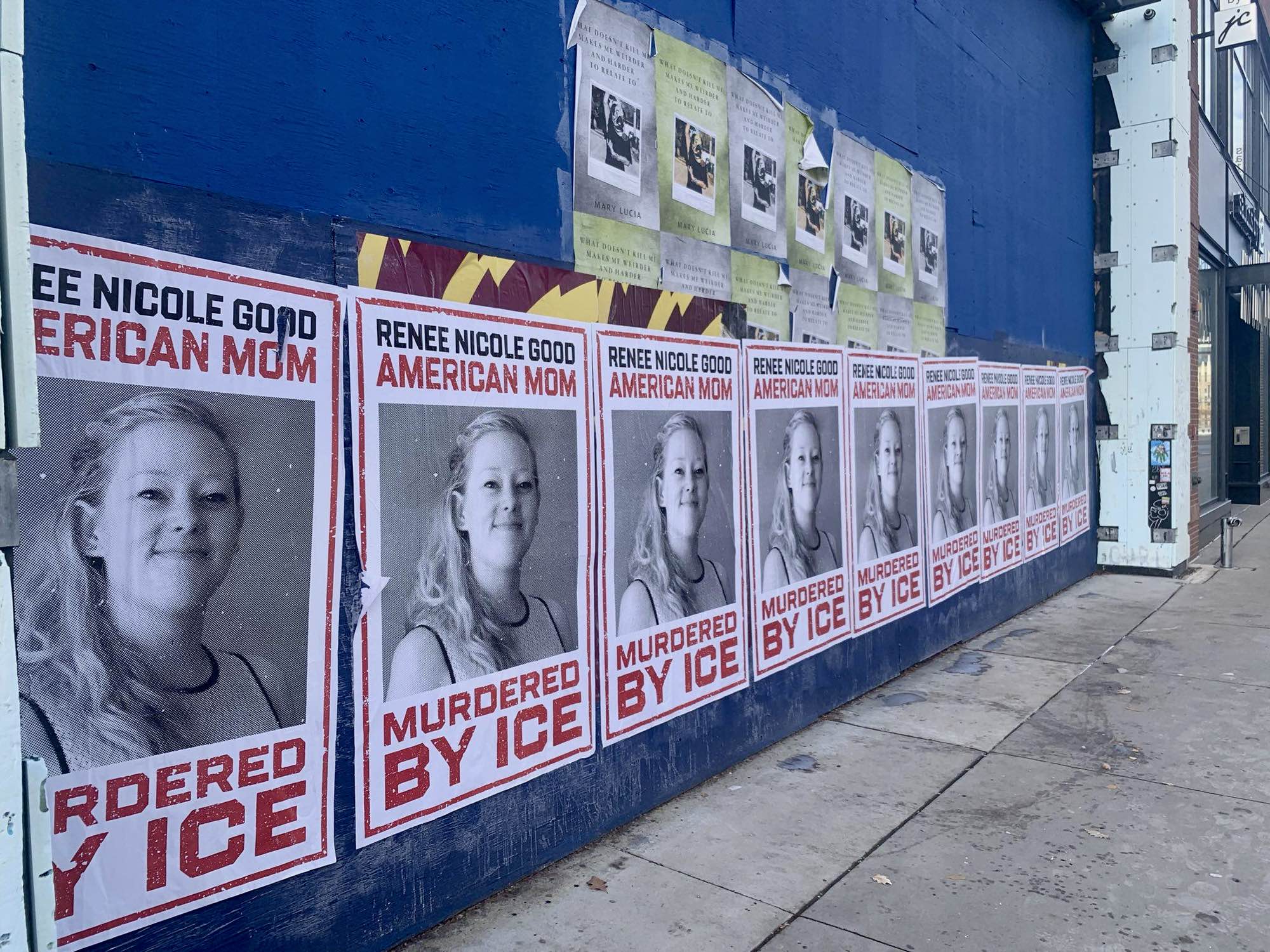

In this report, comrades based on the Syrian border in Turkey describe how they assisted Syrian refugees in escaping to central Europe and tease out the lessons for people engaged in similar work in the United States. Although Syrians themselves led the majority of initiatives to respond to the crisis, people of all backgrounds can play important roles in forming networks of support for the targeted and excluded. As ICE raids intensify around the US, it is time to set up our own emergency response networks and underground railroads.

TL;DR version: begin reading here.

For more on this kind of solidarity work in North America, consult our forthcoming book, No Wall They Can Build.

Legal Disclaimer: This article is speculative fiction addressing the implications of open-border activism.

Syrian refugees trapped against the Turkish border receive water.

“National borders are a bloody stain on the face of the earth. Burn all nations to the ground.” -Charles Johnson

Xenophobia and racism coupled with nationalist and fascist politics are on the rise in the United States and much of the Western world. This puts many different people at extreme risk for a variety of reasons. One time-tested method of survival and resistance is the Underground Railroad—the supported illegal movement of targeted people from harm to relative safety. Decentralized yet coordinated underground railroad movements existed in the American South, Nazi Germany, and East/West Germany at various points in history. However, much has changed since the Second World War including the surveillance and strategic landscapes. We need to be creative and bold to adapt to these changes, utilizing whatever points of leverage we can.

