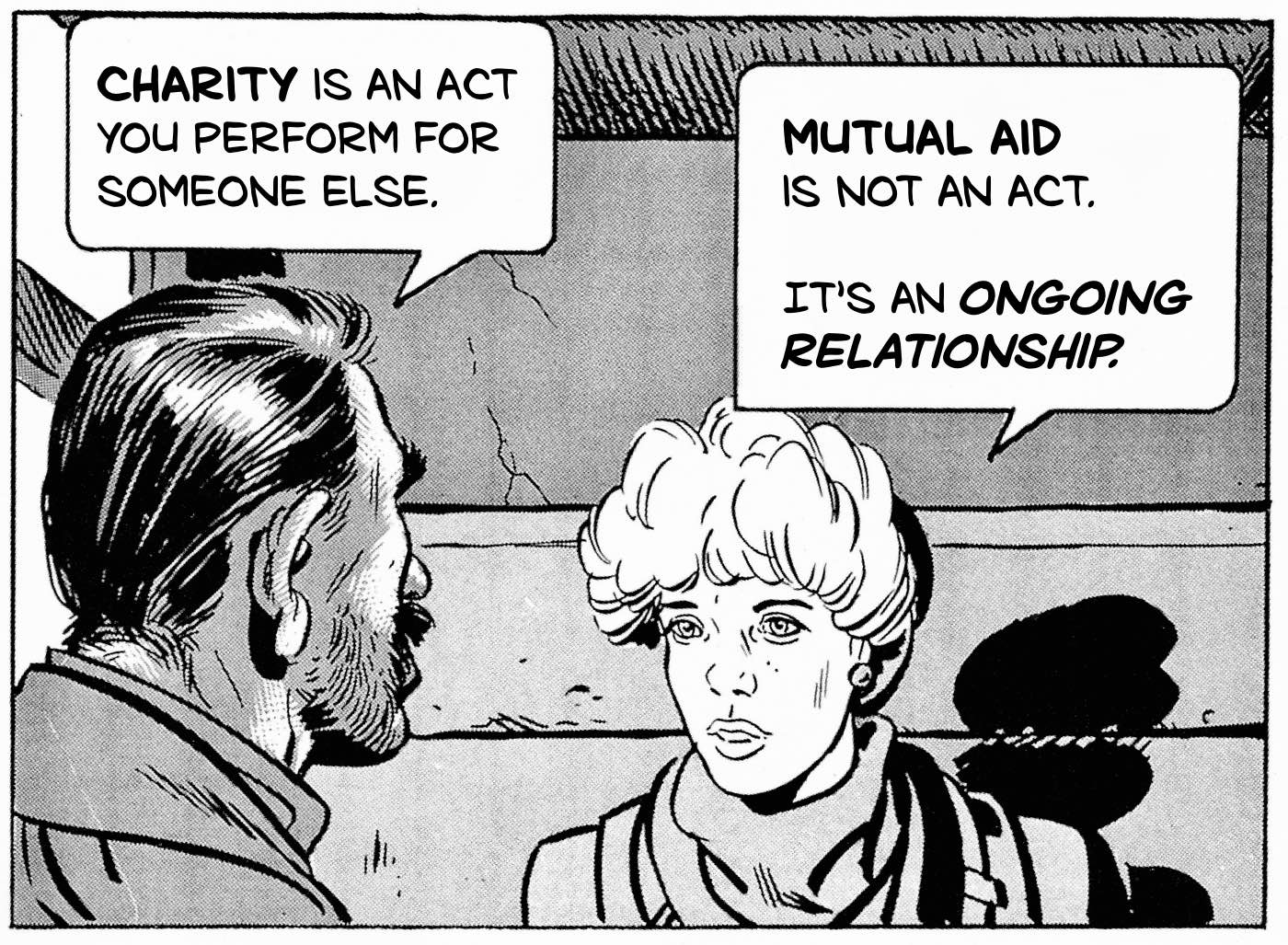

Much has been made of the distinction between charity and mutual aid. Charity is top-down and unidirectional, while mutual aid is supposed to be horizontal, reciprocal, and participatory. In practice, however, the majority of today’s self-described mutual aid projects remain more or less unidirectional efforts to provide goods and services to those in need.

This has contributed to a situation in which conventional non-profit organizations are rebranding themselves with the language of “mutual aid,” while some anarchists have given up on the concept entirely, fed up with a rhetoric that some say amounts to “mutual aid being good and radical, and charity being bad and conservative.”

Is there more to the distinction than this? How could we unlock the revolutionary potential of mutual aid?

