Border controls give the authorities an opportunity to invade our privacy and gather information. We would all be a lot safer if we could agree to a standard security protocol for how to approach crossing borders, as carelessness with our own security can impact others as well. The following guide details how to minimize the various security risks involved in legally entering the United States—whether by land, air, or ocean. It draws on the experiences of many anarchists and subversives, both US citizens and not, including some targeted by the security apparatus.

Among anarchists, it has become expected practice not to inform on anyone to the authorities, to refuse to speak with law enforcement agents of any kind, and to decline to cooperate with grand juries. Likewise, it is now widely understood that posting sensitive information about others’ activities on public forums can be equivalent to informing to the authorities about them. Yet failing to take proper precautions to protect your devices, overestimating your rights, and answering questions from border officials can have similar consequences, enabling the state to obtain information about your political activities or your network.

United States Customs and Border Protection

The US border is among the most tightly controlled borders in the world. The other members of the so-called “five eyes” intelligence union—the UK, New Zealand, Australia, and Canada—employ similar measures. Countries like Saudi Arabia and Israel are also notorious for invasive and opportunistic security procedures.

United States Customs and Border Protection officials have little accountability to anyone; there are no checks or balances on their power to protect those who are not US citizens. Legally, they aren’t supposed to question, profile, or discriminate against visitors on religious, ethnic, or political grounds. But they most certainly do these things.

In 2019, USCBP officers detained an 18-year-old US citizen for 23 days in a Texas Border detention just for looking and acting too Latino—even after he presented an ID and a birth certificate. This was not even at the border, but inside the state, when the boy was driving north to a soccer camp. USCBP have power within 100 miles of any American border; this includes entire cities like New York City or San Francisco.

Dressing according to conventional standards may help to avoid extra attention and scrutiny when crossing borders. Police are often superficial and may judge by appearances if you are not already flagged. Of course, this will not necessarily help people of color and other targeted demographics.

US Citizens

If you are a US citizen, the most important thing to remember when entering the US is that unless you are arrested upon arrival, you will eventually be let in. Legally speaking, you have a right to enter the country regardless of your cooperation with interrogators.

If you are brought into an interrogation room upon arriving in the US and non-uniformed officers or officers without USCBP identification are present, you should immediately request that they identify themselves. If they are FBI agents or non-USCBP police, request an attorney immediately. Due to loopholes available to border enforcement, non-USCBP agents sometimes use the special status borders afford to listen in on interrogations and gather intelligence in ways that would be deemed unconstitutional in other contexts. However, if you have requested an attorney, they should leave the room or cease to question you. This is not guaranteed, but technically, they are supposed to do so.

The laws regarding whether you can have an attorney at the border as an American citizen are complicated. Officers will tell you that you are not entitled to an attorney, as the law is confusing on this subject.1 According to USCBP, you are not entitled to a lawyer during first or secondary screenings when entering the country. As a citizen, you are entitled to request a lawyer, but it is not certain they will cooperate with your request. If you anticipate serious harassment, you should arrange in advance for an attorney to be on call or even to meet you at the airport.

Requesting an attorney may cause USCBP officers to escalate their efforts to intimidate you, but it will also let them know that you are prepared to stand up for yourself. Never forget that whatever happens, you will eventually be let into the country. If you are arrested, you will be entitled to an attorney as soon as you have been taken into custody by non-USCBP.

As a US citizen, you have the right to remain silent throughout your detention by USCBP. In theory, this is the best strategy for dealing with these officers. However, this will almost certainly escalate the encounter; if you insist on refusing to answer any questions from the outset, you will probably be detained, searched, and interrogated at length. Therefore, in practice, it can be advisable to start with a different strategy.

The alternative is to remain polite and cooperative in response to requests for your documents and simple questions such as where you are coming from, then to politely decline to answer once the questions became invasive or political. You could explain “I’m choosing not to answer, as is my right as an American citizen.” If the questioning intensifies, answer, “On the advice of my lawyer, I’m not going to answer any such questions.” This is the best way to phrase your answer, as it sidesteps any questions about why you are choosing not to answer.

You may be asked for your Facebook, Instagram, or other social media profiles. If you have any profiles in your legal name, it is probably better not to lie about it, as being caught lying will escalate the situation. It is better simply to decline to answer the question. It is a good idea to delete all apps that can be used to access social media and all online history, so there is no evidence on any device with you. Remaining silent in response to invasive questioning may be stressful; the officers may attempt to intimidate or trick you into answering. However, if you have the privilege of citizenship, they cannot deny you entry. Remember, they are counting on your fear. It is the chief weapon they have against you.