In 2015, we established a project to assist the safe movement of Syrian refugees into fortress Europe. We learned that this work is possible, meaningful, difficult, and complex. This essay serves as a guide to the how and why of what we did, in hopes of contributing to ongoing discourse about this evolving terrain of radical solidarity. We have to stand together and take the necessary risks to counter the waves of violence directed at migrants, refugees, people of color, folks with disabilities, anarchists, antifascists, climate change scientists and activists, reproductive health advocates and doctors, and the broader queer and trans communities. Some 450 US churches have already promised to engage in underground railroad activity under Trump, and groups that have been doing sanctuary and humanitarian aid work on the US-Mexico border for decades are gearing up for unprecedented levels of risk for those attempting to cross. It’s time to build infrastructure and networks for safety and liberation.

How It Began…

Abbey: One night, Quail and I got a call from some of our close friends just down the street in Southeastern, Turkey, north of Aleppo, Syria. They’re a Syrian couple, one a neurosurgeon and one an engineer and participant in Clowns Without Borders—both detained and tortured activists from the Syrian Revolution. They told us that a group of their friends and family were taking a rubber dinghy across the Aegean Sea from Izmir, Turkey to Lesvos, Greece. Our friends were terrified for their safety. I realized that Quail and I had a friend in Athens who could host them. Like many reasonable and decent people in Europe, our friend in Athens was concerned about the refugee crisis. Quail and I reached out to her and asked her if she could host them (about six people) in her apartment in Greece for a night or two as they passed through, just so that they could have a safe place to sleep with wifi and a shower. She did, and they arrived about a week later. She made copious amounts of food for them, helped them navigate the complicated ferry system, got them European Union SIM cards for their phones, and passed along portable phone chargers. Our Syrian friends, although completely exhausted from their journey, ended up getting along well with her.

Quail: It was an inspired connection. The group that stayed with her scattered after Athens. Abbey’s closest friend in the group had the audacity to secure a fake Italian passport and get on a plane from Athens to Germany, where she could declare asylum (!). Another two, newlyweds, continued their journey on foot, passing through Hungary before it shut down its borders completely. I had spent a month in Budapest, the capital of Hungary, over a year prior, researching an article on the reactions of immigrants, activists, and artists to the increasingly racist and xenophobic political climate. Inspired by Abbey’s earlier connection, I recalled that I knew at least a handful of Hungarians and expats in Budapest who would be willing to take the risk to help them. A last-minute ABP to these friends scored them a safe place to sleep for the night in Budapest, a ride further down the trail, and made up one more stop on their ultimately successful journey to Germany. It was an easy favor I had performed for many friends in the past (sure, if you’re going to this random European city, I have a friend I can reach out to if you need a place to crash) but now with much, much higher stakes for all involved.

Both: From this incident, we realized that through Abbey’s connections in Syrian communities and Quail’s connections in Europe we could probably do a lot more than nervously wait for Facebook posts and Whatsapp messages announcing safe arrival to Germany. Quail initially wanted to organize through Couchsurfing.com, where she had the most experience connecting with kind and generous foreign strangers, but the primary platform most Syrians were using on their mobile phones while crossing was Facebook. As soon as we realized how much potential such a group might hold, we launched it. Thus began the Syrian Underground Railroad (SUR), a web-based mutual aid network between US Americans, Europeans, and mostly Syrian refugees.

Refugees arrive at Lesvos in 2015.

The Syrian Revolution, Migration, and Europe

Abbey: Before the Revolution, Syria was an authoritarian police state run by the Assad family, “The Father and the Son,” who gained power in a coup in 1971. Despite some fulfillment of Baathist (multi-ethnic and pan-Arab) socialist policies, such as free college and moderate healthcare, Syrians lived in fear, unable to hold the ruling elites accountable. People felt as though they could not even criticize the Regime to their closest friends without fear that the Mukhabarat (the secret police) and the Shabiha (paramilitary groups in service to the regime) would kidnap, torture, and disappear them and their loved ones. The political system was rife with corruption from top to bottom. Vicious local elites could rule with impunity as long as they were loyal to the Alawite (minority religious group) regime in Damascus, stifling civil society organization or local governance. The many tensions and fractures within Syrian society (ethnic, tribal, religious, and more) were forcibly suppressed through strongman authoritarianism.

In early 2011, while the Arab Spring transpired elsewhere in the Middle East and Northern Africa, a teenage boy sprayed the words “Your turn, Doctor,” on the side of a school in Dara’a—a taunt to ruler Bashar Assad, who was trained as an ophthalmologist. The subsequent jailing and torture of teenagers provoked massive protests, and so began the Syrian Revolution. The regime killed protestors in March in Dara’a, fanning the flames of discontent and encouraging the exponential growth of a wide variety of forms of anti-government resistance.

By 2012, active armed conflict had begun to spread as people pushed to oust the regime. In 2013, a crucial regime ally, Iran, began funneling in aid, weapons, and combat forces through Hezbollah and other paramilitary forces. This initial foreign combat intervention changed the entire nature of the conflict from an internal revolutionary movement to an international proxy war. Later, international presences participated on both regime and opposition sides of the war, with the US, Turkey, and many Western powers siding with the rebels, and Russia, China, and Iran siding with the regime. International geopolitical interventions and neocolonial squabbling (from both “East” and “West”) set a trend of what was to turn a revolutionary movement into one of the largest modern multinational wars. Later, Russia abandoned the charade of proxy support, sending in boots on the ground and extensive weaponry including fighter jets and blasting the cities and countryside. In this way, the nations that eventually set about closing up their borders to refugees contributed to the violence that created the refugee crisis in the first place.

In August 2013, the regime carried out the first of several chemical weapons attacks against protestors and civilians alike as fighting continued to escalate and rebels began making larger territorial gains. Later, the regime continued to use chlorine gas after the UN attempted to dismantle the regime’s chemical weapons arsenal. These are but a few examples of the consistent disregard for civilian lives that became a common occurrence in the war, perpetuated by most sides, but largely attributed to the regime and its allies.

