Escalated by police violence, a protest movement in Nepal snowballed into a spontaneous insurrection, culminating on September 9, 2025 with the toppling of the government. To follow up our interview with Black Book Distro in Kathmandu, we sought more context for the conditions that produced the revolution and the forms that it has assumed from a Nepali journalist currently located in Portugal, Ira Regmi.

On September 8, 2025, Nepal witnessed a revolution as thousands of predominantly Gen Z youth took to the streets in protest. This collective action was met with brutal state repression, resulting in a mass slaughter of protesters and working-class students in school uniforms. The current death toll stands at 74, including three police officers and approximately 10 incarcerated individuals.

The movement’s broader cause was rooted in opposition to corruption; it can be understood as the culmination of the 2019 youth-led “Enough is Enough” movements. The immediate catalyst for this action emerged when Gen Z activists initiated a social media campaign exposing the lavish consumption of political elites’ children, arguing that such lifestyles were subsidized through public funds. The hashtag #Nepobaby quickly gained traction across digital platforms and the government’s subsequent censorship, which blocked 26 social media platforms, catalyzed widespread protests. Only five registered platforms remained accessible: Viber, TikTok, Nimbuzz, WeTalk, and Popo Live. Content creators reported that TikTok and other platforms were actively suppressing anti-government criticism. This repression intensified consciousness, propelling organizers to leverage alternative communication channels and to circumvent state censorship by using VPNs, accelerating the mobilization beyond the regime’s capacity to suppress it.

In a solemn act that marked the beginning of revolutionary justice, the newly formed caretaker government led by Prime Minister Sushila Karki officially declared the fallen protesters to be martyrs of this struggle. The state honored the deceased with a dignified national cremation ceremony and proclaimed September 17 an official day of national mourning. Their blood sanctioned the birth of a new Nepal, and their memory shall forever inspire revolutionary transformations across the world. However, the public has made it clear that commemorations alone are insufficient and further accountability for state violence remains non-negotiable.

The Gen Z movement in Nepal represents a fundamental departure from the post-2006 political settlement that governed the country since the monarchy’s formal abolition and has evolved into a significant challenge to the structural foundations of Nepal’s institutionalized corruption.

This article examines the material conditions behind this mass mobilization and interrogates the constitutional, political, and social questions it has brought to the surface. Detailed explanations of the exact course of events can also be found in the accounts of independent journalists and social media content creators.

Photo by Sulav Shrestha.

State Violence, Revolutionary Response, and Capital as Target

The violence began, as it always does, with the state. The government escalated peaceful protests through brutal repression, firing indiscriminately into crowds, shooting lethal bullets directly at the heads and chests of young people in school uniforms. This brutality, which caused the single highest death toll in a day for protests in Nepal, was not isolated. It represented the systematic violence through which the Nepali state has maintained power in recent years, regularly suppressing dissent through lethal force.

The following day, the accumulated rage of the people manifested as direct action against the symbols and infrastructure of power and capital. Protesters targeted public institutions including the parliament, government administration buildings, the reserve bank, and the supreme court. The homes and businesses of political and business elites were also pointedly targeted. Kathmandu valley turned black with smoke as protesters unleashed the material manifestation of revolutionary rage—an embodiment of “burn it all down” that transformed the capital’s skyline into a canvas of defiance.

Among the targeted businesses, Choudhary Group, NCELL, and Bhatbhateni supermarket chain suffered significant damage, with 12 of the 24 Bhatbhateni outlets destroyed. The business tycoons swiftly issued statements emphasizing their resilience, but notably absent was any meaningful introspection regarding why they specifically became targets of public rage.

The widespread targeting of Nepal’s millionaire class, coupled with liberal objections to property destruction, shows the importance of radical anti-capitalist analysis within this historic uprising. The industrialists targeted by the masses stand thoroughly exposed as class enemies of the revolutionary youth, as their wealth has been built upon a foundation of exploitation and corruption. The Choudhary dynasty faces allegations of concealing assets in Panama tax havens, orchestrating insurance fraud schemes, and illegally seizing state-owned factories. Similarly, Min Bahadur Gurung, the owner of the Bhatbhateni empire, has participated in the theft of public lands and committed VAT evasion totaling approximately 1 billion Nepali Rupees. NCELL was involved in the largest tax evasion and money laundering scandal in the country. The entanglement between private capital and Nepal’s corrupt political apparatus—where wealth purchases policy and protection—demands ruthless critical examination, as does the fundamental immorality of such obscene wealth accumulation.

