collaborating with the police against other wings of the movement. This last principle was intentionally crafted to make space for groups organized at state-run camps, which navigated complex relationships with the police and security that governed them, while holding a line to insulate the rest of the movement.

The Hive brought together a wide range of factions including non-profits, self-organized homeless collectives, the street newspaper, DSA, mutual aid groups, tenant organizers, and harm reduction groups. It served as a venue for communication and cross-pollination across different groups and fronts of the struggle. At various points, the assembly grappled with questions related to squatting and takeover schemes, pushing back against policing in the COVID hotels, and forming locally-rooted support and defense groups for camps. Many of the relationships that formed through this assembly came to form the initial core of the Camp Support network.

Building on the relationships formed in the Hive, we were positioned to bring groups together to build out the Camp Support mutual aid network after existing social services shut down following the outbreak of COVID-19. One comrade connected us with a church kitchen; the local Food Not Bombs chapter provided know-how and a network of cooks to start sending out meals. As we met more groups after the George Floyd Uprising, we were able to help them connect to this work in addition to sweeps watch, bringing together a dozen or so small organizations offering everything from harm reduction to resources for sex workers. At first, the success of this network underlined the painfully slow response of the city government to the public health crisis.

This was complicated when city resources finally caught up months into the pandemic and approached the network about using our volunteers to shuttle its prepared meals. The network accepted this deal, opting to use them as we pleased and to build what we hoped would be fighting relationships with camp residents. This part of the mutual aid work remained underdeveloped; the volunteers who brought food only showed up to fight alongside people at sweeps on rare occasions. Camp support coordinators did use their access to city food program meetings to pester city bureaucrats into putting pressure on the agencies running sweeps, and this was one prong of a successful effort to defeat most of the sweeps during the initial months of the pandemic.

Our ability to act decisively and maintain a wide range of complex relationships with other formations depended in large part on the high degree of trust and shared context within the core group of Stop the Sweeps, which emerged from our long-term relationships and experience throwing down together. The strong connections among our core group enabled us to take bold action and gave us the emotional resilience to engage in more complicated coalitional relationships with tact and grace. We had space to voice and think through critiques of other formations and strategies and to reflect on our relationships to other groups despite our differences. This helped release pressure and avoid unnecessary direct conflict.

As time went on and some of our initial crew stepped back, we started to bring in new people we met through our activity. We developed a set of principles and a process for onboarding people, emphasizing experience working together and a sensibility that resonated with our principles and strategy. We avoided rushing to recruit people, and emphasized the many ways to get involved in specific forms of activity that did not require formally joining Stop the Sweeps—such as planning specific actions, coming to the Hive, and coordinating around sweeps defense. This process helped to expand our crew and bring in new energy at crucial moments, especially when the movement was beginning to scale up and we encountered a number of other fellow travelers.

This also meant that the group composition slowly shifted so that there were fewer long-term, high-context relationships in the group. Eventually, many of us only knew each other from the movement against sweeps. As the latter phases of the movement brought more intense conflicts and we encountered new limits, members of our crew responded differently to these situations. Some members pushed to engage more directly in the intra-movement conflicts, such as by making demands of Austin Mutual Aid (AMA).

Unhoused people and activists rally at an encampment set up at City Hall by Little Petal Alliance in response to the passage of the new camping ban.

When Little Petal Alliance (LPA) launched an occupation at City Hall in response to Prop B, our group was divided in new ways. Some members saw the occupation as an open-ended situation full of potential and self-organization that exceeded any one group, and wanted to engage with it; others were wary due to a combination of tactical critiques and legitimate criticisms of the harmful and opportunistic behaviors of members of LPA. When the camping ban ushered in the demolition of camps, some members pushed for more urgent activity and took out their frustrations on other participants in the movement. Most devastatingly, this led to a split with one of the unhoused activists who was a founding member. Our experience demonstrates the need to remain attuned to how the changing composition of a group over time, alongside shifting movement conditions, can change the forms of trust and collaboration that are possible, even if it nominally remains organized around the same principles and strategy.

Understanding our activity in terms of the constitution of poles allows us to evaluate our relationships with other formations on the basis of what they make possible or foreclose. Relationships with other groups—even those with whom we have significant differences when it comes to our orientation towards demands, reform, the state, or other institutions—can open up opportunities to leverage information, increase our ability to circulate proposals and influence other factions of the movement, and produce openings for creative forms of activity. If we understand the porous, shifting, open-ended nature of all groups, we can see how they might transform in the course of a movement. Cultivating relationships with groups that work with the state while maintaining our own irreducible antagonism towards it can create new tensions, reshaping the demands of other wings of the movement and making it more difficult for the authorities to divide a movement into those they can co-opt and those they can repress.