In June 2014, amid massive international infighting for and against the Syrian government and its tactics, ISIS made their first major appearance in Syria and Iraq, capturing large swaths of desert, oil fields, key river territories, and some larger cities. These more experienced fighters, coming fresh out of fighting the US in Iraq under operation Enduring Freedom, joined the fighting in Syria en masse, forming their own factions and taking control of many of the rebel units eventually representing ISIS, Jahbat al-Nusra, and other military factions. This fundamentalist Islamicization was in part a reaction to ongoing Western imperialism throughout the Middle East, which has radicalized, armed, and mobilized fascist elements within Islamic sects.

Throughout this time, a movement for autonomy had continued to take shape in northern Syria in the predominantly Kurdish-controlled areas known formerly as Rojava, now declared the Democratic Federal System of Northern Syria (DFSNS). Their political structure is based on the ideas of American Anarchist Murray Bookchin and Turkish political prisoner Abdullah Öcalan, coupled with their own attempts to practice horizontalism and cooperation across multiple lines of gender, ethnicity, and religion. The Kurdish fighting groups coming from the North were experienced soldiers, especially the former PKK fighters coming from Turkey, owing to a long history of resistance as a result of Kurdish statelessness. However, one of the reasons they were able to sustain themselves in the midst of a massive and multi-pronged war was that they had made an agreement early on with the Assad Regime, receiving autonomy and armaments in exchange for agreeing not to join the anti-Assad resistance. This truce created a sharp divide between them and much of the opposition movements. The United States and other opposition-supporting movements began to hesitantly support Rojava’s fighting units such as the YPJ and YPG due to their effectiveness against ISIS, further complicating matters on the ground about who was supporting who, as Turkey continues to violently oppose Kurdish autonomy.

By 2014 and continuing into 2015, it was no longer so much a revolutionary movement as an all-out civil and proxy war sustained by geopolitical power plays from the international community. The victims were predominantly Syrian civilians; whole cities were leveled. Into 2016, the regime continued to use weapons that violated international war agreements—including chemical weapons, barrel bombs, and phosphorous bombs—and targeting civilians (including hospitals). Throughout more than six years of war, nearly 500,000 people were killed, nearly 5 million refugees fled, and around 6.6 million were internally displaced.

Quail: Millions of Syrian refugees fled to Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan, the countries bordering Syria that still granted visas to Syrians at the time; Turkey currently hosts the greatest number, at two million refugees and growing. Only about one million asylum applications were submitted across all of Europe from Syrian refugees. As is the case the world over, non-citizens displaced from their native country enter into a state of liminal non-personhood which can take years of bureaucracy to resolve; John Oliver did an excellent takedown of UN and state failure to be responsive in allowing refugees to work, go to school, or even qualify as asylum seekers. In Turkey in particular, Syrians faced a language barrier and political resistance to their existence from both the left and the right in the increasingly authoritarian and Islamic yet anti-Arab and anti-Kurd Turkish political environment. In addition, ISIS carried out several high profile bombings and daylight assassinations in our city and its neighbors against Syrian and Kurdish radicals; our friends, the neurosurgeon and the engineer clown, later became targets of these.

The Syrian refugee community in Gaziantep, Turkey was traumatized and disaffected, hardly able to find unofficial work with non-profits in the area that desperately needed their bilingual skills and local knowledge. This labor only intensified their alienation—they were working for the country they missed and could never return to, alongside Western expats earning danger pay (generally triple the Syrian or “local” salaries) who could and did leave for their wealthy native country at the slightest sign of danger and travelled in armored vehicles. When we would hang out with our Syrian friends as they chain-smoked and drank sugared tea, there were two main topics of conversation: Syrian politics, rehashed with the fixation of a traumatized person who cannot escape his tormenter, and their most recent plans for leaving—which embassies they had visited and been turned away from, how their appointments with the UNHCR had been delayed, and, finally, when they had found a smuggler to take them to Greece. All of this was followed by a discussion of the costs, the risks, the fears, and the goal: Germany, the promised land for asylum-seekers.

The USA was out of the question unless they won the UNHCR lottery jackpot (though Trump’s anti-Muslim and anti-immigration rhetoric was as yet a distant threat), and Canada was only possible through official means, which our friends had no reason to trust. Among the wealthier EU countries, the UK was seen as a fortress, France as horribly racist, and Scandinavia as more or less fine—although news traveled fast when Denmark started to make clear that refugees were not welcome there, making it legal to steal from them. Although we had friends end up in all of these places, Germany was perceived to have the best economy, and took measures to improve asylum-seeker quality of life, such as allowing asylum-seekers to obtain legal employment a mere three months after entry. Despite Germany’s culpability in arming and profiting on the war in Syria, the comparatively pro-refugee stance that Angela Merkel, the Chancellor of Germany, maintained at the time, made her a hero in many Syrians’ eyes. In addition, especially later on, Germany was where all of their friends already were. Germany being the most desirable destination, our friends made their arrangements with the cousin of a friend of a friend with a smuggler contact to get on an overloaded dinghy and then employ the free passage granted by Schengen to cross the internal borders of the EU to their destination.

It was a race against the clock, as the constant flow of refugees had begun to crack the infrastructure of European immigration, setting the stage for xenophobic political parties to seize power. Our Syrian friends feared that the internal borders of the EU would close. In the end, they were right.

Residents wait in line to receive food aid in the Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus.