While counter-revolutionary provocateurs undoubtedly participated in these events and warrant rigorous analysis and investigation, much of the destruction of public and private property stemmed from genuine public outrage. Urgent demands for de-escalation following the prime minister’s resignation were critical, especially as conclusive evidence now confirms that violent pro-monarchist and legacy party factions deliberately instigated most of the chaos during the latter half of September 9.

However, we also witnessed unmistakably bourgeois hand-wringing over property damage that is indicative of the class character of such critiques. The liberal impulse to equate destruction of capitalist property with violence against people constitutes a profound mischaracterization of revolutionary praxis and masks the true nature of violence committed against the Nepali people.

Photo by Sulav Shrestha.

The Specter of Corruption

As independent journalist Pranay Rana writes in his newsletter Kalam Weekly, “The campaign reflected a broader frustration with the status quo” and emerged from the systemic nature of public corruption in Nepal. Some major examples of corruption scandals have included the fraudulent registration of Nepali citizens as Bhutanese refugees for third-country resettlement; irregularities in contractor assignment for the construction of Pokhara International Airport; systematic transfer of public lands to private entities; and the electricity distribution scandal where authorities provided uninterrupted power to commercial interests while subjecting the general population to up to 18 hours of daily power outages.

But the issue of corruption was always more than just large scandals involving high profile political elites. Corruption permeates civil society through normalized bribery across professional environments and through the systematic distribution of institutional appointments from ministerial positions to university chancellorships based on patronage networks rather than merit. These conditions resulted in profound alienation among the masses. Throughout Nepal’s professional, industrial, and bureaucratic spheres, corruption visibly erodes society like rust eating through metal.

The former administration under KP Oli further accelerated this alienation by exhibiting increasingly authoritarian tendencies masked by hypernationalist rhetoric. Meanwhile, so-called opposition parties colluded with the parties in power to establish a revolving chair system of governance—a cynical arrangement where they agreed to rotate executive leadership amongst themselves, fundamentally hollowing out any pretense of democracy.

Photo by Sulav Shrestha.

Revolutionary Praxis Meets Constitutional Crisis

The tension between bourgeois constitutionalism and revolutionary necessity emerged as the central contradiction in this struggle. A generation of predominantly teenage and twenty-something activists confronted profound constitutional questions within mere days, while established legal scholars largely dismissed revolutionary imperatives as fundamentally unconstitutional.

Nepal’s constitution—itself the product of a mass movement, albeit one led by political parties—represents a crystallization of political compromise that established a formal democratic order. However, this constitutional framework betrays the limited imagination of its architects, who were largely members of legacy political parties as well as an intellectual elite that perhaps never envisioned (or did imagine and wanted to avoid) a scenario in which popular legitimacy might transfer away from their rule. Consequently, the document lacks modalities for establishing interim governments when political conditions demand them. This structural absence reveals that the primary function of the constitution was to regulate elite competition rather than to facilitate authentic popular sovereignty.

A fundamental impetus behind this revolution was the complete erosion of trust in both the executive and legislative branches of government. Yet any strictly constitutional pathway, as defined by legal elites, would necessarily involve the legislature—the very institution whose dissolution emerged as a core revolutionary demand. As written, the constitution prioritizes attempts to form a government from within the existing parliament through some combination of the following steps: 1) Over 50 percent of parliamentarians support dissolution, 2) Either a formal parliamentary session or the executive recommends dissolution to the president. Empirical reality, however, rendered these pathways impossible. The executive branch and most of the 275 Members of Parliament stood implicated in systematic exploitation and corruption, bound by class loyalty to the parasitic political establishment that the people had righteously overthrown.

Consequently, the movement advanced an interpretation of constitutional legitimacy that challenged the ruling class’s monopoly on its meaning, empowering the people to establish a caretaker government while dissolving the parliament. Young legal scholars correctly identified multiple interpretive pathways through which a caretaker government could be established without wholesale constitutional abandonment. They reminded the people and senior advocates that the constitution exists to serve the people, not to trap them in a corrupt system.

The timely work of public education and advocacy by Advocate Ojjaswi Bhattarai along with a group of other young scholars and internet influencers enabled the movement to maintain constitutional continuity. They advocated for these interpretations by invoking a doctrine that allows for specific parts of a constitution to be temporarily rendered inoperative (or “eclipsed”) when extraordinary circumstances make their normal application impossible. They also argued that since the revolution unambiguously channeled the collective will of the people, this will could supersede other formal legal imperatives. There was no doubt that the movement clearly demonstrated a popular mandate for both forming a caretaker government and dissolving the parliament, grounding their constitutional reinterpretation in genuine democratic legitimacy.