Is It Mutual Enough?

Is the difference between charity and mutual aid simply that mutual aid involves reciprocity? There are a few problems with this proposition.

First—in a world in which resources are distributed so unevenly, is mutual aid only possible between those who have similar access to time or resources, so that they are capable of reciprocating? Is mutual aid just barter in disguise? Are those who benefit from mutual aid indebted? How should we determine whether our aid is reciprocal enough?

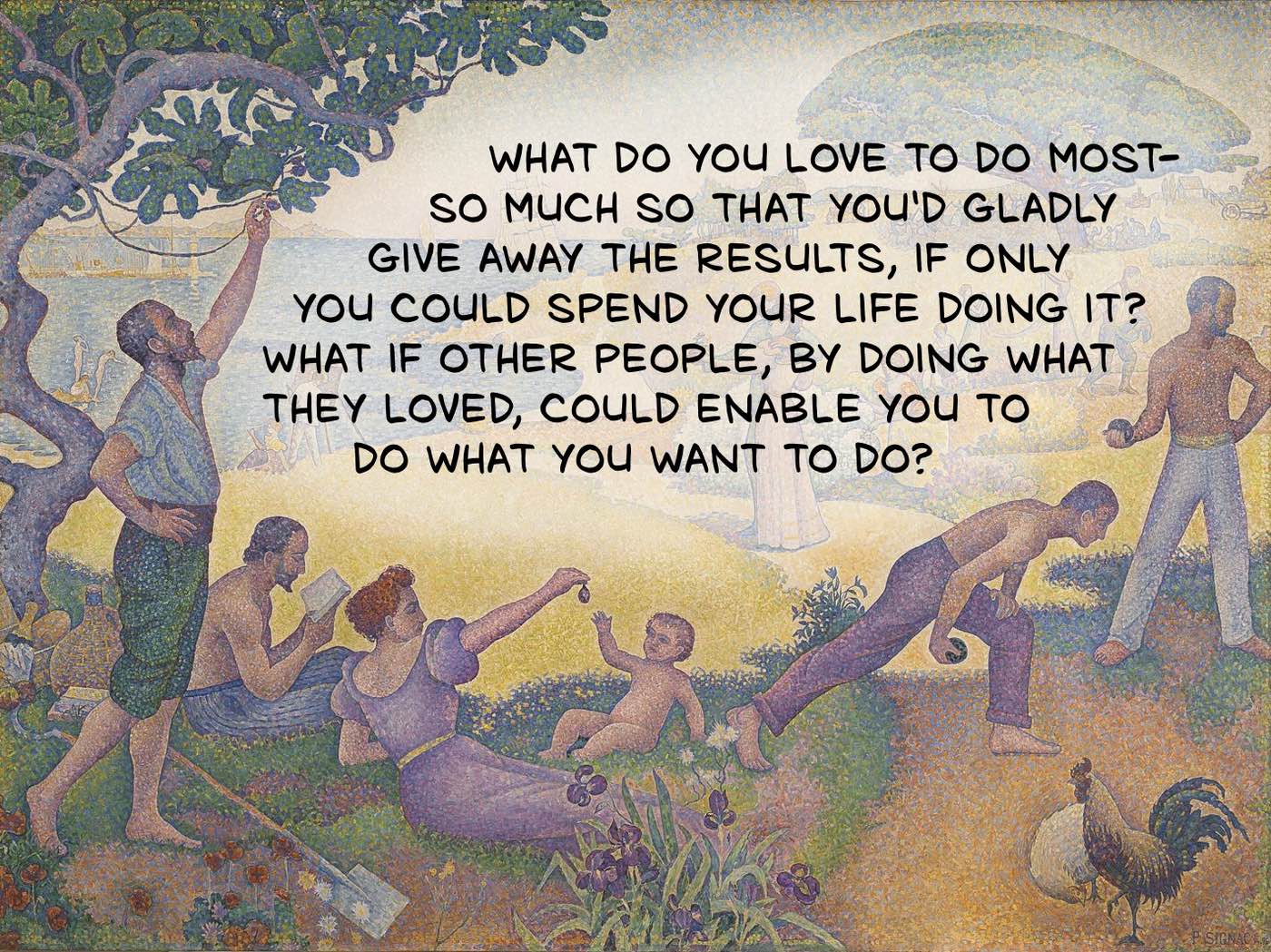

A senior citizen who has dedicated her life to caring for her community should be able to leave Food Not Bombs with a bag of bagels without anyone accusing the organizers of engaging in mere charity. Likewise, it should be possible to receive treatment from volunteers with medical expertise even if you cannot provide comparable treatment in return. The idea of mutual aid is not to establish a market in which people trade volunteer services, but to create a commons in which all of the participants can meet their needs without keeping score. In the long run, the goal is to bring about a situation in which everyone is at liberty to do what they most wish to do and can share the fruits of their activities with everybody else without need of compensation. This is what we call a gift economy.