Why We Were There

Abbey: I’d been following the Syrian Revolution from the beginning as a result of my interest in the Arab Spring and revolutionary political movements in general. This eventually led to me making connections and obtaining an invitation from a Syrian organization with which I worked for the following eight months. In the beginning, I had no idea how much worse the war would get. I wanted to help without intruding, but I also just wanted to understand.

Aside from my sense of horror and powerlessness, I also felt particularly drawn to the Syrian context due to the numerous parallels I saw between it and the fractious nature of US politics. Of course, so much of the violence in Syria, even before the war, is beyond what most Americans can comprehend. I shudder now when people call the US a police state—I know from stories how much worse it can get. But aside from this, there were certain similar contexts in Syria and the US: religious tensions, urban/rural divides, lurking racial and ethnic injustice, repression (albeit significantly less in the US), and burgeoning resistance movements regularly flaring up in spite of violent reprisals.

Before I left, I also developed a strong interest in the revolutionary democratic movement in what was then referred to as Rojava. It was not until I had built complex relationships with Kurdish radicals from the region that my conception of the Bookchin-inspired multiethnic anarchist movement fighting ISIS became complicated with the ethical realities of war and power. The part of me that had considered heading to Kobanê (where I was invited to a later cancelled wedding), Efrîn, or Qamişlo to support and witness was overcome by the reality of how resource-intensive it was to get foreigners in, how dangerous it actually was, and how mixed my Kurdish friends’ feelings were about the movement and me going. Further, whatever dark part of me wanted to be a war tourist was squashed by my debilitating empathic response to extreme violence.

Quail: Abbey and I worked alongside our Syrian friends from the summer of 2015 to early 2016 in various non-governmental organizations. We both had Masters degrees in Peacebuilding and had been working from the US but in international contexts. We knew that our role as white outsiders was fraught—on the macro level with colonialism, imperialism, and general US domination, and on the micro level with the privilege of our nationalities and statuses, native language, and education.

In hopes of being more a part of the solution than the problem, we followed a rough ethical outline: we only took on work we were invited to join in (thus, they consented to our presence), we only worked for Syrian NGOs (decreasing the income disparities between us and our Syrian friends), and we sought to support these Syrian-led initiatives by leveraging the privileges we had. I could write in proposal-speak English, so found myself as the Grants Coordinator at a Kurdish humanitarian aid organization, representing the work to other English-speaking donors. Abbey had exposure to data work so she could run reports for Syrian grassroots programming while training the staff there to do the same in the future. We did our best.

Our Motives for Running the Syrian Underground Railroad

Quail: First and foremost, we were trying to support our friends and their friends and families. I know for me, part of my motivation was to do something, anything, in the face of the refugee crisis, particularly in Greece, where thousands were dying crossing an international border I could easily cross via boat or plane with my US passport. These were senseless deaths of people already fleeing mortal violence. The injustice was palpable.

The political energy surrounding the crossing of the refugees was crackling: hundreds of thousands people beating the odds against them—women crossing while pregnant, whole extended families, the urban poor, farmers, and people from the middle class who had never slept outside before. I couldn’t help but cheer on such brazenness. The media and Facebook groups that popped up around the crisis were full of shocking and, yes, compelling stories about people dodging customs officers and ducking fences, being forced at gunpoint to pay double at the last minute by smugglers, dressing up as wedding parties, getting out of boats and pushing when the gas ran out, babies born on the beach upon arrival. It was the unfamiliar that I’d been privileged not to know (namely, war—at least, I hadn’t been on the receiving end), brought to the same beaches where I’d spent a sunny spring break in high school. I think it was this juxtaposition that grounded my desire to counterbalance the privilege I knew myself to have and to support those willing to take on such an impossible journey for the sake of their children. It wasn’t until well into the work that I learned there were words for this: mutual aid and open borders.

Abbey: I am invested in open borders as the result of diligent research into the ethics, economics, and net human benefit that they create (see Appendix below). I saw the Syrian crisis and the plights of my friends and their communities as a chance to put those values into practice.

Syrian refugees march along the highway towards the Greek border in 2015.

The Network

Abbey: It was some time into working in the region that we founded the Syrian Underground Railroad. We created it as a secret Facebook group, so a person could only get added by someone who knew them; that way, it wasn’t otherwise searchable. This was our attempt to ensure that only people with at least one person who could vouch for them entered the space. Because of this limiting factor, we knew that the group would have less far-reaching impact than other resources—there were other groups with thousands of members—but also less chance of drawing the attention of racist trolls or law enforcement.

Then we added every European and Syrian friend we could think of who would be interested and encouraged them to add others that they trusted. Overnight, there were over 200 people and it kept growing every day. We encouraged the Syrian members in transit to post about what they needed and for the European members to offer what they could. We set the group’s core values as mutual aid, solidarity, respect, and kindness. It wasn’t long before requests for various things started pouring in. The process immediately became overwhelmingly disorganized.

Quail: It was both a blessing and a curse that we were able to launch something immediately. We made connections of potential mutual aid, but we had to navigate several hundred people on a fixed platform. The legal concerns were real. We felt exposed running the group on Facebook accounts. We tried consulting with a friend of mine involved with immigration law; given the dozens of countries involved, she didn’t know where to start in advising us, though she was enthusiastically in favor of the work we were doing. Ultimately, we ended up setting up the best stop-gap we could against the kind of illegal activity we believed would be most dangerous. This was an admin statement reading:

“The admins of this page cannot offer anything that involves the exchange of money and additionally do not support paid “fixers,” smugglers, and the like. Any paid services such as these will be deleted or blocked for security reasons. This page is a free mutual aid support network. The admins of this page cannot support or condone any illegal activities, nor can we take responsibility for potentially dangerous decisions members of the group might take. We do, however, believe supporting refugees in the way we are will prove to be on the right side of history.”