Do your best to prepare your emotions and belongings ahead of any potential encounter. This may not be the time that you are detained and harassed, but it is essential to prepare yourself, your devices, and your possessions so that you will have no regrets later.

While crossing the border as a US citizen, do not forget that whatever happens, you have the right to re-entry. A little courage and patience will see you through.

https://twitter.com/HMAesq/status/1221312555014152192

Non-Citizens

If you are not a US citizen, you lack most of the rights described above. Essentially, USCBP can deny you entry without reason. If you are denied, it is possible to send a letter requesting the reason and a reversal of the decision.

You will likely be asked to provide a destination to border officials. The best answer is probably a hotel or the home of a person who is ostensibly a respectable, law-abiding citizen. Border officials may test you and ask for receipts or proof of a hotel reservation or the name and contact information of the people you will be visiting. They may also contact your hotel or host. You should also be prepared to answer questions regarding where you are coming from.

Stay calm. Don’t risk making jokes, even harmless ones. Sarcasm can lead to detention or escalation. Remain respectful even if they bully you or attempt to provoke you. There’s no humanity when it comes to USCBP officials, like police, they should be understood as puppets of the state and navigated with calculated and stoic communication.

You are not entitled to an attorney unless a non-CBP agent formally arrests you. You have very few rights as a non-citizen in this situation; essentially, USCBP can deny you entry on almost any grounds.

Border control agents are basically able to do as they wish; because they are a federal police force, they do not have to recognize state laws. For example, if you arrive as a non-citizen in Oregon or California, where marijuana is legal, and you admit to having smoked marijuana at any point in your life, USCBP agents can reject your entry on this basis alone. Hundreds of Canadian citizens have been turned away from the US border and banned from the US for admitting to smoking marijuana at some point in their life—in a country where it is legal.

Electronic Devices

On November 12, 2019, a federal judge in Boston ruled unconstitutional the search or seizure of devices belonging to international travelers without individualized suspicion. While groups such as CAIR, the ACLU, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation hailed it as a victory, it may not change things very much in practice. We should never place faith in the state’s alleged protection of our civil rights; we will always find ourselves in a state of permanent exception when it comes to the democratic discourse of state-sanctioned rights.

This ruling does not give a binding course for eliminating the practice of search and seizure. The category of “individual suspicion” is extremely broad, and USCBP officials are free to fabricate any reasons they require. In addition, the federal government has stated that the ruling will only apply to Boston International Airport, in the district where the ruling was issued. We should proceed on the assumption that the state may still seize our devices.

Whether or not you are a US citizen, if you do not cooperate in unlocking phones, laptops, or other devices when requested, the officers are permitted to seize them until they have broken your code and copied the contents.

Some would say traveling with no devices at all is the best solution. This is by far the safest way to travel across borders if you think your devices will likely be searched or seized. Unfortunately, this can be expensive and inconvenient, as well as potentially suspicious.

Your phone should always be locked and encrypted at all times. A good password can go a long way.2 If you are a US citizen, you can refuse requests to unlock your phone, and a strong password and encryption can help protect your phone if it is seized. Nonetheless, if they return your phone after seizing it, it is best to assume that the phone is compromised and replace it.

USCBP agents have been known to demand that travelers turn on their devices, allegedly to show that they are ordinary electronics rather than disguised objects of some other character, threatening to confiscate and destroy devices that could not be powered on. If you would comply with such a demand, arrive with enough battery charge to be able to do so.

If you are a non-citizen, refusing to unlock your device could result in border guards seizing it and denying you entry.

If you do bring a phone or other electronic device to a border crossing, it is a good idea to prepare it by removing any information or programs that would give the state access to your contacts or communications. This should only be understood as a means of harm reduction. We can’t be certain of the full capabilities the state has to investigate phones and other devices. Bringing no phone or device whatsoever is the only sure way to limit USCBP access.

Whatever you do, it is suggested that you do it at least 48 hours before arriving to the border. Even when you delete a file on your phone, it may not be immediately expunged. Some people whose phones and computers have been confiscated by USCBP have received them back with applications, messages, and contacts on them that they had deleted shortly before they were seized.