When people get to do what they love most, rather than being forced to squander their lives on tasks that they do not care about, it takes a lot less to feel prosperous. By contrast, those who seek to profit at others’ expense find that no amount of material wealth is enough to satisfy them.

Exchange economics frames life as a contest between bargainers who maneuver to outwit each other in order to control pieces of a fragmented world. Free trade, the free market—these are oxymorons: where profiteering can bend everyone and everything to its prerogatives, eventually no one is free to focus on anything else. Exchange economics imposes a one-dimensional scale of value, according to which everything can be appraised and traded. Today, this framework has taken over all of our relations and means of survival. This is why so many people are materially, socially, and emotionally impoverished.

The gift economy prevails wherever people can share things freely without keeping score. In gift economics, the participants receive more the more they bestow—not only because generosity tends to beget more of the same, but also because gift-giving is its own reward. Everyone who has shared a real friendship or attended a successful potluck has seen that when the opportunity presents itself, human beings enthusiastically return to this way of relating.

What is “mutual” in this context is not reciprocity, per se, but rather that the activities enable people to give and receive freely, fostering relations without measure.

If that is indeed our goal, however, it sets a much higher bar than mere reciprocity. To get there, we will have to do more than redistribute resources. We will have to foster a widespread sense of agency and initiative and faith in the value of sharing—and ultimately regain collective control over parts of our lives and our world that capitalism has taken from us. This provides better criteria for evaluating the success of mutual aid efforts than simply how many goods changed hands.

Beyond Individualism

At its worst, today’s mutual aid is a Signal loop in which strangers post individual requests for money, one after another, in hopes of receiving anonymous donations. Poor people are often more generous in proportion to their means than the wealthy—but if mutual aid simply means passing the same weathered five-dollar bill around in a circle, it probably will not suffice to solve our problems. Likewise, if mutual aid only collects resources that go directly into the pockets of landlords and debt collectors without doing anything to advance the struggle against their power, it might help us survive in this society, but it will not help us change it.

