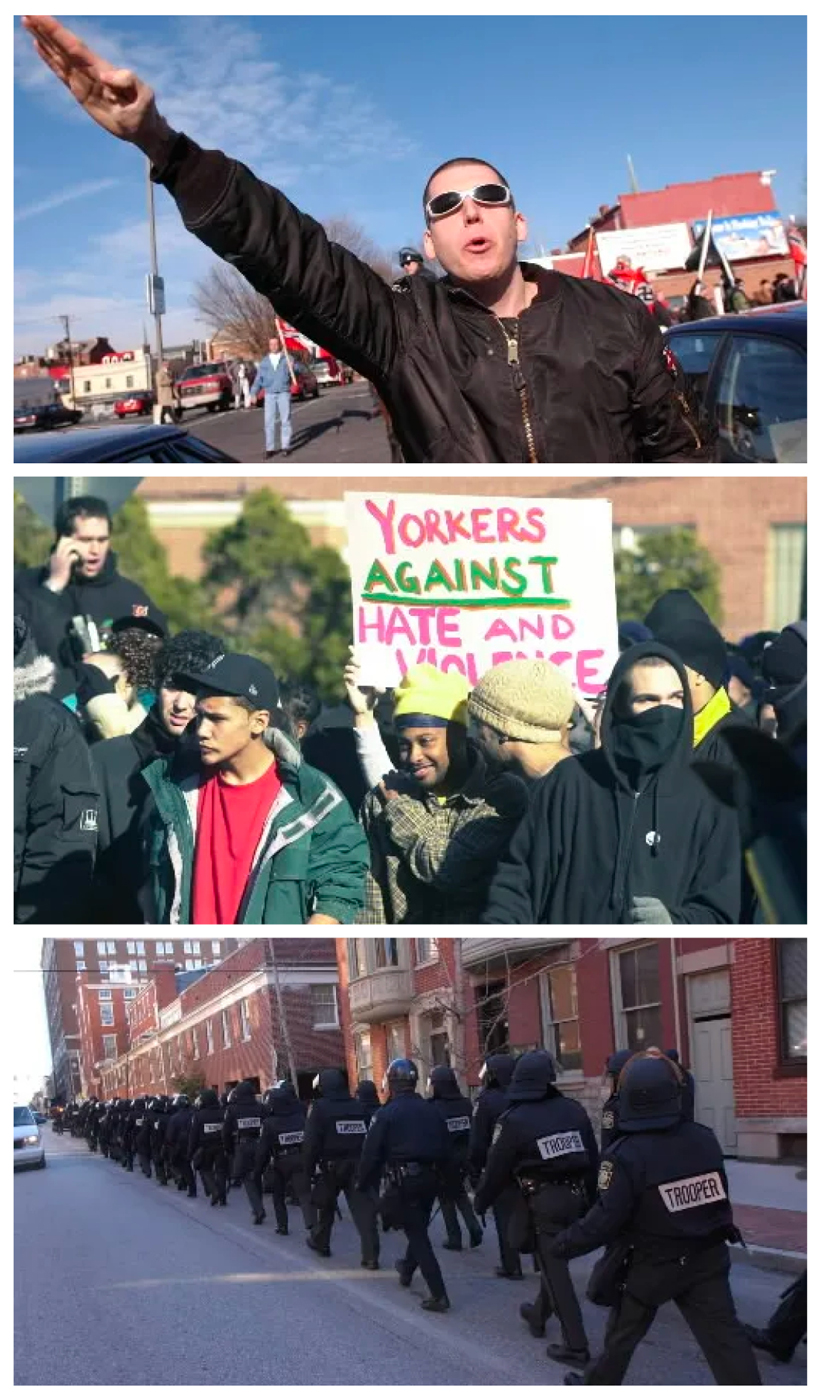

On Saturday, January 12, 2002, hundreds of neo-Nazis gathered in York, Pennsylvania to promote white supremacy. Anarchists and other opponents of fascism throughout the region mobilized to prevent them from achieving their purpose.

As usual, the police did everything they could to protect the neo-Nazis. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, officers arrested 25 people, “all but two of them anti-racists.” Nevertheless, the anti-fascists made common cause with locals and sent the fascists packing from York.

Twenty-one years later, a participant in the battle of York recounts the clashes of that day and reflects on what has changed since then, comparing the events in York with those in Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017.

The following account is adapted from a forthcoming memoir on PM Press, entitled The Anarchist International. You can read more from the same author here.

The Gathering Storm

It was the year 2002 and I was in an anarchist organization. The attacks of September 11, 2001 four months earlier had put a damper on many of the movements we had participated in, clearing the way for jingoistic patriotism and warmongering. Nonetheless—for precisely that reason—we were determined to continue our efforts at full throttle.

