It is the beginning of April and the mental impact of the lockdown has become even more surreal as the seasons change. The acts of resistance over the past few weeks have been both beautiful and terrifying. Meanwhile, the government continues to restrict our freedoms while opening Greece to tourists and business—in spite of infection rates averaging between 3000 and 4000 cases of COVID-19 a day, putting Greece third to last in the EU in terms of managing the crisis. In the following report, we describe the conclusion of the hunger strike of Dimitris Koufontinas, the clashes of March 9, and more.

This report is brought to you by anarchists on the ground in Greece. You can read our previous reports from Greece starting here. A full list of resources on struggles in Greece is included at the end.

Dimitris Koufontinas: Resistance from an ICU Bed

We are happy to report that Dimitris Koufontinas, a November 17 political prisoner of the Greek state, is still alive after surviving a 65-day hunger strike. The state has repeatedly rejected his demands to be moved back to the prison where he has spent the majority of his sentence, closer to his family, despite Dimitris’ potentially fatal hunger strike. He ended his hunger strike following pressure from his family and certain political groups, acknowledging that he had exhausted every legal option available. Though he will face permanent health consequences, he inspired many to take to the streets or to the night.

Koufontinas did not achieve his demands, though all he was asking for was his supposed legal rights. This was unlikely all along, especially under this administration, which is directly descended from the same authoritarian dynasty Koufontinas fought against. We celebrate his act of defiance and the catalyzing effect it has had for other rebels. In our last report, we explained our political differences with Koufontinas, who has never been an anarchist; at the same time, it is important to express solidarity with him as a struggling political prisoner.

Every day for weeks, small groups of courageous people took the streets in support of Koufontinas; despite their small numbers, they faced the kind of police brutality—water cannons included—usually reserved for riots. The protests grew in size as it became increasingly obvious that the state was prepared to let Koufontinas die. The tensions arising from both the COVID-19 pandemic and the government’s opportunism in using it to accelerate their repressive agenda contributed to setting the stage for this moment. But this last stand by a well-known political prisoner was what forced thousands of people to overcome their fear and come out of lockdown.

https://twitter.com/exiledarizona/status/1368111955043627009

Demonstrations took place every day. An ungovernable force emerged; both sides knew that if the police pushed things too far, it would cause an explosion. If one day saw smaller numbers, the police would take the opportunity to attack, only to see numbers multiply the following day. Nighttime actions expanded alongside the daily demonstrations. Over five hundred attacks occurred, targeting municipal buildings, police stations, right-wing media outlets, and even the personal cars of police at their homes. With police focused on the central demonstrations and unsure where people might strike next, the attacks became so frequent that private security were hired to guard the homes of prominent politicians and businessmen.

Anarchists, autonomists, students, anti-fascists, lawyers, extra-parliamentary and even parliamentary left groups marched side by side against the effort of the New Democracy government to mark the end of an era with the death of Koufontinas. They wanted to set the precedent that those who step out of line in the struggle against authoritarian institutions will die in prison, along with their dreams and the movements they represent. Yet the administration did not expect such a passion to manifest. The media was struggling to cover the clandestine actions without referencing the hunger strike that motivated these courageous acts. They tried to argue that the demonstrations were spreading COVID-19 while concealing the reason people were in the streets. Still, thousands took to the streets of Athens behind a banner reading “I was born on the 17th of November.”

A demonstration in solidarity with Dimitris Koufontinas.

In Athens, Thessaloniki, Patras, and elsewhere around the country, people mobilized despite the risk of arrest, fines, and detention. Protestors communicated that they were willing to risk their health and safety rather than forfeit their freedom. The massive demonstrations communicated that we do not mourn the relatives of the current junta, that we will not permit the ruling class or its media to present them as victims. Most importantly, they showed that those suffering and struggling against domination and exploitation behind bars will not be forgotten, that “the passion for freedom is stronger than their prison cells.” Despite the isolation of lockdown, there are many of us, and we are ready to ride the next wave of revolutionary tension against the state and capitalism together.