One option is to reset all of your devices to factory mode well before the time of crossing a border. However, this could also be grounds for suspicion, and may create challenges for non-citizens. Another option is to cleanse all sensitive material from your phone so you can open it if asked.

Manicuring your devices and your life for interrogation is challenging. It requires being able to identify and delete any information or contact information that would be of interest to the authorities. Considering that you cannot know for sure who or what may be of interest to them, it is better to approach this as a consent issue: if USCBP officials gain access to your phone, would all of the people in your contact list be comfortable with the state associating them with you?

Keeping the numbers of family members or non-political friends who consent to be associated with you in your phone when you approach a border might help to allay the suspicions of border officials if they ask you to unlock your phone and you choose to comply. Bear in mind that USCBP officers might contact someone at random from your list; ideally, anyone who answers should know to refer to you by your legal name alone, so as not to put additional information at their disposal.

If you open up your device for them, they could review all of your correspondence. If it is necessary for you to have access to a phone or device with sensitive information on it and you are a frequent traveler, another solution is to buy a phone or device for this specific purpose once you cross the border, or to keep a phone in each of your frequented destinations. If you choose to use a burner phone, there are some promotional plans that can be almost free with new activation.

USCBP shares information with a wide range of state agencies including the FBI. Whether or not you are a citizen, deleting sensitive contacts from your phone is essential to protect those who do not want their information shared with the US government. If you choose to open your phone when you have the contacts of anarchists or other targeted individuals in it, you are essentially cooperating with the US government at the expense of your revolutionary community.

In addition to deleting contact information, consider deleting applications for encrypted communication such as Signal or Telegram from your phone. When preparing your phone, you should make sure to delete all remnants of correspondence, downloads, and data that could be connected to the deleted contacts, history, and applications. This includes

-

email correspondence that offers an opportunity for state officials to fish through your information and compile a list of your contacts;

-

WiFi networks your phone has joined and learned;

-

photographs you have downloaded that include sensitive information or metadata;

-

and cookies that can be used against you or contradict answers you have given about your travels or plans, or that show that your phone has been manicured.