The central consideration in such relationships is to keep the initiative and always maintain autonomy. Relationships can also have the effect of stifling possibilities rather than generating them; we can stifle our own initiatives for fear of upsetting other factions, end up tailing other formations, or become absorbed in the efforts of other groups. Maintaining the initiative within the field of movement polarity moves us away from the habit of merely critiquing other groups’ activities that we disagree with, so that we focus instead on how to develop and spread our own ideas and models for action as we collaborate and compete with others for influence.

These relationships require minimum standards of respect. Active hostility or denouncements, undermining others’ efforts, collaborating with the state against other wings of the movement, or acting as an extension of state, politician, or capitalist influence over the movement often precludes such relationships. Such dynamics have often defined the relationship between autonomous groups and other factions of movements, whether reformist, non-profit, or authoritarian left. However, it is not inevitable that these relationships must always be antagonistic. An understanding of movement polarity can identify the avenues for collaboration beyond simplistic ideological categories, so that autonomous groups can avoid becoming trapped in a self-fulfilling prophecy of conflict with everyone else.

Our relationships with Homes Not Handcuffs enabled us to receive and leverage certain forms of information regarding the motivations of city council members and the dynamics between them, upcoming meeting items and policy changes, and pressure points and information about the effects of our actions on the departments enacting the sweeps. We were also able to produce scandals as a means of shaping the demands that HnH brought to City Council, which enabled us to exert influence on the negotiations without participating in them. At the same time, we were able to continue agitating against the city departments and social service providers that the coalition negotiated with.

This framework also helped us to locate our work in this particular campaign in relation to the broader radical milieu in Austin. In 2019, the organizing terrain was complicated for autonomous organizers. Most organizing was dominated by non-profit organizations, the vast majority of which were hostile to more radical activity. There was a range of progressive non-profit and community advocacy organizations that had more radical political ideas, but whose activity was mostly oriented around policy advocacy and rallies at City Hall. Within the radical milieu, the Maoist milieu surrounding Red Guards Austin (RGA) had absorbed many of the people looking for more militant activity who were dissatisfied with the community organizer scene. As a consequence of sectarian conflict with other movement organizations, abusive authoritarian dynamics, and reckless disregard for their members’ well-being, Red Guards Austin had poisoned the well for militant activity. It was hard to engage in militant organizing, criticize non-profits, or even to wear a mask without being accused of being part of Red Guards.

An encampment at City Hall.

Part of our goal was to use our activity in Stop the Sweeps to open the field for more activity beyond the influence of the non-profit organizations and the Maoists. We developed a way of acting that emphasized autonomous principles without explicitly flagging ourselves as anarchists. We experimented with ways to push the tactical repertoire of the movement without entering into direct conflict with other factions or alienating potential collaborators. Many of us were intimately familiar with the caustic effect that the Maoists specifically had on movements that they entered and knew that we could not maintain our autonomy or initiative while working with them. We also knew that they thrived on direct conflict and polemics against other groups. So when they made attempts to gain inroads into the movement, we simply ignored them and did our own thing.

There is a long history of conflict between the autonomous factions of various movements and those oriented towards reformist negotiations or party organization building. In some cases, the strategies of autonomous militants contribute to this dynamic, particularly when they create a situation in which the contradictions between groups are resolved through a simple sorting of ideological or tactical alignments. Call-outs and polemics, direct conflict with reformist or “less militant” factions of a movement, and filtering all political allegiances through a rigid ideological filter can mirror liberal denunciations, collaboration with the state, and peace policing.

Ideally, the framework of movement polarity offers an experimental path beyond this impasse, though it can challenge assumptions about the role of ideology. How correct our critiques are will make no difference if they only result in us constructing isolated cliques instead of developing the ability to intervene in complex situations. Our hypothesis is that positioning ourselves within these contradictions rather than forcing them towards a simple resolution can open up generative possibilities. We hope others will test and refine this.

Using and Being Used: On Media and Communications Tools

We were media savvy yet media critical. This is rare in a milieu divided between anarchists who oppose any engagement with media on principle and anarchists whose primary form of communication is the Instagram-Infographic-Industrial-Complex.

We used social media as a tool to develop our own narrative and analysis of the sweeps. Every week, we would get practice writing reports on the previous week’s sweeps—drawing attention to their cruelty and to the growth of the resistance. This regular rhythm helped us document the sweeps at a point when most of the media coverage had dried up along with the attention of the larger organizations. As our posts spread—sometimes, ironically, due to reactionary hate comments boosting our performance in the algorithm—we were able to invite more people to join us in sweeps watch. For those who wouldn’t or couldn’t join, combining these posts with calls for phone and email blasts offered ways to enable spectators to participate.