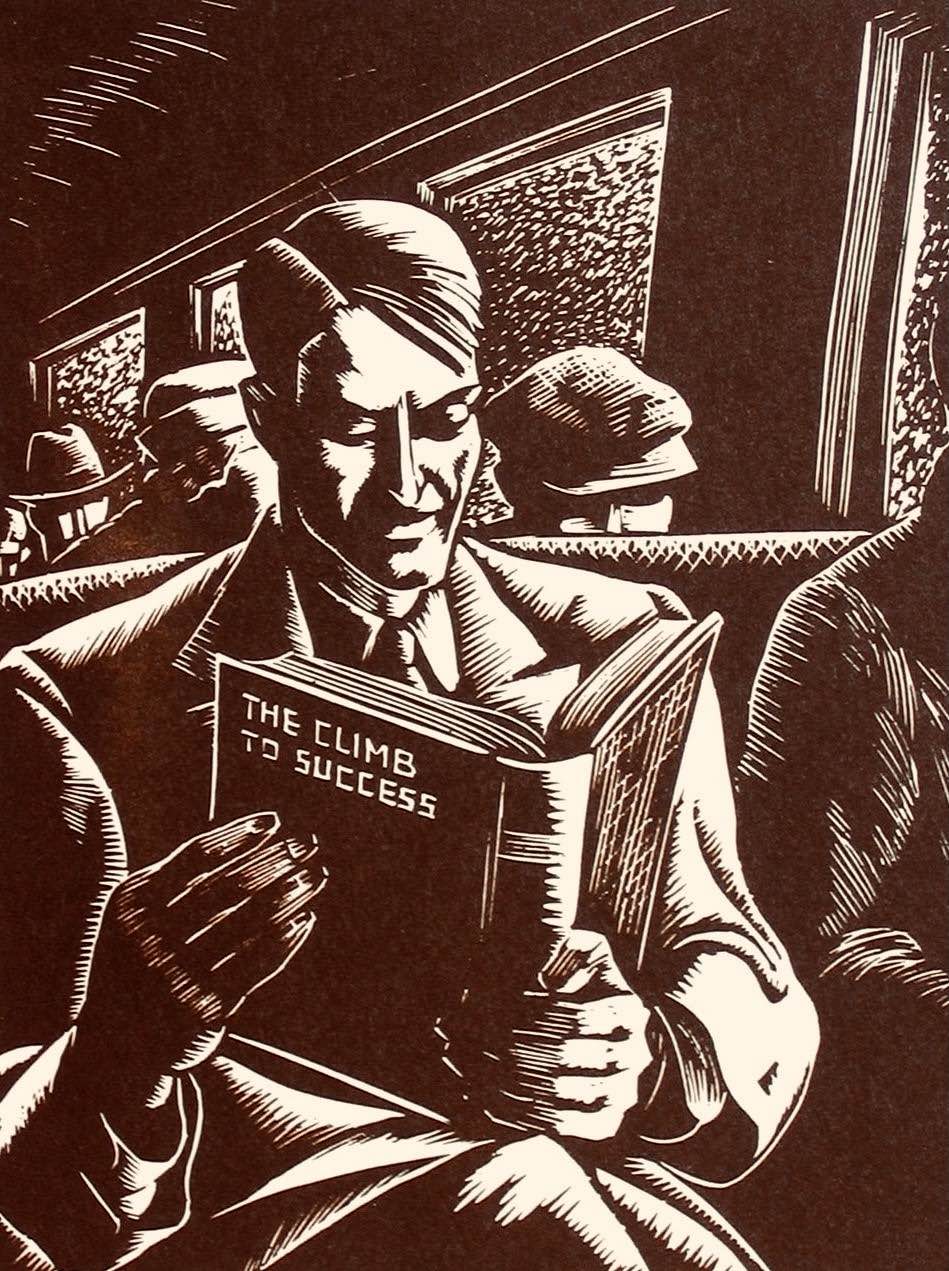

If there is any criticism to be made of the framework of mutual aid as it is currently understood, it is that it does not necessarily challenge the underlying logic of capitalist individualism. The language itself seems to presume distinct entities in some sort of exchange: “I direct my followers to you on social media and you Venmo me.”

Capitalism isolates us as competitors in a zero-sum game. With one invisible hand, it forcibly privatizes resources that were once shared; with the other, it breaks up communities, dividing us into atomized individuals with mutually exclusive needs. Today, many people have never known anything other than this. Consequently, they can only conceive of mutual aid as a means of redistributing resources among individuals, not as a way of making common cause to change our lives. But as long as everyone is pursuing an individualistic conception of wealth, there will never be enough to go around.

As long as we think of success as an individual achievement rather than the thriving of our communities, we will remain isolated and alienated, like the billionaire sociopaths we seek to emulate.

Mutual aid can be so much more than an arena in which people compete in order to supplement their wages with donations. That is symptomatic treatment—alleviating the effects of the problem—whereas we need to address the cause.

At its best, mutual aid transforms us rather than simply meeting our needs.1 It should expand our notions of what is possible and shift the ways we prioritize where we focus our energy, enabling us to solve problems collectively. Rather than contending for handouts, we need to build commons that enable us to thrive through collective practices.

Properly understood, the commons is not a discrete aggregate of resources. Rather, it is a consequence of collective behavior: commons emerge as the organic result of ways of relating to one another that do not impose artificial scarcity or hierarchies of access and control. In this regard, the commons is inherently outside the control of bureaucracy and the state.2 The extent of the commons is not determined by the quantity of resources designated as such, but rather by how effectively a given community is able to produce and share resources through egalitarian collective activity—and to defend those practices, ideally in a way that spreads contagiously.

Creating commons should also help to address a problem that has plagued volunteer groups and the non-profit sector for decades. Asking people to dedicate themselves to activism or community organizing without any compensation for their efforts generally limits the range of people who can participate in those activities to those who are already comfortably well off; but paying people money for their contributions sets up a toxic situation in which people compete for control of resources and, as in the capitalist economy, there is little incentive to do things that are not profitable. The same goes for non-profit organizations that are dependent on funding and therefore must prioritize their activities according to what the market rewards and monopolize credit for projects even when others were involved.

The solution is for collective endeavors to produce commons that benefit the participants as well as everyone else, and that have more to offer everyone the more people participate in them.

Is that really possible? Yes. Let’s look at how.

Artwork from NO Bonzo’s illustrations for Peter Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution.

The Ones with the Problem Are Themselves the Solution

The revolutionary idea at the core of the concept of mutual aid is that those who have a problem can solve it themselves by working together.