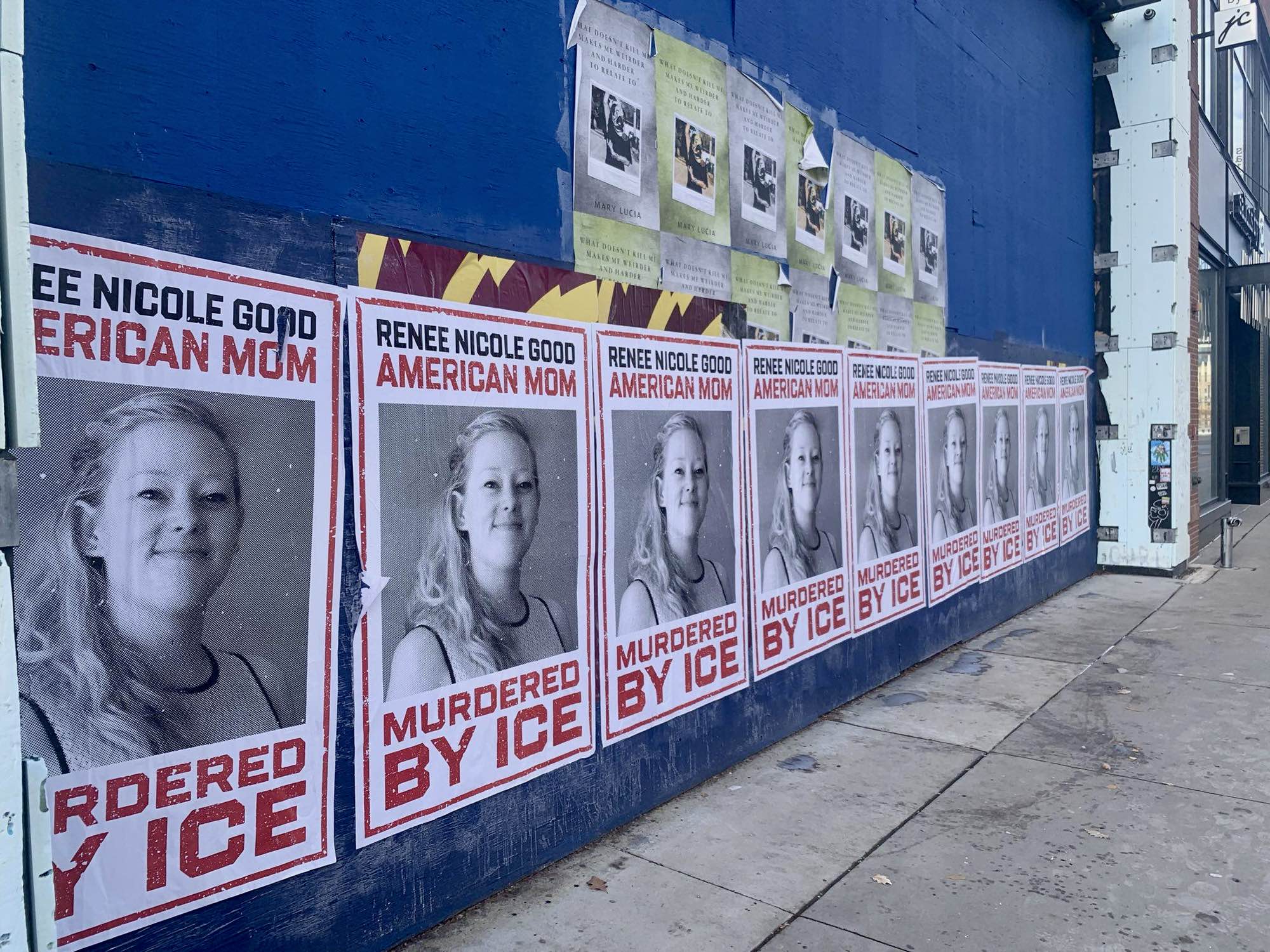

If you are a non-citizen, traveling with anarchist literature, posters, or books could also create grounds for officials to suspect you or deny you entry. For US citizens, traveling with such material will not enable them to deny you re-entry, though it could contribute to officials flagging you.

Regardless of your citizenship, if it is possible that you will choose to open your phone when asked, make it appear that you are using these devices in a normal manner and have nothing to hide. Open up new search histories, open some innocuous tabs on your browser, keep games on your devices, retain harmless correspondence and communication with those who are comfortable with you keeping their contacts in your phone, and keep some pictures or videos of yourself and your approved friends and family that don’t give away any sensitive details.

Regarding email and social media, if you claim that you do not use them, you must be very careful to ensure that all related history, downloads, and applications are cleared from all your devices. Some phones have Facebook built in, which offers an excuse; but if you have downloaded an image from Facebook and the authorities find it and analyze its properties, this could be grounds to accuse you of lying.

You can make secondary profiles, especially if you are a non-citizen and you are afraid that you will be rejected if you do not give officers access. Generally speaking, anarchists should not make social media in their legal names. There are many creative ways to avoid this. Likewise, you should never use a social media account can be traced back to your legal name for sensitive political projects or correspondence. As for email, it is easy to maintain a separate email for anarchist correspondence.

Social media creates tremendous security risks; it is a dismal part of social alienation, though unfortunately inescapable for many people. In any case, USCBP officers may search the internet for information about you, including social media profiles for you or any project you are involved in; you should be prepared to address anything they find.

You can upload contacts or files that you wish to keep private online ahead of any border crossing. You can export contacts into files and upload these into a draft file on a secure email forum such as protonmail.com or another safely hosted server, then download them to your manicured, stored, or newly purchased device when you arrive at your destination. It only takes minutes to make exportable contact files and folders.

It is safest not to discuss anything illegal on any electronic device, including via encrypted apps like Signal or servers such as protonmail.com.

Ideally, when you give your contact information to another person in the anarchist movement, they should be able to commit to making sure you are not setting yourself up for needless risk. Raids, unknown technologies, and unexpected arrests are among the threats that we face, but we should establish ethical frameworks and explicit expectations regarding how we conduct ourselves in order to minimize danger.

If you are detained or interrogated for specifically political reasons when entering or leaving the US, it is important to consult a lawyer and to report your experience to other members of your community. This is true following police raids or FBI visits; it is just as important following border crossings. Making a public statement online can enable you to reach a larger number of people, but it can also lead to an escalation by those harassing you, as they may perceive it to confirm their suspicions of your involvement in the anarchist movement. Whether you reach out publicly or on an individual basis, it is important to inform others in order to maintain a strong network of trust and transparency within our communities, to alert others who may be similarly targeted, and to battle tendencies towards isolation that can lead to people leaving the movement or even betraying other participants.

https://twitter.com/HMAesq/status/1221312557031608320

For Non-Citizens Applying to Appeal Rejection

If you are told you have been banned from entering the United States following rejection at a border, you can apply to repeal the decision via this application.