As a consequence of the hunger strike, Koufontinas’s kidneys nearly failed; he was forced to receive dialysis. This being his fifth and longest hunger strike to date, he suffered significant deterioration of his health that will have long-term effects. It is a remarkable and inspiring feat that he survived for so long on nothing more then a vitamin serum and his own integrity and motivation.

Koufontinas’s demands were absolutely within his legal rights. We do not recognize the state’s so-called justice system, nor expect anything just from it. After the media and state apparatus were forced to respond to domestic and foreign political pressure, they needed to claim that Koufontinas had not followed the appropriate protocol to present his demands, claiming that it was absurd he would turn to a hunger strike. “If we give into his demands, we will have to do the same for rapists who will starve themselves the next time they want something,” said Sofia Nicholau, the Trump-loving Greek Minister of Prisons, once the hunger strike became a scandal she could no longer ignore.

Koufontinas’s lawyers went public after Nicholau’s statement, announcing that they had already pursued the legal route multiple times, and that they would return to the courts to contest the state’s refusal to honor Koufontinas’s rights. His lawyers attempted to appeal the decision of his new transfer, as well as to make the case that returning him to the prison of Korydallos in Athens would protect his health and calm the situation. The lawyers updated the public throughout the appeals, given the feeling that there could be a looming civil war if Koufontinas died. All the judicial avenues that the government claimed the lawyers had not tried, the state had actually rejected, pushing Koufontinas closer and closer to death. Fortunately, Koufontinas is a revolutionary, not a martyr. He was informed of the achievements of his strike; once the deceptions of the courts and the administration were exposed in regards to his supposed rights, he chose to stop his hunger strike.

The forms of state repression that political movements have faced in Greece have varied throughout the years, but they have only become comparable to those in countries like the United States since the New Democracy government assumed power. The Greek state is hurrying to modernize its tactics via a permanent offensive against political opponents that includes technological advances, so-called “quality of life” policing, and intensifying investigations and punishment through the creation of new anti-terror laws. New Democracy is communicating that nothing will stop them from enforcing this new status quo. This is a wake-up call to revolutionary movements here: we must adapt and grow accordingly, to ensure that this repression cannot crush the possibility of resistance.

https://twitter.com/exiledarizona/status/1370083252954931206

March 9: The Clash in Nea Smirni

The demonstration against police violence on March 9 created a new situation nationwide, enabling us to breathe more freely on the streets and in the squares of Athens. We understand these events in the context of the resurgence of resistance sparked by Koufontinas’s hunger strike, the constant student demonstrations, and the relentless police repression, but they deserve recounting in detail.

The demonstrations in the center of Athens in solidarity with Koufontinas were unrelenting, growing day by day, as we believed that his death was drawing closer. The movement was already putting its foot out the door, testing the waters to discover what was possible amid the lockdown; it was time to start wading through. Protesters showed up despite the risks; society at large was also tired of this continuing authoritarian experiment. While ICUs filled and infection rates soared, it became clear that there was no logic to the controls that police were forcing on us, despite media attempts to scare us all into unquestioning acceptance. What happened on March 9 in Nea Smirni was undoubtedly a product of the broader tensions simmering across the country, and it illustrated what it means for a revolt to generalize beyond the typical protester demographics.

The weekend before March 9, police conducted checks on families in a popular square to see if they had sent the proper SMS to the state telephone service or could provide paperwork showing they had the right to be outside in accordance with COVID-19 mandates. Officers harassed one family, writing a 300-euro ticket simply for sitting in the square. Then the police brutalized a man who spoke up against this; fortunately, someone caught this on video. Eventually, they arrested him and continued their abuse off camera. At first, the police claimed that they captured the man after 30 people had attacked them. The media pushed this narrative, but it turned out to be a blatant fabrication. The original video went viral, undermining the narrative that the media had spread.