The power of this proposition is illustrated clearly enough by Alcoholics Anonymous, the classic example of an old-fashioned mutual aid society. On the face of it, the idea that alcoholics could help each other to quit drinking might strike the average teetotaler as somewhat optimistic. In fact, no one else is better equipped to assist them in quitting: no one else really understands the challenges they face, nor is anyone else quite as motivated to assist them. Millions upon millions of people have become sober thanks to this structure.

It is no coincidence that Alcoholics Anonymous is organized as a completely voluntary, self-supporting network without any authorities, means of policing, or media or political representation. The founders of the program were drawing on Peter Kropotkin’s writings about mutual aid as they designed its structure, which continues to show Kropotkin’s influence today.

“When we come into AA, we find a greater personal freedom than any other society knows. We cannot be compelled to do anything. In that sense our Society is a benign anarchy. The word ‘anarchy’ has a bad meaning to most of us. But I think that the idealist who first advocated the concept felt that if only men [sic] were granted absolute liberty, and were compelled to obey no one, they would then voluntarily associate themselves in the common interest. AA is an association of the benign sort he envisioned.”

-Bill Wilson, co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, in “Benign Anarchy and Democracy”

The “idealist” in question was Kropotkin.

Alcoholics Anonymous might seem like an outlier compared to the newer mutual aid organizations. But if anything, it is the more recent projects that have drifted from the original spirit of mutual aid societies. Like the worker cooperatives of the 1800s, Alcoholics Anonymous makes every participant a protagonist. The ones with the problem are themselves the solution.

Alcoholics Anonymous is instructive in other ways, as well. Rather than demanding that the participants have a spotless history, it begins from the premise that people can change, approaching mutual aid as a means by which to enable them to improve. This is significant in our era, in which—thanks to social media and the neoliberal economy that shaped it—we are accustomed to thinking of human beings as replaceable. Today, everyone is continuously applying, in each interaction, for employment, status, relationships, and attention—all of which can, at the first sign of friction, be snatched away and given to another contender.

Unlike money, social media reach, or a résumé, the relationships we build through mutual aid are not fungible; they cannot simply be traded in. To be worth building, then, these relationships had better be more durable and reliable than anything the market can offer. We have to see ourselves and each other as both improvable and irreplaceable. Rather than continuously evaluating each other to see who is worthy of support and who is not, we should begin from the premise that we are setting out to create a mutually beneficial context in which we can grow together and build long-term connections.

The more people earnestly participate in a mutual aid network, the better for all of the participants. Mutual aid should not be an honor reserved for the most deserving, but a transformative, contagious practice that enables people to identify with each other and conceive of well-being in collective terms.

From Seth Tobocman’s incredible War in the Neighborhood.

The Social Is the Material

In discussions about mutual aid, we often hear a dichotomy between meeting “material” needs and other kinds of activity. Some say that the important thing is to address people’s material needs, rather than engaging in political outreach or entertainment; others argue that focusing on mutual aid is a waste of time, because it is not sufficiently confrontational, or because it does not build disciplined political cadres with a shared consciousness.3

In fact, the lines between these categories are blurry. Music, social spaces and connections, ways of understanding the world and talking about what matters—all of these are essentials. People need joy, intimacy, and meaning as much as they need food and shelter, and they will often choose to go without material comforts to obtain them. It is only possible to forget this in the midst of the most vulgar sort of materialism.

This is not a new idea. Thou shalt not live on bread alone.

If we focus only on providing food and material goods without also fostering a vibrant social and political context that is rich in connections, care, and ideas, the participants in our projects will seek to meet their other needs elsewhere—for example, in churches, authoritarian political parties, or “apolitical” social scenes. A narrow concentration on the supposedly “material” aspects of mutual aid misses what is truly at stake in all of our relationships.

What counts is not just access to essentials, but what it means to access them. A feast in which all the participants play a role and eat their fill signifies We are all part of this community. Receiving a paycheck with which one can pay for rent and groceries sends a different message: “The hours that you have sacrificed have earned you, and you alone, the right to survive another month. At least—this time.”