One of our focuses was combatting fascist organizing. Our print publication, Barricada, was militantly and vocally anti-fascist. We regularly mobilized against fascist rallies and events. We included a “Bloody Nazi of the Month” picture section in our publication, in which we outed the names, addresses, and license plates of fascists.

The Nazis were hailing their upcoming gathering in York, Pennsylvania as a “great unifying rally,” with confirmed attendance from the infamously violent Eastern Hammerskins as well as the two leading racist organizations of that time, the National Alliance and the World Church of the Creator. They had called for a rally and a public meeting at the city library in York because the city was embroiled in a controversy regarding the involvement of Mayor Charles Robertson in a 1969 race riot that had culminated in the death of a young Black woman at the hands of a white mob. Robertson, who had been a police officer in 1969, had finally been arrested and charged with her murder. Despite the arrest and charges, Mr. Robertson refused to resign, outraging York’s African-American community. The white supremacists were rallying to his defense, and Matthew Hale, leader of the World Church of the Creator, was to be the “keynote speaker.”

By 2002, Matt Hale and his organization, the World Church of the Creator, had been growing steadily for several years. Hale had appeared in several television interviews, where he could be seen wiping his feet with an Israeli flag as he entered his home, proclaiming himself Pontificus Maximus [sic] of his “church,” and promoting “The White Man’s Bible,” calling for “rahowa,” short for “Racial Holy War.” Their flag was red with a white circle in the middle bearing a “W” instead of a swastika.

Today, Matthew Hale is serving a 40-year prison sentence for attempting to solicit an undercover FBI informant to murder a federal judge. His organization has been superseded by a series of other such groups. But in 2002, anti-fascists had to take him and the World Church of the Creator seriously alongside the National Alliance, another of the most dangerous fascist organizations of that time.

We had already had the pleasure of meeting some of these fine representatives of the Aryan race a few months earlier in Wallingford, Connecticut. In fact, the mobilization to counter their public meeting at the Wallingford Public Library had been so successful that many people were skeptical that it would be possible to accomplish much in terms of direct confrontation in York. A small contingent of primarily Boston anti-fascists had mobilized to Wallingford; upon arriving at the library, they were pleasantly surprised to see that the police had failed to create any kind of physical division between the Nazis who had assembled outside and the growing crowd of anti-fascist protestors. Afterwards, we hypothesized that this was due to the fact that the New England area had experienced a lull in public fascist organizing, so local police were unprepared for militant anti-fascist opposition, black blocs at that time being largely reserved for summits and party conventions.

The Hartford Courant described the events:

1:30 p.m. — A large group of protesters surges into the parking lot. Many have scarves and handkerchiefs covering their faces.

“Racist, sexist, anti-gay! Matt Hale, go away!” they chant. A young man briefly tussles with a Hale supporter. A police officer reaches in. “Hey, watch it! Watch it!” the cop yells.

[…]

Many of the protesters are college students. They carry signs that read “Racial harmony not racial holy war.” They are from Boston, Washington, and Philadelphia. Some are members of the Connecticut Global Action Network, which also organized during the Seattle protests against the World Bank last fall. Another group of activists from Boston describes itself as “an anarchist collective.

“Large” was a generous descriptor; the bloc numbered somewhere between 25 and 40 people. As the cops watched this small but tight-knit black bloc advance swiftly towards the racists holding neo-Nazi and confederate flags, they remained surprisingly passive. Never inclined to look a gift horse in the mouth, the anti-fascists quickly charged the racists. The ensuing brief but lively confrontation resulted in the Nazis losing several flags and gaining a few injuries. Police eventually intervened with pepper spray to break up the mêlée, rescuing the “Pontificus Maximus” in the back of a police cruiser.

Matthew Hale returned to Wallingford a month later. This time, those who turned out to oppose him faced a radically different scenario. Despite the New York Times and other outlets reporting that there had been only “minor scuffles,” police had no desire to lose control again. This time, as one reporter put it, “police preparations that were made days ahead of time—including dug-in telephone pole barricades and blocks of concrete the size of cars—kept Hale supporters and protesters apart.”

If memory serves, I believe there were police officers armed with pepper ball guns mounted on elevated platforms along the perimeter of the barricades.

Flanked by neo-Nazis, Matthew Hale awaits instructions from his chief protectors, the police, in Wallingford, Connecticut on April 21, 2001.

On the Prowl: Saturday, January 12, 2002

We organized in a network of perhaps 50 or 60 comrades, mostly comprised of anti-fascists from Columbus, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, DC. We ourselves had coordinated privately beforehand in a tight-knit group, primarily consisting of NEFAC [Northeastern Federation of Anarcho-Communists] and ARA [Anti-Racist Action] groups. We saw these joint mobilizations as an opportunity to work with others outside our immediate circles in order to build an anarchist fighting force that could mobilize swiftly and discreetly.

We had just stepped out of the strip mall parking lot that we had chosen as our meeting point and into the outskirts of York when somebody yelled out, “Oh shit, look at that truck!”