Police have taken advantage of the excuse of the lockdown to perpetrate this sort of violence constantly in Athens and across the country. In diverse neighborhoods such as Kipseli, as well as areas like Exarchia that are deemed anti-cop zones, police harass people of color, immigrants, and refugees without fear that anyone will speak up for their rights or courts consider their pleas. Without dismissing the brutality and authoritarianism of the officers, it is likely that the video of this beating and the reports of police harassment received mainstream media coverage because Nea Smirni is a middle-class, predominately white Greek neighborhood. What was caught on camera was considered evidence of police wrongdoing only because the victims were the sort of people that the police exist to protect. Therefore, the media—which had ignored demonstrations in the thousands and instances of brutality condemned by the likes of Amnesty International—had no choice but to publish the images of this man being beaten and police without masks screaming in the faces of families for violating lockdown.

Leftists, community organizers, and anarchists called for a demonstration against the police in the main square of Nea Smirini, where the video was filmed. This demonstration was distinguished from those in Propylea and Syntagma in the city center by the participation of massive numbers of people from the neighborhood. It is estimated that ten thousand people were in the square for this march, with formal organizations accounting for only part of that number. Anarchists were present and ready to fight, but so were grandparents, teenagers, and children from the neighborhood who were sickened by the assault.

The police were on the defensive, as the violence in the viral video could not be denied, and the eyes that were opened through watching it could easily wander to countless other accounts of brutality, repression, and torture. Many joined the demonstration assuming that the police would keep their distance, especially as left and right media outlets hinted at signs of a repeat of 2008 if the police didn’t show restraint. In a calculated display of tolerance, MAT and Delta police used for crowd control were stationed near the demonstration, but in a defensive position at the nearby police station and mobile command posts. We assumed that the police wouldn’t fuck around and find out, and the gigantic demonstration would be just that: a demonstration.

The police did not expect such a huge number of locals who do not normally attend demonstrations. They also did not anticipate the unprecedented collaboration between hooligan clubs such as AEK, Atromitos, Panionios, and Olympiacos, all of which informally united against the police and joined the demonstration. The animosity against the police was enough to rally those who typically cannot even sit near each other without stabbing one another. The hooligans brought an exciting and spontaneous strength to the gathering in Nea Smirni; alongside anarchists and anti-fascists, they reshaped the expectations of the demonstration.