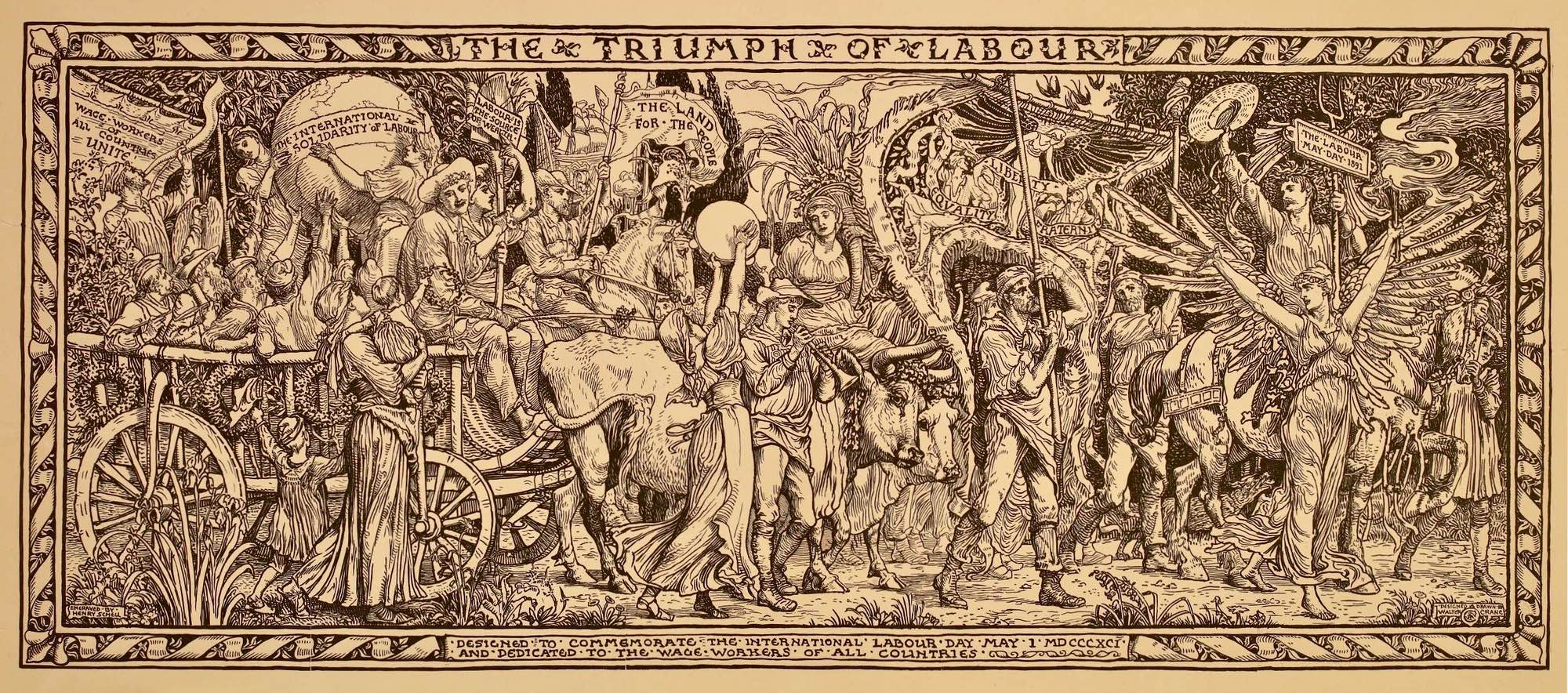

The revolutionaries who came before us imagined the triumph of the labor movement as a joyous collective holiday. A design by Walter Crane for May Day 1891.

Change from Below

So mutual aid is not a distraction from the project of changing the world; it is a fundamental aspect of changing the world, just as changing the world is necessary if we want to expand the scope of mutual aid. What’s more, the idea of mutual aid implies a model for social change that is structurally different from what Marxist-Leninists and other authoritarians propose.

When authoritarians talk about “seizing the means of production,” they mean that a top-down bureaucratic organization should seize control of workplaces and determine what goes on in them. In other words, they intend for their own leadership to make decisions for the workers the same way that bosses do—only this time, supposedly, with the workers’ best interests at heart.

There are several problems with the authoritarian framework. One problem is that even if the leaders have genuinely good intentions, they are unlikely to succeed in making beneficial decisions on others’ behalf. The best way to ensure that decisions represent the interests of those they impact is to make sure that the ones who are immediately impacted are the ones making the decisions. The more broadly agency is distributed, the more likely it is that the outcome of decision-making will address the needs of the greatest number of people. This is simply a question of information distribution: it is a matter of minimizing the degrees of alienation between those who are aware of a given issue and those who can act to address it.

Intelligence is not something that is concentrated in the head of a single genius; it is not a static quality that can be measured in isolation. It is a property of networks; it emerges in relations. The more freely information flows between different vantage points within a network and the more immediately participants in the network can act on it, the more intelligently that network will behave.

By contrast with the authoritarian model for social change, the anti-authoritarian proposal is that we establish horizontal, decentralized forms of grassroots organization that put decision-making power in the hands of those who are most immediately affected by the decisions. In place of top-down structures, this means fostering rhizomatic mutual aid networks according to reproducible models. Without the privation and pressure imposed by policing and property rights, people will naturally gravitate to the networks that meet their needs most efficiently and in the most joyous and fulfilling manner.