We couldn’t believe our eyes. There was a red pickup truck about 30 meters away from us, like any other except for the distinctive decal on its rear bumper: the upside-down peace sign of the National Alliance. As we began to move towards them, the Nazis yelled something and sped off, tires screeching dramatically as they made their escape. A few of us made commendable yet futile attempts to reach the truck as they ran the light. Sadly, no amount of youth, training, enthusiasm, or political analysis can enable you to match the speed of an automobile on foot.

We had just resigned ourselves to this when the red pickup truck reappeared, having apparently circled the block. Just then, the light at the corner turned red, trapping the Nazis between other stopped vehicles! Five or six of us sprinted toward them once more. Glass shattered and the inside of the truck was generously doused with pepper spray.

Barricada describes the ensuing confrontation thus:

“At this point, the two Nazis, the bravest of the day, decided to jump out of the car and confront the crowd, the driver wielding a baton in his hand. As he faced off with one anti-fascist, others circled around him and attacked his car from the front. At one point, however, taking advantage of a distraction, the driver jumped back into his vehicle and sped away, leaving his passenger to dive into the back of the pickup already in motion (a true “Great Moments in White Pride” scene). The driver of the truck was later identified as Jeff Omasta, of Edgewood, Maryland.”

This skirmish, while emboldening, also drew us a police escort, in the form of a squad of riot cops on foot. They didn’t seem to be seeking a confrontation, nor did they appear to have any intention of carrying out arrests. They consistently kept a distance of a half block or more. We deduced that their objective was to keep us out of York’s inner city and away from the library.

Being tight-knit and well-organized, we managed to outmaneuver and outrun them. With the cops between us and the library, we marched the other direction, then turned and moved as fast as possible down the next parallel street back toward the city. The cops figured out what we were doing and tried to cut us off at the next intersection, but it was too late.

A preacher was loudly preaching “the white man’s gospel” at the police barricade in front of the city library. He was waving a copy of “The White Man’s Bible” around, the way a regular bible thumper might brandish the Good Book. He kept on yelling right in front of a wall of cops as a mob of black-clad masked anti-fascists approached him.

The York Daily Record describes the scene:

The anarchists wound up at the intersection of East Market and Duke streets, where police had erected a barricade. As they milled in the street, a man who said his name was John King and identified himself as a World Church of the Creator member from Virginia held up a copy of the church’s holy book, “The White Man’s Bible,” and taunted the anarchists… One of the protesters snatched his book and threw it in the street.

“Can I have my book back?” King asked. He looked at several police officers nearby for help, but they responded with a look that said King was on his own.”

Indeed, without word or violence but in plain view of the cops, I had relieved him of his “bible.” The cover promised it to be “a powerful religious creed and program for the survival, expansion, and advancement of the white race.” A must-read for an inquisitive Jew such as myself!

He began yelling to the cops that he had been robbed. The newspaper, while wrong about the “bible” being tossed into the street, is indeed correct that none of them intervened. We took note of this: it was the second indication of the day that they were not keen on a confrontation. I tucked the book inside my jacket and schlepped it with me all day rather than doing the safe thing and throwing it into the nearest garbage can. You could blame the football hooligan culture I grew up around for the “trophy hunter” mentality, but displaying of confiscated fascist propaganda after the fact sends a powerful message to both friend and foe alike. I consider it a valid political tool.

Neo-Nazis waving German battle flags in York on January 12, 2002.

Once we had reached the vicinity of the library, after the incident with the preacher, there were a few minutes of aimless milling around as we discussed what our next steps should be, as we assumed most Nazis were probably already inside the building. At this point, a group of three men caught our attention. They were youngish, probably late twenties or so, muscular build, short cropped hair, no distinguishing patches or visible tattoos, one of them wearing a bomber jacket, all of them eyeing us suspiciously. After a bit of hesitation, they began moving towards the police barricades in order to enter the library.

Being the inquisitive and friendly kids that we were, we thought it would be proper to have a quick chat with them first.

“Hey hey hey, what’s the rush?”

“Are you a Nazi?”

“Are you looking for your friends inside?”

We asked the basic icebreakers while blocking the way. All the attention and questions must have made them a little shy, because they didn’t seem to want to chat with us. Suddenly, one of the comrades lost patience—frustrated with their lack of social skills, no doubt—and a flagpole struck the head of one of them with a loud “crack.”

In that instant, one of them whipped around while putting his hand in his jacket. I distinctly remember thinking “Oh shit, gun.” Maybe the comrade with the bulletproof vest hadn’t been exaggerating about the risk. This was Pennsylvania, after all.

Then we realized that the shiny metal object in his hand wasn’t a gun—it was a police badge! Oops. Honestly, I wasn’t sure which was worse. It was a cartoonishly comical moment as all of us who were a split second behind the quick-drawing comrade with the flagpole strike to the head turned away mid-movement like vampires who had just been flashed a cross. Not our finest “Let’s try to not antagonize the cops too much today” moment. But somehow, miraculously, without further consequence.