We hoped that this would be sufficient.

Abbey: We brainstormed ways to keep things as user-friendly as possible for ourselves and for those seeking aid. I compiled a spreadsheet of those offering help: their contact information, where they lived, and what they were willing to offer. Once we had this, it was easier to refer or tag people as necessary. From the list of those willing to help emerged a core group of three people who had extraordinary willingness and capabilities and were especially responsive to requests. We made them into admins on the page. One was a tech whiz living in Germany, one was an asylum expert in Europe, and one was a bilingual Syrian mother still in Aleppo. She ended up enthusiastically translating all our English materials into Arabic and helping with other things as needed—amazing, considering the fragility of her own situation. This enabled our Syrian friends to post in Arabic if it was more comfortable for them.

Additional concerns included security and accessibility. We set up the initial video meetings through somewhat secure mediums such as Jitsi, at which we discussed our short- and long-term goals, security, and capabilities. We then created a riseup.net email account to handle whatever secure email dealings we needed, though it was little used—quite a bit more happened over Facebook messenger, despite the security risks. This was just because so many Syrians are fluent in Facebook, while other tools are not always accessible. At that time, Whatsapp did not even have the Whisper Systems end-to-end encryption yet, which would’ve been ideal as Whatsapp was the texting medium of choice for our Syrian friends. We also used Signal or Telegram (secret chats) for international texting where possible, teaching members of the group to use them for messages that might be illegal or cast undue suspicion.

Quail: Since most migrating refugees were operating entirely on Facebook, I solicited, researched, and compiled all of the relevant Facebook-based resources for making the journey, organized by location (which Greek island, which country), affinity (anarchist groups, apolitical groups), and purpose (to organize and inform volunteers, to update everyone about specific needs and situations). Alongside this resource page, I kept a list of reputable places asking for volunteers and donations, for our friends and family who wanted to help. Before we knew it, the group had over 500 members, with multiple posts a day and several responses to each post. Although at the beginning we were scrambling to plug every leak in the systems as we developed them, what we were doing was starting to work. We also began to connect with other autonomous groups doing similar things, and to exchange resources and services.

Refugees break through the border between Syria and Turkey.

Results: The Work Itself

Both: Through endless posting, messaging, contacting, and networking, though limited by our desire to remain on the legal(er) side of a chaotic situation and by our means, time, and contacts, we directly supported dozens of Syrians in achieving their goals of migration and asylum. We recognize that in the face of a multi-million-person refugee crisis, this accounts for very little—we were one tiny facet of a truly remarkable spontaneously emerging network of thousands of initiatives that responded to the crisis in the best ways they could. There were many other groups like us. With that sense of scale in mind, here is what we achieved:

-

Facilitated the money transfer that got a wounded civilian out of Yarmouk (a Palestinian refugee camp in Syria) and into Lebanon for emergency medical care

Abbey: I was able to link someone in the US who had access to money and a preference for direct transfers to a friend who was connected with the wounded man in Yarmouk. Because of numerous legal restrictions in moving money to the Middle East and the corruption in Syrian money transfer services, the money was sent to me first. Then I passed it on to a friend who had a bank account in Damascus that he could deposit into from abroad. In Damascus, someone withdrew the money and gave it to the person, who was almost immediately able to leave. He could certainly have died without the care.

-

Helped one member to reunite with his wife in France, connecting him with contacts in the local mayor’s office to facilitate his asylum process

Quail: A coworker’s wife had found asylum in a small town in France. The friend was trying to gain asylum legally, but needed some political heft to succeed. Abbey reached out to a French anarchist group, part of the International Anarchist Federation; within a few days, she had secured the phone numbers and emails of the people he needed to speak with. He and I unsuccessfully tried to Skype in with these people for several days, until he decided to take the situation into his own hands and get on a boat. Once he arrived on a small Greek island, he messaged us for help; Abbey was able to get him an Airbnb with an apparently pro-refugee host (as hosting undocumented refugees is illegal and punishable by jail time), gaining him a night of good sleep and a shower before his long journey to France. When he eventually arrived in France, he was able to use the contacts we had procured to push forward his difficult asylum process.

-

Helped dozens of people find housing, a shower, internet, phone access, water, and food along their travels from Syria to Europe

Abbey: The numbers for this are difficult because we were more concerned with doing these things than documenting them, but also because we don’t actually know the full extent of how many connections occurred through the group off the main feeds. Lots of people told us how essential these little “comforts” could be. A shower could help one appear less like a haggard traveller, making one less suspicious to prowling police or anti-immigrant groups. A short wifi connection allows a person to tell her family that she survived the boats. Food and water are heavy and expensive, and Halal is difficult to find in prepared food restaurants. A home-cooked meal does wonders for nutrition and morale.

-

Provided emotional support to countless people struggling with the many dilemmas of migration

Quail: Many times, admittedly, we were powerless. A Syrian refugee posted from a literally miles-long queue outside of a refugee camp in Germany in a panic: he was being rained on, he was very hungry, and he was afraid that he wouldn’t make it inside by nightfall. I tagged our German contacts on the post, but it was already late evening. A few others tagged their own friends. If nothing else, people offered their empathy—“That sounds so terrible, I’m so sorry.” Eventually, he made it inside (snuck in, if I remember correctly), from which he reported triumphantly and gratefully for all of the support we had offered. Such support yielded nothing tangible, yet it had heartened him. That counts for something.