Schoolchildren pass the charred remains of a public bus in Kathmandu on September 15, 2025, the day the schools reopened. Photograph by Narendra Shrestha.

Democratic Experiments and the Battle for Narrative Control

These legal and strategic discussions unfolded primarily in digital spaces, yielding unprecedented forms of democratic praxis. Over 120,000 Nepali youth mobilized through Discord to collectively determine the interim Prime Minister candidate—a radical experiment in direct democracy with the masses creating new organizational forms beyond the constraints of bourgeois political structures. Following the nomination of Sushila Karki, youth collectives initiated both digital and in-person town halls to chart the path forward.

At present, multiple groups are coalescing to articulate a formal revolutionary mandate with concrete demands and the means to establish new institutions of accountability that authentically serve the people’s interests. There also are anarchist groups working hard to build solidarity across the Nepali left and are committed to organizing outside traditional norms of hierarchy.

This democratic experimentation through digital platforms presented challenges even for the revolutionaries—including state surveillance, digital repression, infiltration, and the tendency for these platforms to become propaganda machines that derail the expressed will of the people. This exercise constituted such a fundamental rupture with liberal democratic norms that participants naturally experienced some initial disorientation.

Additionally, as writers of the Cold Takes by Boju Bajai newsletter point out, the existing corporate media apparatus struggled profoundly to interpret these developments, as many senior journalists lacked even basic familiarity with platforms like Discord. As Kantipur TV continued broadcasting against the backdrop of their incinerated corporate headquarters, media conglomerates also revealed their class character through their persistent coverage of obsolete political formations, failing to grasp that the material conditions for discourse had fundamentally transformed overnight.

A contrast emerged between the revolutionary consciousness developing among youth on Discord and Instagram versus the reformist tendencies prevalent on platforms like Facebook and Twitter. The bourgeoisie and older generations, who had monopolized political discourse for decades, experienced confusion from this transformation, unable to comprehend that their hegemony over political expression had decisively been broken.

At the same time, while this digital revolution amplified previously marginalized youth voices, it was also exclusionary, leaving behind older generations and those lacking technological access.