Still, seeing as how the Nazis were already inside, the area was full of cops, and it probably wasn’t a great strategy to whack cops over the head with blunt objects and then hang around to see what happened next, we decided that was probably our cue to move along. Our time around the library had also allowed some stragglers and unorganized groups to join the bloc. There were now closer to a hundred of us. We decided to march around the area looking for stray Nazis.

“What are those flags?” A friend from DC pointed to the end of the next block ahead of us. In the distance, we could see several flags, mostly bearing red and black colors. My comrade turned to one of the anti-fascists from Philadelphia: “Are we missing anybody?”

“I don’t think so, all the groups are accounted for. And if it were just individuals, there wouldn’t be that many and they wouldn’t have all those flags.”

As we approached, we got a clearer look. They were not red and black flags, but rather red, black, and white…

Then the swastikas came into view.

According to the Barricada article, “Victory in York,”

“We had accidentally stumbled upon a parking lot full of Hammerskins. Almost immediately, the bloc broke out into a run in order to reach the thirty or forty Hammerskins before the police could rush in to save them. However, the few moments of hesitation were enough to allow the police to set up a dividing line between the Hammerskins and the anti-fascists.”

Perhaps some of the US comrades were more accustomed to this, but for me, as a foreigner, it was a shocking sight. I had seen a swastika here or there in other countries, in photographs of clandestine Nazi shows or on some bonehead’s patch or tattoo. But since they are illegal throughout Europe and South America, I had never in my life witnessed a group of Nazis standing in the street with enormous swastika flags. They looked like real-life incarnations of the cartoon cliché of a Nazi bonehead, uniformly sporting shaved heads, bomber jackets, and steel-toed boots.

As a militant anti-fascist with an intellectual understanding of the past horrors of fascism and the dangers that it currently poses, I have made fighting fascists a more or less central aspect of my adult life. But I am also the grandson of Jewish refugees from Germany. I grew up on the stories my grandfather told me about not being allowed to ride the train to school because he was not “Aryan,” about the yellow star he had to wear. His father, my own great grandfather, was a decorated German soldier who had been wounded in World War I. They were fully assimilated Germans first, Jewish second. My grandfather told me that his father, this veteran of war, could not bring himself to understand that “his” country would turn on them like that, that they were no longer “German” but “other,” just “Jews.” In 1937, after my grandfather received a particularly vicious beating from a group of Hitler Youth, my great grandfather finally decided to take his family to Paraguay.

So my antifascism is practical and personal as well as intellectual. The sight of a swastika-waving mob standing smugly behind the shelter of a police line inspired a visceral rage that to this day I don’t feel I can adequately articulate.

But as far as I could tell, we had reached an impasse. The police were between us, protecting the Nazis.

The three forces on the streets of York on January 12, 2002: neo-Nazis, locals and anti-fascists intent on confronting them, and police determined to protect the Nazis so they could recruit with impunity.

The Battle of York

“Hey, are you seeing all these people?!”

I turned to the person asking, a friend from the Midwest with whom I had shared more than a few scenes of combat with over the preceding year. Sometimes, you lose the forest for the trees; I had been staring at the swastika enthusiasts for the last hour or so, losing track of the rest of my surroundings. When I finally turned to look behind me, I saw a sight as surprising as it was inspiring. Whereas previously, we had been a group of less than one hundred black bloc anarchists, we were now part of a crowd of perhaps five hundred people. There were people of all ages—some white, but mostly Black and Latino/Latina. People in the neighborhood had heard what was going on and had come out to see for themselves.

She and I started to mingle with the crowd. A lot of them were not sure what to make of the mob of weird kids in ski masks. We engaged in conversation where we could. Whether because she was a woman or simply because she was friendly and articulate, most people seemed to be more inclined to engage with her. For my part, I made a point of talking with those I heard speaking Spanish. From our interactions as well as from the snippets of conversations we caught among locals, it was clear that word was getting around to the effect that the people in black were the good guys and gals.

“Up the street, Louise McCarthy, a legal assistant, watched warily from her stoop. She thought the white supremacists should have met in the square—”out in the open”—instead of in the library. A passerby told McCarthy he hoped there wouldn’t be any trouble. McCarthy responded: “I hope (the protesters) beat the s— out of them.”

Another conversation captured by the increasingly incredulous York Daily Record reporter went similarly: “That’s the good crowd. They’re going stand up to those people. I appreciate that.”

I don’t remember a single conversation or incident that day involving concerns about protecting the free speech of Nazis, or the idea that violence would make us just as bad as the Nazis, or any other liberal horseshoe-theory-of-extremism nonsense. This was a multi-racial working-class neighborhood and the mood was combative: Nazis out! That would have been enough to make for an inspiring experience, with the headline in next month’s Barricada declaring “Local Community and Anarchists Confront Nazis; Nazis Cower Behind Police Protection.” But it would have ended there, had it not been for the energy and initiative of the local youth.