Abbey: We spent many long nights just helping people sort through all of their complex considerations, dilemmas, fears, and hopes. But when there was nothing fruitful to be said, even just listening was warmly welcomed. I remember receiving frantic Whatsapp messages from a friend who was trying to get through the closed Macedonian border and was stuck in the pouring rain without food along with thousands more people, many of whom were injured, pregnant, sick, elderly, or young, with no idea where they could go. He called us, panicking, as heavily militarized soldiers began herding them to unknown destinations. He feared that they were being led to the slaughter. In situations like this, often the best we could do was to call the Red Cross, border patrol agencies, and other local NGOs to try to get a sense of the situation and alert anyone who could possibly help. Many times, this was fruitless: everyone, at every step, seemed overwhelmed, and either numb or hostile to the plight of the lost refugees. However, we were able to confirm that the location they were being led to was a different migration route, and inform our friend so that he could then inform others in the crowd in Arabic—many times, groups of soldiers would not even have translators, only guns and dogs. Throughout these tense moments, even in our helplessness, many people reported how much better they felt just to know that someone, somewhere, knew where they were and what was going on—and cared.

Ultimately, we aided migration out of Syria into Europe in over 40 known instances.

Escaping across the Hungarian border.

Ethical Complexity

Quail: There was great potential for us and our more privileged friends to tokenize, fetishize, and in other ways express racism, xenophobia, and white savior mentality in our relations with our Syrian colleagues. Wherever possible, our network attempted to cultivate a spirit of solidarity, not charity. We tried to be vigilant about the risks at play in our dynamics, though we didn’t let that fear paralyze us. We ultimately had to trust ourselves to do our best and be accountable. From staying in touch with many of the people who accessed our services, it seemed that the bulk of relationships between hosts and refugees were substantive and respectful. Many remain friends to this day.

Abbey: One critique leveled against an organization that was doing similar work was that, in aiding migration, they were encouraging people to run the risks associated with the journey. This critique could certainly have been leveled at us; it’s something we thought about a lot. It implies that refugees are somehow incapable of making decisions for themselves, which is condescending. However, our perspective on the risks did change in the course of the work. In the beginning, we had a more hopeful outlook on the migration process, because in general, the risks and costs were lower and people were frequently succeeding. In addition, we felt that if people were already deciding to migrate, they deserved to be supported in minimizing their own risks. It is possible that our trust in the process influenced people, but fortunately none of the people we spoke with were harmed beyond receiving physical abuse from border police—which, terrible as it was, wasn’t comparable to drowning in the Aegean. As time went on and the situation became more and more devastating, however, we began to grow pessimistic about the risks of entering Europe and began trying to focus on asylum processes wherever possible. Quail’s desire to do this work beyond the computer led her to volunteer on Lesvos. On that island, she witnessed some of the atrocities that became common. As we grew bitter about the process, we began to discourage people more, though still ultimately supporting their decisions regardless. Throughout these shifts in perspective, our goal was simply to provide people with the most accurate information we could and to support their decisions.

Quail: Information-sharing networks connecting settled refugees and fleeing refugees were fully operational at every juncture of the refugees’ journey, mostly in the form of extended networks of family and friends communicating updates via Whatsapp. Such networks were more likely to avoid the pitfalls we navigated as white US citizens. But the downside of Syrian-only support networks was that, without many linguistic and cultural translators able to access the contexts in which they were traveling, rumors calcified into fact, fueling and misdirecting the travelers’ already overwhelming hyper-vigilance. Smugglers trying to make a sale, friends and media exaggerating, the refugees’ own idealism and desperation—all these came together to craft a distorted picture of the journey. We tried to keep updated resources on all the different situations along the various paths. While I was in Lesvos, I connected an Arabic-speaking volunteer to a radical Syrian press to address some of the rumors and misconceptions, mostly in hopes of spreading information about how dangerous the journey was. Internews also started a RUMOURS project in Arabic, Farsi, English, and Greek, addressing some of the most recent rumors that had been repeated by arriving refugees. A member posted these regularly on the Facebook group. This interchange between Europeans, Syrians, and other refugees was vital to confirming the validity of information passing through migrant networks.

Both: Probably the biggest ethical issues happened in situations where we didn’t have access to any means of helping people in extreme need or we were just so traumatized and exhausted that we couldn’t do it anymore. Those were the most heartbreaking moments. It became clear in those moments how many volunteers were frantically scrambling, just like us, yet unable to meet all the needs. We did our best, building networks of trust where duties could be distributed according to ability and capacity to ensure sustainability. But this was an international crisis and we were only a handful individuals, connected and resourceful though we were. Our offers of help may not always have lined up with our capabilities. We were not the UNHCR, the IRC, or any sort of official group with a budget and influence, although volunteer-driven groups consistently proved more responsive, principled, and effective. To paraphrase the working definition of disaster used by emergency professionals—disasters fundamentally overwhelm a community’s ability to take care of itself. If every need could be addressed, a situation would not be a disaster. The so-called migrant crisis was a man-made disaster—and we could not begin to meet every need, let alone address the causes.

Alternative Strategies

Both: The will to support targeted people through less-than-legal means can take many forms beyond a web-based mutual aid network. Here are some of our favorite examples from throughout history, organized both by those affected and by people acting in solidarity. Hopefully, they can provide you with further inspiration as you determine the best form for your resistance to take.