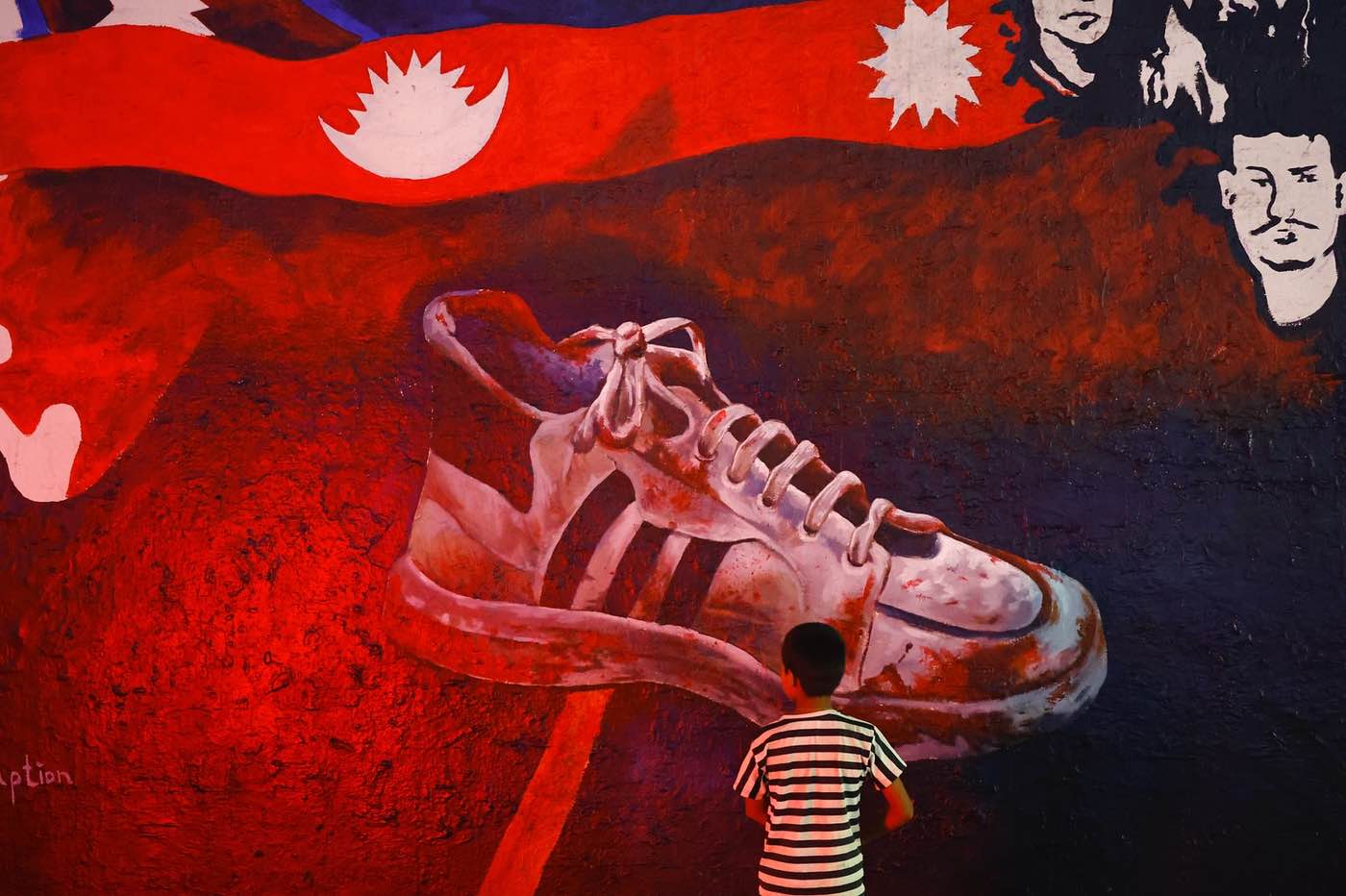

A boy looks at a mural made by artists Riddhi Sagar and Somic Shrestha, depicting the white shoe of 28-year-old Prakash Bohara, who was shot during the protests in Nepal. Photograph by Skanda Gautam and Sahana Vajracharya.

Radical Inclusion Means Class, Caste, Gender

While this revolutionary movement represented a significant rupture in the political order, educators and activists like Ujjwala Maharjan, Anjali Shah, and Tasha Lhozam have pointed out that it remains incomplete without addressing the fundamental contradictions of caste, class, and gender that structure Nepali society.

To critique corruption without interrogating the inherent immorality of capital accumulation is to mistake symptoms for disease. The political class now under attack for nepotism and corruption have inevitably attempted to launder their obscene wealth as legitimately earned with the help of bourgeois orthodox economics. This counter-revolutionary maneuver can only succeed if the revolutionary movement fails to confront the uncomfortable truth that many aspirations within its own ranks remain contaminated by capitalist fantasies of individual advancement within existing structures. Without a critique of capitalism itself, this revolutionary moment risks slipping into mere reformism.

A truly revolutionary consciousness must synthesize anti-capitalism with militant opposition to caste hierarchies and patriarchal subjugation while upholding an abolitionist perspective. We must never forget that among the deceased were incarcerated youth whose deaths at the hands of state forces while attempting to escape brutal conditions of confinement constitute class murder. The very concept of juvenile detention centers represents the individualization of social problems. Crime itself must be understood not as individual moral failures but as the predictable outcome of material conditions created by social relations. The impulse to rehabilitate institutions of state violence—exemplified by those who rushed to restore police infrastructure—reveals lingering ideological contamination from respectability politics. Revolutionary humanism demands the abolition, not the reform, of these carceral institutions.

Finally, the spontaneous proliferation of trans and queer flags across the Discord server revealed the movement’s latent progressive character. This movement, though presenting a unified front, contains within it diverse material experiences—Indigenous peoples, caste-oppressed communities, and sexual minorities whose specific forms of exploitation must be articulated within a coherent revolutionary program. The historically privileged elements of the movement—cis, straight, male, upper-caste youth—must engage in ruthless self-criticism regarding their accumulated privilege. Only through this process can an intersectional anti-capitalist vanguard emerge from this historic moment of mass radicalization.

The upcoming elections demand that Nepali people rally behind a non-legacy party that genuinely champions Gen Z’s revolutionary vision and directly confronts the entrenched apparatus. Only by securing a parliamentary majority can the youth break free from the corrupt political landscape. Failure to achieve this majority risks condemning Nepal to decades more under the same ruling class.