At the same time, we strategically engaged traditional news outlets. We had access to some media contacts thanks to Homes Not Handcuffs, and we mobilized a number of these outlets to cover the ARCH sweep and create political pressure around it. In the process, we developed a number of relatively friendly media connections who helped to circulate our narrative and occasionally follow up on reports and questions that helped to inform our campaigns.

Austin police move to arrest a homeless Stop the Sweeps member who set up a protest tent outside of the downtown homeless shelter after the camp there was evicted.

At a certain point, we were able to use an offensive media strategy to produce scandal. Whenever we caught the sweeps crew on camera in an egregious act—throwing out water during the height of summer, destroying camping supplies in violation of their stated “clean-up” policies, or harassing and threatening sweeps watch volunteers—we could circulate the media and draw negative attention. Sometimes, this alone was enough to exert pressure on the higher-ups, and we saw the crews act differently on subsequent sweeps.

Sometimes, we took this further. We would generate a scandal, then tap one of our friendly media contacts to reach out to the relevant city department or company for comment. The department, trying to maintain public legitimacy, would make some minor concession to something we were demanding. The journalist would tweet out this response and, without waiting for a formal article, we would seize on this as new “policy.” Then we would launch a new set of demands, always pushing the envelope. We did not treat these demands as points of negotiation, but as discursive trenches—as soon as our enemies made a concession, we would dig new a new trench to keep pushing them further, ensuring they remained on the back foot. Combined with phone zaps and on-the-ground resistance, this approach de-fanged the sweeps for most of 2020.

Whether we were publishing our own reports or engaging with journalists, our strength came from developing our own strategy for engaging each of these media forms rather than letting them impose their logic on us. We used social media to circulate report-backs, but we avoided using it for discourse or petty conflict; we did not subordinate our political activities to the pursuit of followers or engagement. Similarly, we used corporate media to circulate our analysis and to produce scandals for our opponents while refusing to get mired in concerns about optics or respectability. Releasing a press release for a home demo was a way of seeking publicity on our own terms. We intentionally avoided news stations that we knew were hostile; we did not fetishize talking to media as an end in itself.

All media and communication tools contain their own internal logic. If we don’t intentionally impose our own logic on them, they will impose their logic on us. Our movements already recognize how corporate media represent specific class interests. We are starting to become aware of how social media do the same—from outright censorship to the ways that algorithms privilege certain forms of interaction while suppressing others, thereby shaping how we think, act, and relate.

This became especially clear to us as we reflected on one of our most-used tools, the Signal chat.

What happens when all organizing moves to Signal?

Early on in our campaign, we used Signal chats in limited ways. We communicated via one core chat for the Stop the Sweeps crew. Some of us maintained a small text blast system that we would plug new contacts into; we used this system to announce upcoming sweeps and bring people out to sweeps watch. We would follow up with them in direct messages, then orient them on the ground. This worked well enough until one week, the person bottom-lining follow-up fell ill. To streamline communication, they made a Signal chat including all the people who would be coming out for sweeps watch that day so we could coordinate with each other. Over the next few weeks, this pattern of starting coordination-focused group chats for sweeps days continued until we created a general sweeps watch chat, where a growing layer of participants from outside the core group could share information and self-organize breakout chats for specific sweeps.

The sweeps watch Signal chat became the movement’s defining platform. As we encountered new allies and plugged them into sweeps defense, they would be added to this chat. The chat took on a life of its own, with people announcing upcoming sweeps and self-organizing separate chats for each week’s sweeps. At first, most people in the chat probably knew most other people in it, or else came to know them by participating in sweeps watch. The conversations were mostly limited to sweeps-related planning. The big Signal chat enabled us to scale up our organizing by taking the labor of follow-up and orientation off our hands: someone new could connect with other people on the ground and get the lay of the land from whatever experienced people were there. Creating another large channel to coordinate camp support—complete with its own array of breakout chats related to specific projects, infrastructure, and camps—increased the movement’s capacity to scale.

If you’ve been running in activist circles long enough, you know where this is headed.

At some point, the Signal chats hit a crucial turning point. They had expanded in size, in part due to the ballooning camp support network that was bringing new people into sweeps watch. By that time, a large number of the participants had not met each other. The expansion of the movement ecosystem meant people in each chat were likely involved in a number of other projects, with varying degrees of affinity or tension with other groups in the ecosystem. While this communication system worked for a while, it began to break down around the same time that the movement began to hit other limits.