Lesvos—Starfish Camp

As mentioned throughout this essay, Quail spent several weeks on Lesvos Island in the Aegean Sea, one of the major boat arrival points for Syrians and other refugees. There, she worked with the Starfish Foundation to help welcome refugees arriving by boat and transport them to the other side of the island so they could move on to Athens. There are many more volunteer reflections of the experience, as the untrained 20-somethings who had the free time and the gumption to join in the work confronted the harsh realities of a humanitarian disaster. The spontaneous emergence of local-led volunteer initiatives offered hope, even as they included their share of frustrations and shortfalls. We ushered refugees off their boats, got them to a transit camp pitched on the parking lot of a nightclub where there was water, gave each of them a sandwich and, hopefully, shelter, and coordinated bussing thousands of them daily to the next camp, where they could be registered so as to legally take a ferry to their next destination. Starfish, like the other organizations on the island, was semi-official, working in conjunction with the UNHCR and the Greek government. However, our work was only legal because the law had yet to catch up to the crisis. Once it did, Spanish lifeguards and other volunteers were arrested and refugees were imprisoned while awaiting asylum processing—where they remain to this day, withstanding regular riots and a large-scale fire.

Border Caravans

Border caravans are a time-honored method of moving people through militarized border areas in a protective cluster of transportation vehicles. The basic tactic is to gather a large group of documented people with undocumented people protectively interspersed throughout and then rush a border, crossing all at once so as to overwhelm any sort of border protection in order that the undocumented people cannot be captured. The route many refugees took in their trip towards central Europe constituted a sort of caravan; thanks to sheer numbers, refugees were able to overwhelm border control agents, especially those with unclear orders. Solidarity caravans also took place throughout the crisis, including in the Balkans and Germany. There are also many variants to border caravans. The School of the Americas Watch Convergence which took place in Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora (Mexico) culminated in a checkpoint shutdown. Two hundred people obstructed the functioning of the checkpoint, facilitating the free passage of the hundreds of cars that passed along I-19 that day traveling North. This border checkpoint has the blood of countless dead on its hands, as many migrants die in the surrounding desert trying to circumvent it. Another creative and funny example was the group that dressed up as a wedding party to push through checkpoints with migrants hidden amid them.

Anarchist Squats

As thousands of refugees arrived on the shores of Greek islands, many began to realize that the most difficult period of travel was still ahead of them. The difficulties were myriad, ranging from logistical (Where am I going to sleep tonight if it’s illegal for me to stay in a hotel and the transit camp is about a thousand people past its 200-person capacity?) to cultural (What language is being spoken here? Is this food halal? Is that person glaring at me because I’m wearing a hijab?). Many anarchists stepped up to address these difficulties, organizing heartwarming pro-refugee rallies. Anarchists opened several squats, notably in Greece, to house migrants passing through. In Tucson, Arizona, several communally-organized homes serve as landing spots for migrants who have been recently released from Border Patrol/ICE custody. Providing regular housing to migrants is not without risk: one squat in Athens withstood a serious arson attempt. Fortunately, no one was hurt.

The Great Dismal Swamp

Going back in history, in the Great Dismal Swamp spanning Virginia and North Carolina, “maroons,” or fugitive slaves, maintained horizontal communities in locations so inaccessible that they could live free. These stories are often erased in the whitewashed history of slavery resistance that focuses on white abolitionists and minimizes black-led resistance efforts throughout the US. Yet as early as the early 1700s, communities of runaway slaves, Native Americans, and escaped white indentured servants were raiding nearby swamps for food and livestock, and establishing more or less permanent settlements that lasted until the US Civil War. Today, we might consider establishing similar communities based in mutual aid and mutual protection, although much has changed since slavery when it comes to living off the grid.

German “Escape Agents”

Among the many amazing tales of people escaping from East to West Germany during the Berlin Wall era are the stories of the escape agents. Sometimes professionals and sometimes concerned citizens, escape agents would facilitate the passage to freedom, outfitting cars and trucks to smuggle people, assembling small aircraft, and falsifying passports. Although the erection of the Berlin Wall deterred a great deal of migration, it never fully prevented it. This history lesson should be useful under the new US regime: walls can staunch but never completely block the free movement of human beings. Human ingenuity is boundless, particularly when people confront seemingly impossible situations. The German organizing site fluchthelfer.in linked the work going on during the Syrian refugee crisis to this heritage that their country now is proud of, in spite of the fact that it was illegal at the time. They set up underground networks of transportation systems for refugees and trained people on how to do the work.

Tohono O’odham Reservation and Indigenous Border Resistance

As long as there have been imperial nation-state borders, there has been indigenous resistance. National borders are inherently colonial, and they often cut through traditional tribal territories. The Tohono O’odham tribal reservation in Arizona (and Sonora) was divided by the violent acquisition of what had been Mexico and the creation of the contemporary US/Mexico border. Not long ago, in 1994, migration between Mexico and the US was shut down amid fears of mass migrations as a result of NAFTA. Resistance to the borders continues to this day. Members of the O’ohdam tribe continue a long tradition of providing hospitality towards migrants crossing into their lands, including simply providing aid from their back porches. Despite some pro-Border Patrol and anti-immigrant political stances from reservation government, much of the O’ohdam leadership has stood by their longstanding resistance to border militarization and declared that a wall will never be built on the 75 miles of the border that they control. The tribal Vice Chairman has stated that Trump’s wall will be built over his dead body. This stand mirrors other Indigenous, Chicanx, and undocumented resistance to colonialism (see Appendix).