It’s important not to repeat white racist tropes depicting young people of color as inherently dangerous. Those pave the way for racist vigilantes to stalk and murder youth of color on the streets when they try to purchase Skittles or go jogging. At the same time, it’s fair to say that some of the young people who joined us that day were no strangers to violence.

At first, there was a small group of five or ten. They started calling their friends, and before we knew it, a solid forty to fifty combative locals, mostly in their teens or early twenties, had gathered alongside us.

As if on cue, either the Nazis or the cops decided it was time to go and they both began moving up the street and into an alleyway leading to the parking lot. This generated excitement and commotion, but there was still a solid police line separating us. The locals proposed a solution: “This way, this way! We can get into that alleyway from the other side!” We sprinted along behind them, a hundred people strong. Within seconds, we were face to face with the Nazis, who had no cops to protect them this time.

The ensuing confrontation was intense. Boots, fists, and flagpoles flew in every direction. The police swiftly intervened, but not before several Nazis received bloody noses and someone on our side suffered a broken elbow.

A neo-Nazi bloodied by anti-fascists in York, Pennsylvania on January 12, 2002, along with coverage of the day’s events from the New York Times.

As we withdrew before the ensuing police charge, I saw my comrade stumble as a police officer caught up with him. It seemed to me that the officer had the upper hand—but at the last minute, my friend regained his footing and sped away.

“Dude, when we were on the ground, you know what that cop said to me? ‘Go, go, go, get out of here.’” Evidently, at least some of the cops had decided that we were the lesser of the two evils that day.

We regrouped and got our bearings. We still numbered a good fifty or sixty. The Hammerskins were in the street, while the cops had pushed us back into the open-air parking lot… the parking lot full of the Nazis’ vehicles! If only they could see the grins beneath our ski masks. We began playing an energetic adaptation of“Where’s Waldo?”—Spot the Nazi’s car and remove the windows. The merry music of smashing glass resounded in the parking lot while the Nazis watched helplessly from the street.

From the Barricada article “Victory in York”:

Eventually, the police decided to try to usher the Hammerskins out through the other side of the alley, halfway down the intersecting street. Once again, the local youths led the way at full speed and directed the out-of-town anti-fascists to the exact spot where the Nazis were to be found, once again, without police to defend them. Several dozen Hammerskins with swastika flags, and one in a white pickup truck, faced off against a significantly larger number of black bloc anarchists and local African-American and Latino youths. After instants of hesitation, during which all sorts of debris flew, the anti-fascists charged full speed into the Hammerskins who, in another display of “White Pride and Bravery,” retreated quickly behind police lines, losing a large swastika flag in the process.

The confrontation was extremely violent and, for lack of a better word, intimate. The setting, an urban alleyway, had a kind of modern day West Side Story charm. We were in hand-to-hand combat. On both sides, you could see people nursing injuries, visibly bloodied, although the Nazis definitely got the worst of it.

I would be lying if I said that I feared for my safety at the time. I wasn’t thinking about any such thing. But there is a significant distinction between a confrontation with the repressive arm of the state and a confrontation with fascists. In a street confrontation, while a police officer will usually respond within certain parameters and protocols of engagement, this is not the case with fascists. If you are at a demonstration and push against a line of police, the chances are slim that one of them will pull out a knife and stab you in the heart. This is not the case with fascists, who can and will kill you.

But the inverse is true, as well. When we engage in confrontations with police, because our tax dollars have paid for tons of expensive protective gear for them, the chances of inflicting serious injury are relatively slim. Moreover, at least in my case, my opposition to the cop is based on the mercenary role he plays perpetuating capitalism and the state. From my perspective, the individual cop is not necessarily a hateful villain. I am fighting what he is paid to defend, not necessarily him as an individual.

This is not true of the fascist. As an individual, the fascist is my enemy. He is a bigot with ideas that are diametrically opposed to mine. His victory means danger and death to vulnerable, marginalized, and excluded communities and individuals. It means danger and death to me personally as a Jewish person. There is nothing ritualized or symbolic about our confrontations with fascists.

I take great pride in my role in standing up to violent racists, that day in York and elsewhere around the globe. In that clash, I became the proud owner of a swastika flag to go with my “White Man’s Bible.” Some Nazi tried to hit me with his flagpole, foolishly using the side with the flag on it as the business end of the weapon, and was promptly relieved of both flag and flagpole. If ever you must use a flagpole with a flag on it as a weapon, wrap the flag tight around it and strike with non-flag side towards your opponent.

But ideally, don’t use flagpoles as weapons. Try to resolve your differences amicably. Violence is bad.

Neo-Nazis and police officers, some of them on horseback, attack York locals responding to the invasion of their community on June 12, 2002.

