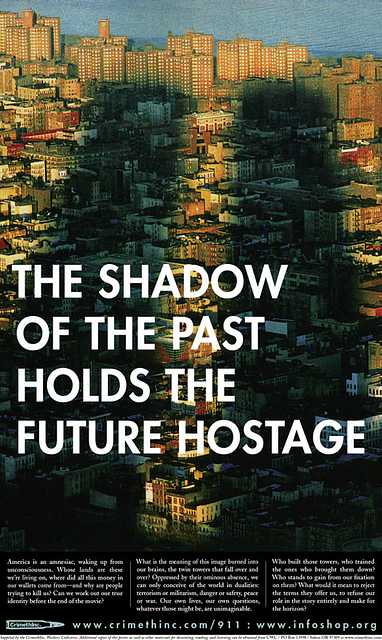

A large full-color poster printed on white book paper, made to be deployed in a variety of environments, from handing out at rallies or family reunions, or for use in decorating your dorm or cubicle— perhaps, just perhaps, even for wheatpasting! It uses a strong image (that coincidentally is a real photo, and not photoshopped) while the headline and body text pose questions that play on the emotional impact of the image. The back contains the essay Forget Terrorism: The Hijacking of Reality.

America is an amnesiac, waking up from unconsciousness. Whose lands are these we’re living on, where did all this money in our wallets come from—and why are people trying to kill us? Can we work out our true identity before the end of the movie?

What is the meaning of this image burned into our brains, the twin towers that fall over and over? Oppressed by their ominous absence, we can only conceive of the world in dualities: terrorism or militarism, danger or safety, peace or war. Our own lives, our own questions, whatever those might be, are unimaginable.

Who built those towers, who trained the ones who brought them down? Who stands to gain from our fixation on them? What would it mean to reject the terms they offer us, to refuse our role in the story entirely and make for the horizon?

A person who has a sense that her life is meaningful and her destiny is in her hands is in fundamental ways more alive than a person who does not. In that sense, on September 11, terrorists used airplanes to kill thousands of people, and politicians and media used the event to kill a little bit of everyone who survived.

Here’s one of those rare stories that gets the same spin from both the corporate and the independent media: there was a brief window of time between November 1999 and September 2001 when the most fundamental conflict in the world was between power and people. Up until the Berlin wall fell 1, it had been between capitalism and communism; now, as everyone knows, it’s between terrorism and so-called democracy. But for that brief, exhilarating period, the primary dichotomy in more and more people’s minds was between hierarchy and domination on the one hand and autonomy, liberty, and cooperation on the other.

Everywhere across the planet, people were starting to organize themselves, testing their hands at self-directed activities and pushing back when state and corporate interests tried to interfere. As summits of the economic elite were shut down, local collectives assembled, and global networks of resistance linked up, it began to feel like the future was up for grabs. But no one on either side of the barricades had factored in the unsettled accounts U.S. foreign policy had wrought in the third world, and everything changed the day terrorists, directed by a former employee of the C.I.A., brought those chickens home to roost in New York City.

Everyone knows the unutterable tragedy that occurred that morning, when thousands of human beings lost their lives in an act of cold-blooded violence. But another tragedy, a stranger, subtler one, compounded the first: the tragedy that occurs in this society when a large number of people have the misfortune of losing their lives live on international television.

An interesting side effect of the events of September 11 was that television news ratings shot through the roof. Everyone was glued to the television: and all conversations, in every city, state, and nation, were about New York City. Suddenly — because what one thinks about is one’s reality — New York City, and more specifically the attack and deaths, were the epicenter of reality, and the zones radiating outward from it were less and less real. The most a man in Iowa could hope for was to have a family member in the towers, so he could be connected by blood to the things that mattered. That, of course, is an insensitive overstatement — but let’s not deny that some of us who didn’t have such a relative felt a twinge of secret, perhaps subconscious jealousy of those who did, who could speak with such anguish and outrage about the one and only subject on anyone’s mind.

In the same way that serial killers and serial dramas, disaster movies and real disasters command attention, so did New York City: and everyone outside the city was paralyzed, looking on from a distance, wondering what would happen next as one does in a movie theater. We were all powerless, our sense of agency gone at the most urgent of times. Those of us who opposed corporate media and otherwise refused to be complicit in our own passivity still stared at the screen with everyone else; those who did not have such an analysis watched and accepted the conclusions of the talking heads as if they were their own. Later, doing as they were told, they raised a flag that was not their own, either.