If we are trying to bring about liberation rather than authoritarianism, establishing mutual aid projects that can meet material needs is not a distraction from the project of decentralizing power and access to resources. Rather, it is an essential part of developing and propagating the practices via which people can engage in that project. Some call this “building the new world in the shell of the old.”

This also means that the form of these mutual aid projects matters: the dynamics that they foster between people are as important as the resources they provide. If they are unidirectional, if they only foster the agency of those on the “resource provision” side of the equation, they will not be able to plant the seeds of a new way of life.

“The fact is that human life is not possible without profiting by the labor of others, and that there are only two ways in which this can be done: either through a fraternal, egalitarian, and libertarian association, in which solidarity, consciously and freely expressed, unites all humanity; or the struggle of each against the other in which the victors overrule, oppress, and exploit the rest.

“We want to bring about a society in which human beings will consider each other brothers [sic] and by mutual support will achieve the greatest well-being and freedom as well as physical and intellectual development for all.”

–”Mutual Aid” (1909), Errico Malatesta

From Seth Tobocman’s War in the Neighborhood.

Mutual Aid Means Resistance

To sum up, then—if we want to get the most out of mutual aid, we should create participatory commons in which everyone can easily contribute and there is no fundamental division between the organizers and the beneficiaries.

At the Really Really Free Market, hundreds of people from all walks of life gather every month to interchange resources. No one keeps track of who brings what. Even those participants who have very little access to resources bring things. Anarchists set up the tables and maintain a social media page, but the vast majority of the goods that change hands come from rank-and-file participants. The majority of the participants are not self-identified anarchists, but they know that they are participating in an anarchist economic model via which they meet each other’s needs. Anarchist banners hang everywhere, expressing the political implications of this kind of sharing and declaring that more aspects of our lives could be organized this way.

Individual affinity groups or organizations can play a crucial role in activities like this—for example, by announcing and promoting them and building infrastructure to sustain them. But the best way to evaluate the effectiveness of those contributions is by asking to what extent those efforts create a situation in which others can establish a more robust relationship to their own agency. If the organizers create a bottleneck for decision-making and action, reducing others to passivity, that will not advance the project of mutual aid and liberation.

If your mutual aid project is not creating the kind of social connections, political consciousness, and collective momentum that will move us towards revolutionary social change, the problem is not with mutual aid, per se. The problem is with your project.

When people talk about “getting serious” about mutual aid, they often mean setting up an official nonprofit organization. There are several problems with this reflex.4 In the long run, unidirectional service provision will marshal fewer resources than collective efforts that everyone is invested in; we don’t want to build patronage systems that depend on wealthy donors, but symbiotic relationships based in solidarity. Formal organizations can’t carry out occupations, expropriate resources, or violate regulations—yet private property and bureaucratic control are precisely the biggest obstacles to redistributing resources on a large scale. Rather than large amounts of donations, we should seek to mobilize large numbers of participants, while aiming to expand the horizons of what we feel entitled to do to take care of each other.