This is only for those who have been formally banned, not those denied entry. These applications are not reviewed by a judge or any independent authority, but a bureaucrat within the USCBP. Getting a ban lifted entitles you to nothing beyond the opportunity to try entering again. It puts you in the same position you were in before you were banned, but this time with a black mark on your record.

On the No-Fly and Terror Watch Lists

In 2014, the No-Fly list was deemed unconstitutional. In 2019, the Terror Watch list—which includes approximately 1.2 million people—was also deemed unconstitutional.3 Despite this ruling, no formal procedure has been established to dismantle the lists or stop the state from using them. How the list is produced remains a secret—ironically, this is one of the reasons it was deemed unconstitutional. So even if the courts have made this ruling, we should assume that both lists are still functioning as guides for the authorities. In both rulings, the people who challenged the lists did so on the grounds that they were law-abiding citizens who have been persecuted on account of being Muslim. In cases of political repression, we assume that the courts would extend little sympathy to any anarchist unlucky enough to end up on either of these lists.

Sadly, there is practically no way to challenge inclusion on the No-Fly list; you can only request the help of a lawyer and continue trying to fly. The ACLU has provided some guidance on challenging no-fly status here.

If you do not have a criminal record, it may be possible to travel overland to Canada and fly from there to your destination. However, depending on the degree to which you have been flagged, you may also experience harassment there, as the Canadian and US border control agencies share intelligence. You can also travel to Mexico overland in order to fly onward to your destination; you should be able to do so without having to report your visit for upwards of 48 hours after arrival. It may be possible to book a departure ticket for these first 48 hours in order to avoid using your passport.

If You Need to Travel Long term

If you need to travel for a long period of time, it is important to remember that under Obama, the US made it necessary to reapply for passport pages once you have run out of space for more stamps. If you run out of pages abroad, you can apply at an embassy. However, in case your travel needs turn out to be more complicated than those of a typical tourist, it is better to prepare in advance by getting a passport with 52 pages rather than 28. When acquiring a new passport, you can also order a Passport ID card. The ID card can serve as identification without disclosing an address and suffices for overland travel to Canada and Mexico. It can also help you to obtain a new passport if your passport is lost or stolen.

https://twitter.com/HMAesq/status/1221312561280421888

Further Reading and References:

“As those intrusions become more common and aggressive in the Trump era, WIRED has assembled the following advice from legal and security experts to preserve your digital privacy while crossing American borders. But take all of these strategies with caution: Given CBP’s unpredictable and in many areas undocumented practices, none of the experts WIRED spoke to claimed to have a privacy panacea for the American border.”

General Resources on Repression and Resistance

-

From an article in the Intercept:

“IN GENERAL, LAW enforcement agents have to get a warrant to search your electronic devices. That’s the gist of the 2014 Supreme Court case Riley v. California. But the Riley ruling only applies when the police arrest you. The Supreme Court has not yet decided whether the same protections apply to American citizens reentering the United States from abroad, and federal appeals courts have issued contradictory opinions. In the absence of a controlling legal authority, CBP goes by its own rules, namely CBP Directive No. 3340-049A, pursuant to which CBP can search any person’s device, at any time, for any reason, or for no reason at all. If you refuse to give up your password, CBP’s policy is to seize the device. The agency may use “external equipment” to crack the passcode, “not merely to gain access to the device, but to review, copy, and/or analyze its contents,” according to the directive. CBP can look for any kind of evidence, any kind of information, and can share what it finds with any other federal agency, so long as doing so is “consistent with applicable law and policy.” ↩

-

The strongest passwords are long yet easy to remember. A good rule of thumb is to select at least five random words. For example, “correct horse battery staple atom.” Include the spaces in your password—they give you extra length without making it harder to remember. The key to making your password more secure is length, not complexity; the previous example is much more secure than “ruvsybgj36,” provided the word selection really is random. Don’t come up with the words on your own; your brain may not be a good random generator. If you look around your room and make your password “curtain chair window sky,” that isn’t random. Instead, choose words randomly from a list like this one. ↩

-

Though the task ahead is weighty, with the judge essentially asking the two sides to settle a fundamental question of the post-9/11 era, CAIR is celebrating the ruling as a “complete victory.” ↩