So-called “activists” were among the ones most paralyzed, comparatively speaking. Those who had shared a sense that they could change the world now froze up as if hypnotized. This was certainly convenient for the powers that be, who scripted the coverage and spin of the tragedy — but why did this happen?

If you want to disable people, make them feel insignificant. Feeling insignificant paralyzes; without morale and momentum, all the power in the world — and remember, that power is made up of the assembled powers of all individuals, it is not some scepter wielded from above — can only be applied accidentally, according to the dictates of the few whose sense of entitlement is reinforced by their titles and television exposure. Feelings of insignificance render insignificant; desperation to be “where the action is” replaces the ability to decide for oneself what the action should be.

The underlying message of the news, the implication hammered deeper home with every replay of the towers collapsing, was that whatever we little people did, world history, and therefore real life, was out of our hands. The trivial little games activists and communities had been playing were irrelevant; no one would pay attention any longer, let alone join in. This was not necessarily true, of course. But it was news because it was on the news, and because it was news it made itself true.2

Ironically, this displacement of meaning — this centering of attention upon New York City as the global nucleus of meaning itself — was exactly what had outraged and baited the terrorists. But striking back at the heart of the empire with the same violence they had learned from it, they simply fed the beast — for whether you suffer it or apply it, terrorism is the ultimate spectator sport, and spectatorship can only consolidate power in the hands of the ones who direct the spotlight.

Those towers were not just a locus of financial power, but even more so of iconographic power — the most valuable currency in this information age. How is that kind of power gathered and reproduced? In the same way financial capital is gathered and reproduced: moguls centralize and monopolize it by impoverishing others of the sense that their life has meaning, thus forcing them to buy in to their mass-produced meanings. For example: people in small town America watch television instead of talking with each other, just as indigenous peoples outside the U.S. seek sweatshop employment, because it seems to be the only game town. This isn’t natural — for the mass-manufactured alternatives to appear desirable, those television watchers have to have lost the intimate connections and ongoing projects that would have brought them together off their couches, just as the natives have to have had their traditional life ways destroyed by conquistadors. Disneyland is as fun as Des Moines is dull, just as Michael Jordan is as rich as a Nike sweatshop worker is poor — these are not coincidences. Economic exploitation and media domination are essentially the same process, carried out on different levels.

So in terms of the war for sense of self that has gone on between us and mass media for generations now, September 11th, 2001 saw an act of superlative terrorism carried out against every one of us: not just in the hijacking and crashing of the planes, but in the way the event was used to hijack and crash the budding sense that we could determine reality for ourselves. This consolidated power in the hands of the U.S. government, among others, who used it to further paralyze and distract people by starting a series of controversial wars.3 In a time when the hierarchical elite was anxious to come up with a new false dichotomy to distract everyone from the fundamental struggle between power and people, nothing could have been more opportune.

The question, now — the ultimate question, on which all life hinges — is how we can once more reframe the terms of this conflict. It is not a question merely of peace versus war: the decade of “peace” that led up to the September 11 attacks was sufficiently bloody to persuade a generation of suicide bombers that it was worth dying to get revenge on the West, and a new peace under the current conditions would be even more treacherous. Nor can we cast this as a conflict between ideologies: we cannot afford to be armchair quarterbacks any longer, backing our favored teams or themes against others while bullets and bombs rain randomly into the stands. The question is — always is, no matter who is dying or killing, no matter what is said on television — what we can do ourselves, what we make of our lives, how each of us interacts with global events in our daily decisions. Our opponents are those who would hinder our efforts and obscure this question for their own ends, who would rather rule over a world of passive spectators wracked by terror and war than take a place among equals acting to correct the injustices that provide justifications for politicians and terrorists alike.

Everyone knows, if it were up to us there would be no more wars, no more exploitation, no more terrorism. It is up to us.

CrimethInc. Workers’ Collective, election year 2004

-

History is rife with ironic coincidences, not the least of which being that the Berlin wall fell on 11/9. ↩

-

This shows how much we’ll have to learn about being able to ignore the media, if we are to build a sustainable liberation movement. ↩

-

As Hitler said, if you want to keep soldiers from stopping to think for themselves, keep your armies marching — and that goes for liberal protesters as well as army recruits. ↩