We live in a world that is structured around the threat of violence, implicit or explicit. It is not surprising that attempts to change the world often lead to violent confrontations. It should also not be surprising if these are necessary when it comes to opposing the adherents of genocidal ideologies.

Which brings us to the next point that often comes up in regards to confrontations with Nazis—the issue of fear. Those who applauded what we did but who didn’t feel capable of doing it themselves sometimes described us as “brave.” I can’t speak for others, but in my case, this notion of “bravery” didn’t apply to me. I understand bravery as taking action despite fear. But whether because of my personality, my political fanaticism, or for some other reason, I felt no fear for my own well-being. Somehow, the idea that I could be significantly injured or even killed in a confrontation never crossed my mind, despite my having seen several comrades fall. In my eyes, I was simply taking my convictions to their natural—and to me obligatory—conclusion, using my body as a tool against fascists, state, and capital.

What happened next shocks me more today than it did back then, now that I am a little older and a lot more appreciative of the fragility of human life. And I can no longer think of York without thinking of Charlottesville and what happened to Heather Heyer.

Whether panicking or simply seizing the opportunity to murder people he considered less than human, the Nazi in the aforementioned white pickup truck hit the gas, driving into the crowd at full speed. As in Charlottesville, where people were penned in by the cars parked on both sides of the road, we were penned in the alleyway, with nothing but wall to either side of us. My comrades and I were fortunate enough to dodge the oncoming truck, but one anti-fascist was not. Incredibly, he suffered nothing more than a dislocated shoulder.

The Nazi also struck a twelve-year-old local girl. She required hospitalization to treat her injuries, but miraculously, she escaped permanent physical injury.

From an anonymous street medic’s eyewitness account:

Then I heard somebody scream, “MEDIC!” I went back into the insanity behind me to find that a girl around I would assume was 10-14 years old had been sideswiped by the truck that had minutes before been driven through the crowd. Another medic on the scene was doing what little she could for the girl, such as keeping her calm and treating for shock, as I dialed 911 on my cell phone. I was put through to the dispatcher and requested EMT backup and an ambulance. Waiting for the ambulance to arrive, we were approached by around 20 riot cops who proceeded to harass us, asking us what we were doing there. We told them that we were medics, but they continued to harass us. An unidentified woman who knew the girl who was hit (I don’t know if the woman was her mother or aunt or just a friend) was standing up against a building behind the injured girl, screaming at the police, asking how they could let this happen. The ambulance then drove up and a medic got out and began to check the injured girl. The cops grabbed the screaming woman as the medic was working on the girl and the cops started a fight right over the girl who had been hit by the truck. As the woman fought back, several black bloc members rushed the cops and attempted to pull them off. One of the black bloc members in a valiant attempt to free the woman tackled a cop and was then grabbed by three other riot officers. As they pinned him down and got the cuffs out, the cops were hit again, and the bloc member was yanked up and flung into the crowd and disappeared. Watching this, it was then that I noticed the ambulance fleeing the scene. Everyone was screaming at them because they left the girl at the scene.

Imagine if that little girl had been killed. Obviously, a rational analysis would have us conclude that the responsibility lay squarely with the homicidal Nazi who saw a bunch of anarchists and a young Black girl and decided to treat them like bowling pins. But to what extent would we have been indirectly responsible for contributing to the situation?

The Nazi’s truck stalled about half a block down the road. Once again, people attacked him. He lost all his windows, and then as he continued trying to flee he struck both a police officer and his vehicle. The cop gave him quite a beating before proceeding to arrest him. (Baltimore Nazi Richard Desper’s terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day ended with four counts of aggravated assault and one count of reckless driving.)

That was the point at which things started to get insane. The cops completely lost control of the situation, as several groups of ten to twenty people hunted Nazis around the city as they tried to make their escape.

Our group quickly encountered yet another white pickup truck (apparently the racists’ vehicle of choice) with a bonehead girl wearing a Skrewdriver scarf standing by it. Skrewdriver was the band led by the late Ian Stuart, who rose to international fame among racist youth thanks to catchy and poetic masterpieces such as “White Power,” “White Warriors,” “Race and Nation,” and “Blood and Honor” In 1993, Mr. Stuart was fatally attacked by a tree while driving, in yet another heinous act of anti-white racism.

One of us unsuccessfully attempted to relieve her of her scarf. She scrambled into the passenger’s side of the truck. A flagpole came crashing down on her hand as she closed the door. The driver sped away, but stopped less than half a block away.

Again, all the windows were smashed. One of the local kids grabbed the driver with both hands and tried to pull him out the window of the truck. Failing that, he proceeded to strike him repeatedly. I moved around to the passenger side, thrusting half my body through the window. And this is where I probably should have died.