No Más Muertes

No Más Muertes/No More Deaths is a solidarity humanitarian aid organization that came out of the sanctuary movement of the 1980s in Southern Arizona. It runs an aid camp south of the internal Customs and Border Patrol checkpoints that litter the roads up to 100 miles north of the border, providing food and shelter to migrants forced to cross the deadly Sonoran desert. It also maintains a network of water and food caches along the various migrant trails in the area, supports shelters south of the border for migrants and deportees, documents abuses that the Border Patrol perpetrates against migrants and aid workers, and supports a legal clinic for undocumented people in Tucson. The work involves legal challenges of its own; in 2005, two volunteers transporting undocumented patients to a hospital received a felony charge of aiding and abetting, which was ultimately dropped thanks to community organizing around the campaign “Humanitarian Aid is Never a Crime.” No More Deaths volunteers remain on the frontlines of a highly politicized border struggle, especially now that Trump is moving forward with his plans to build a wall.

Residents hang their clothes to dry in a squat opened in Athens by anarchists to provide housing for migrants.

Relevance to the Situation in the United States

Abbey: The Syrian refugee crisis across Europe and the Middle East is not unique in the global landscape. The US Southwest has a parallel situation, with folks crossing into the United States predominantly from Mexico and Central America. As xenophobic, Islamophobic, racist, and sexist sentiments and legislation proliferate, we may need to resurrect the underground railroad as a means of resistance and supporting targeted persons—whether that means escaping into, within, or from the United States.

For undocumented persons in the United States, an underground railroad might look like decentralized networks of safe houses, aid, or transportation including emergency response networks. For activists and antifascists, there will likely be a need not only for safe houses and go-bags/bugout-bags (tailored to the needs and threat model of the individuals), but also for paths out of the United States, such as to Mexico or a non-extradition country. Anyone who might be targeted by the state (or other organizations that act in tandem with and sometimes more overtly than the state) should have a plan figured out ahead of time. To arrange a safe house, think of a friend that you trust but are not regularly connecting with over Facebook, email, or any regular contact that could be monitored—someone you can trust, but that your pursuers would never think to investigate.

In Syria and Europe, with a million refugees in transit, our group of less than 500 people was such a small drop in the bucket that even through a medium as intensely monitored as Facebook, we seem to have been able to fly under the radar. In the United States right now, you should assume that anything you type or like on any social media or unencrypted media is being handed directly to government surveillance programs and being monitored according to the interests of the current regime. The risk in the US is much higher, even for smaller groups. However, you can still accomplish some things on Facebook if need be. Just take precautions: keep things on a smaller scale, employ coded language (arranged offline), and use secret groups to increase the likelihood of group member accountability. For conversations over Facebook, the end-to-end Whisper Systems encryption function of Facebook messenger is live, although it remains imperfect, as Facebook still collects and uses metadata from those encrypted conversations, unlike Signal.

If we are to employ underground railroads in the current US surveillance landscape, these efforts ought to be decentralized, based in affinity groups, cells, neighborhoods, and horizontal networks. Without leaders, our movements present no easy targets, so it won’t disable us if one person is caught. The fewer figureheads, the less hierarchical bureaucracy, the more stigmergic, adaptive, efficient, and complex our organizing can be. Complexity can be our saving grace in a political climate of great pressure. We need to be creative, careful, and flexible in choosing platforms and organizational models. The forthcoming crackdowns in the United States will be intense, but if we build networks of trust, plan ahead, and practice strong security culture by using accessible anti-surveillance tools, we can make this work sustainable.

Conclusion

Abbey: This work was not just a responsibility—it was also a sheer delight. By and large, refugees are just people fleeing extreme difficulty, genuinely grateful for whatever support was offered without pretense or condescension. I can’t tell you how many times Syrian refugees made me dinner or offered to have me stay in their houses. Syrian culture emphasizes hospitality, and that lent itself naturally to mutual aid and deep friendships. Solidarity, even across boundaries of power and privilege, can be a form of mutual aid in that the benefit is mutual. Our liberation is interdependent. We cannot be free or get free without each other. I have Syrian friends who I count on to be there for me. We didn’t earn each others’ trust with empty words or rhetoric about “allyship.” We earned mutual trust through actions. I earned theirs by being an accomplice.

Both: To create a network like SUR, all it took were a few people with connections on both sides of the border, in multiple communities in the target area, who could cross the divides between cultures. Those of us positioned in wealthy Western nations have a responsibility to those exploited by our military, government, and corporations. Solidarity just requires the explicit consent and interest of those involved, the willingness to run a certain amount of risk, and the intellectual and emotional diligence to resist casting oneself in the role of savior. It can start small, even stay small, and the impact can still be meaningful. Build or join a community that redistributes power and access to resources. There are myriad ways that we can make Trump’s America safer for those at risk.

Alternatively, if you’re reading this as a migrant, keep that hustle game strong. We’ll try to have your back.

Tear down the walls.

Appendix: Further Reading

Open Borders and Migration

- A No Borders Manifesto

- Assessing Immigration Policy as if Immigrants Were People Too

- Border Patrol Nation

- Clandestine Migration

- Hired Farmworkers: Background

- Increased Immigration Is Unlikely to Increase the Size of the Welfare State

- Is There a Right to Immigrate?

- Relying on Rising Immigration to Achieve Budget Surplus

- The US Already Spends Billions on Border Security

- US Spends More on Immigration Enforcement than on FBI, DEA, Secret Service, & All Other Federal Criminal Law Enforcement Agencies Combined

Chicanx Resistance

- Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza by Gloria E. Anzaldúa

- Brown-Eyed Children of the Sun: Lessons from the Chicano Movement, 1965-1975 by George Mariscal

- Chicano! History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement

Printable PDF Version of This Text