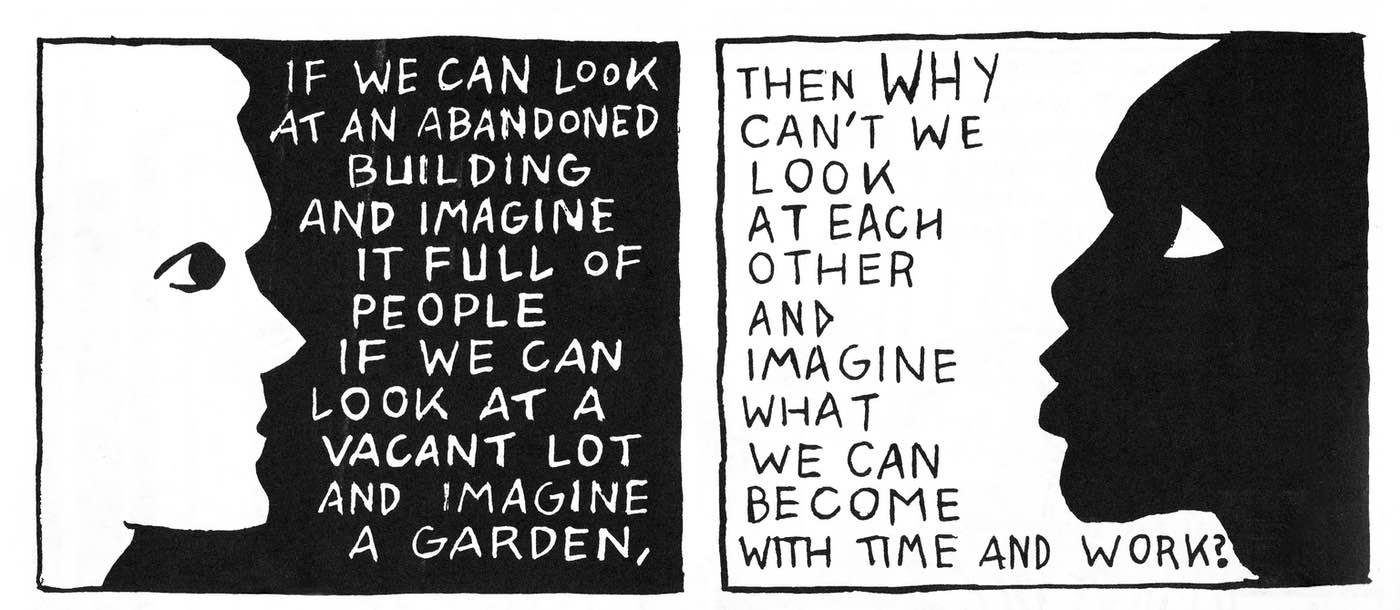

The worldwide squatting movement of the previous generation, which continues to thrive in Brazil and many other places, remains an inspiring example of what it can look like to seize privatized resources and transform them into collective power. The most powerful forms of mutual aid are the ones that enable us to revolt together, to take steps towards creating a completely different world.

A contagious gift economy with offensive capabilities and momentum towards building a completely different way of life. A combative commons that draws in more and more resources, ultimately becoming irresistible even to its enemies. This is the true promise of mutual aid.

Let the earth once again become a common treasury for all.

My liberation, my delight, my world itself begins where yours begins. Nobody can command my services because I have, of my own, pledged to give all—and to give it freely, for that is the only way to give.

Mutual aid means participatory, horizontal, decentralized, and empowering. Artwork by Jesse Lee.

Imprisoned in the Fort du Taureau, Louis Auguste Blanqui takes solace in knowing that somewhere across the ocean, the air he exhales is breathed in turn by the trees of the Brazilian rainforest, by his comrades in exile in London, even by the officials who ordered his arrest, despite their vendetta against sharing. He reminds himself that the same water his captors ration to him in a cup nonetheless crashes in great waves against the walls of the fort—that across hundreds of millions of years, every single drop of that water has passed through countless living things, traveling through the sky and back into the earth again and again. The very language with which he formulates and records these comforting thoughts has been fashioned and refined by a hundred billion tongues in a collective endeavor stretching back to the dawn of humanity. Collectivity is inevitable, ineradicable. Eventually, it will triumph over the temporary error of avarice.

-

It is quixotic to imagine that we could somehow manage our survival in an unsustainable, oppressive society in a sustainable, egalitarian way. Even in a revolutionary situation, we should not expect to be able to take hold of the existing supply chain and use it to meet everyone’s needs without making more profound changes. The same goes for the desires and values that are socially produced by the existing order: we should not take for granted that what we can imagine from this vantage point, entangled as we are in a society founded on oppression and the imposition of artificial scarcity, represents all that there could be to life. ↩

-

In place of the commons, liberals promote state-run institutions. This gives the state—the structure that presided over the original enclosure of the commons—an alibi to control resources and regulate activity in order to prevent the “tragedy of the commons.” In fact, the tragedy of the commons is simply that wherever there is a shared resource that is not available on the market, profiteers and politicians will always attempt to assert control over it or supplant it with a duplicate—and once they succeed, it is only a matter of time before the resource is privatized or commodified. ↩

-

We can make short work of arguments that people won’t revolt until things are “bad enough”—so mutual aid is an obstacle to revolution—or that mutual aid efforts give the state an alibi for austerity measures so the authorities can cut social services with the understanding that volunteer programs will take up the slack. In regards to the former argument, it is not suffering, per se, that drives people to revolt, but the understanding that suffering is needless—that something can be done about it. In regards to the latter argument, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, it should be clear that governments are prepared to permit large numbers of people to die without lifting a finger, so if we do not wish to risk being among the deceased, we have to set up what the Black Panthers called “survival programs pending revolution.” ↩

-

For now, we will set aside the likelihood that, under Donald Trump, nonprofit organizations will likely face more and more bureaucratic challenges, but it is also worth considering that the more our projects depend on the existing order, the more difficult it will be to use them against it. ↩