The next image in my mind is that of a handgun pressed firmly against my masked forehead. The driver had recovered and was looking straight at me while pressing the gun against my face. In that moment, my only reaction was to call out “Gun!” in order to give my comrades fair warning. I pushed myself back out of the cab, then proceeded to attack again, but from the rear window, trying to stay out of view and ideally out of the way of a possible shot. Somehow, the idea that I was in potentially mortal danger didn’t even cross my mind, although I reflected that the comrade who had worn a bulletproof vest might not have been overprepared after all. Aside from that, the incident did nothing to make us think that “Hey, maybe that was enough for today.”

On the contrary. We continued ambushing cars and trucks full of racists around the city. The only explanation I can come up with as to why neither I nor any of my comrades were shot that day is that the racist right have gained confidence and combativeness over the two decades since.

Anti-fascists attack neo-Nazis driving a truck in York, Pennsylvania on January 12, 2002.

After the gun incident, our next encounter was with a van full of World Church of the Creator “White Berets,” the so-called defense forces of the WCOTC. They briefly exited the vehicle as if to confront us, then jumped right back in and sped off as the van’s windshield caved in. I can’t possibly imagine that these people were not armed, yet they didn’t even brandish a firearm as a dissuasive measure.

The Nazis we fought at York were representatives of the largest and most violent fascist organizations of that time. To us, York was a momentous battle. A gathering of well over a hundred Nazis in the Northeast was an exceptional and worrying event, but it ended with them being run out of the city.

Yet when I look at footage from Charlottesville, I can’t avoid the conclusion that our enemy at York was almost harmless compared to the fascists who gathered in Charlottesville in 2017. I’ve been involved in anti-fascism for over twenty years and on three continents, including a ten-year stint in Germany where there are indeed a large number of fascists. But what I saw in Charlottesville terrified me.

Besides the issue of numbers—as the gathering in Charlottesville was significantly larger than the one in York—the main distinction is in the confidence of the fascists and how common it has become among them not only to brandish firearms, but also to use them offensively. Their movement has normalized the mass murder of those who don’t fit into their vision of a white ethno-state—not just as fantasy, but in tangible acts, as evidenced by the regularity of white supremacist killing sprees, now indubitably the most significant “domestic terror” threat in the United States.

In the decade and a half between the fascist rallies in York and Charlottesville, fascists successfully regrouped and rebranded, emboldened beyond their wildest dreams by the political developments of those years—including a president who acted as their cheerleader-in-chief.

The white supremacist lunatic fringe of the 1990s and early 2000s seems to have effectively merged with the much larger and politically powerful movement of “white grievance.” White grievance and the conscious or subconscious defense of whiteness as a dominant force in society was the driving force behind Trump’s appeal. Capitalism has exacerbated this, as declining economic conditions leave white workers more susceptible to a reactionary analysis, and the failure of the “left” to fill that void doesn’t help. But the experience of racial privilege and the fear of losing it remains a driving force in the reactionary drift in US society.

Organized white supremacists have been effectively harnessing that sentiment and positioning themselves as faithful vanguard of Trumpism. They may be relatively few in number, but they are filling several key roles. They are its shock troops on the streets—but just as significantly, they are the main driving force behind attempts to normalize the racist attitudes that had begun to shift to the margins of society thanks to decades of anti-racist struggle. The backlash against “political correctness” represents an attempt to re-legitimize racist, sexist, homophobic, anti-Semitic, and reactionary attitudes and language that had been successfully marginalized through decades of struggle.

I don’t have a particular solution to propose. Far from it. I hated the “veteran of battles past gives lessons to youth” speeches when old-timers subjected us to them. If anything, I would simply make a broad argument for the continued urgency and necessity of militant anti-fascism on all fronts. I would also encourage and applaud efforts to improve our training and capacity for collective defense, so that we can deny the fascists any easy victories and keep ourselves safe at the same time. As a comrade pointed out to me after York, “We may be the good guys, but we aren’t bulletproof.”

Anarchists in York, January 12, 2002. Members of the Anti-Racist Action chapter in Aurora, Illinois made business cards featuring this photograph.

We drove away from York that day feeling powerful, happy, and emboldened. It didn’t hurt that we had a nine-hour drive during which to rehash every detail of what we had just experienced.

The Nazis had attempted a show of force. Instead, they had sustained several injuries, lost several flags, had their vehicles smashed, and been chased out of town. This wasn’t exactly new—something similar had happened to them in Wallingford, Connecticut and Peoria, Illinois. But it felt important to us at that moment.

In the United States, after the attacks of September 11, 2001, we were increasingly isolated against the growing chorus of people claiming “now is not the time for militance”—be they reformists claiming that protest was somehow disrespectful or former allies calling for a supposedly strategic withdrawal from the streets. In Barricada, we kept proclaiming that this was no time to stop being combative, and we felt an obligation to lead by example. Our mobilization in York was already our second successful act of mass militance in the post-9/11 times. We had sustained a relatively low number of arrests and injuries. We were starting to believe that “just keep pushing no matter how hard the prevailing headwinds might be” wasn’t just the strategy that most appealed to our youthful enthusiasm and fanaticism, but might also be the correct approach.

That night, we felt great enthusiasm and optimism. Yet writing enthusiastically about anti-fascist victories is difficult today, when a lot of those same fascists and their ideas have now entered the mainstream. It is difficult to reconcile the idea that we acted correctly, both in terms of political analysis and tactics, with a reality in which racist and fascist movements are exponentially stronger than they were twenty years ago. Perhaps we must consider the possibility that we can give our very best, both analytically and tactically, yet still be defeated by historical forces much greater than ourselves. If there is any lesson from history that anarchists should be painfully aware of, it is and that a just idea or cause can be defeated, temporarily or permanently, for a variety of reasons.

I won’t attempt to analyze how racist and nationalist ideas have gained so much traction in the mainstream of society in the US and Europe. Does rainbow capitalism foment an identitarian reactionary backlash? Probably, as a “socially progressive” but economically reactionary society necessarily creates disenfranchised groups who will look for scapegoats and find them in the foreign worker or the darker-skinned neighbor. It is precisely for this reason that revolutionary anti-fascists have always insisted that there is no effective anti-fascist analysis without a critique of capitalism. Should we have focused more on the suit-and-tie fascists, on the racist and totalitarian ideas seeping into the mainstream of society, instead of on the marginal clowns waving swastika flags? I’m tempted to say so, but I suspect that this wouldn’t be fair to the anti-fascist struggles around Europe and the US in those days. It was and is right to confront fascists militantly as a matter of community self-defense. In France in the 1990s, we were already warning against the “lepenization des esprits,” which translates roughly to the “Le Penization of the mind” (Jean-Marie Le Pen being the leader of the far-right French National Front at that time). In the United States, militant anti-fascism has always gone hand in hand with a critique of systemic and institutionalized racism.

The victory in York was significant because it showcased the tremendous potential of spontaneous and organic cooperation between militant anti-fascists from around the region and local Black and Brown youth. Had it not been for them identifying us as allies and trusting us enough to fight beside us, January 12 would have ended in a forgettable standoff. Instead, their initiative and familiarity with the terrain carried the day. Aside from the fact that we had not conducted much outreach ahead of time, the events in York represented a glimpse of what engagement with local communities could look like when we communicated and acted in ways that potential allies could identify with, addressing issues that were relevant to their daily lives.

I’ll let the pages of a 2002 issue of Barricada speak for themselves:

…even more inspiring than the tactical victory of York for the anti-racist movement, are the political ramifications that the action has had. By working on a street level with the local working-class youth, and people of color of all ages, we have made important connections with people who generally fall outside of our demographic. In showing that we can put words into action, that we are willing to put ourselves on the line to stop neo-Nazis from rallying, and that we will use violence to drive them out, we have successfully legitimized ourselves in the eyes of these communities.

In doing so, we have opened the door to further dialogue and cooperation between us. Already, some comrades have discussed having our own anti-racist public meeting in York to help develop these ties. This is exactly what we should be doing now, and any means of facilitating greater connection between ourselves as anti-racists and as revolutionaries and the Black and Latino communities of York should be pursued. Now that we have proven ourselves militant anti-racists, we should seek to expand the debate around racism within York to include an analysis of systemic and institutional forms of racism and propose our own revolutionary anarchist solutions to them. However, the established order is seeking to co-opt our own militant anti-racism with their MTV-style “anti-racism,” which only serves to conceal the real sources of systemic discrimination and racism. We cannot allow our victory to end in a gain for neo-liberalism.

It is heartening to note that it was the working-class youth of York themselves who took the lead in attacking the neo-Nazis, and it was the anti-racist and anarchist activists who followed them, both physically and tactically. By rejecting a leadership role, and acting only as instigators of the street protest, the activists present allowed the situation to become intensely empowering for the locals in the streets, rather than hinder it as has been done at so many large protests in the last two years. While this is attributable only to the people of York, we should seek to replicate this in the future, if possible, by refusing to impose our own tactical decisions upon locals who join us in the streets.

Since the development of the “anti-globalization movement,” there has been a raging debate over why there is not greater participation from working-class communities in either that movement or revolutionary struggles in general in the United States. York, along with the Cincinnati rebellion last year, seem to go a long way in explaining this phenomenon. Clearly, people of color are not reluctant to engage in militant action and risk arrest, as many have claimed in the past, simply because they face higher risk of punishment than white youths. It seems painfully obvious now that when confronted with an issue that directly affects them, as the people of York were when neo-Nazis invaded their city, these communities are often the most militant and passionate about total resistance. In dealing with neo-Nazis, it is not likely that we will need to explain to anyone why they pose a threat to their safety; however, the lesson remains true to all political work we do: if working class people do not directly relate to the issue at hand, then they will not be inspired to fight in large numbers against it.