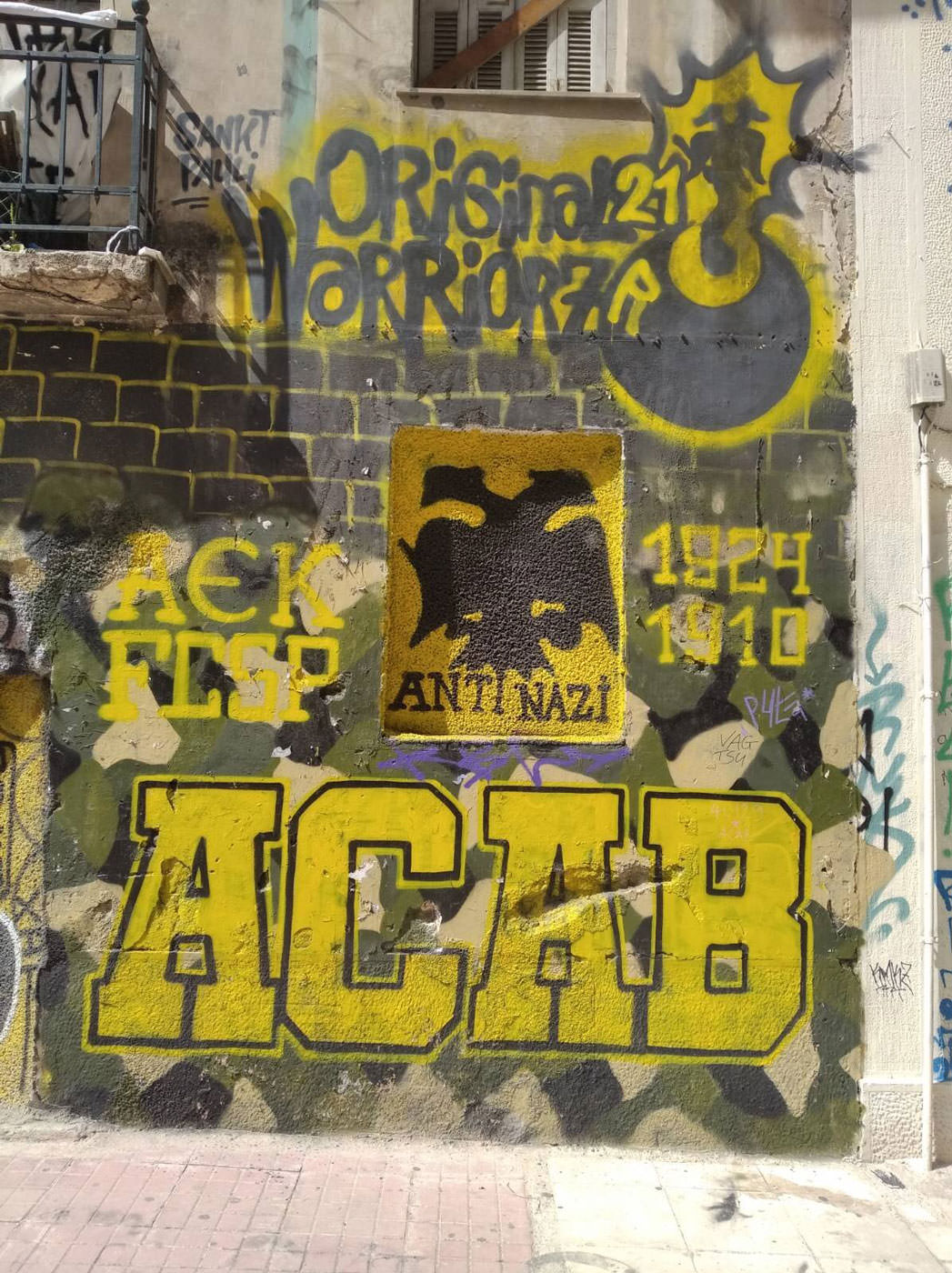

Graffiti on the AEK club in Exarchia, beside the memorial to Alexandros Grigoropoulos.

While police kept their distance, local residents, anarchists, and hooligans took the march to the local police station. They clashed with riot police and tear gas, then attempted to move towards the local mayor’s office, at which point the police began charging the crowd on motorbikes. The march broke up into roving groups of angry residents, hooligans, anarchists, and anti-fascists. Blocs of individuals carrying sticks, rocks, flares, Molotov cocktails, and whatever else they could find took over the streets. Many small battles went unreported, from families throwing rocks at the local police station to police throwing Molotov cocktails at demonstrators—but one revolutionary moment was caught on video.

A team of Delta police were using their motorbikes to charge rioters at a nearby highway entrance to Nea Smirni. Hundreds fled, yet one individual could be seen running forward—that one spark that can start the proverbial prairie fire. This courageous individual ran towards the Delta police and grabbed one officer from his motorbike, throwing him to the ground. Instantly, dozens more rushed courageously toward the police. The other Delta police abandoned their colleague and fled. This is not surprising, as their bond is produced by a paycheck while our connections are inspired by the passion for freedom. The officer was beaten, but the assailants consciously spared his life. Though the police tried to keep distance on March 9, they had reaped what they sowed via innumerable harassments and assaults.

https://twitter.com/815_1979/status/1369591964182732806

https://twitter.com/s_txvd/status/1369359007580880907

People retreated, despite the police abandoning their own. Police across the city responded with a wave of terror targeting Nea Smirni. Video footage of the announcement on their radios showed police rallying and screaming “We will kill them all,” though some TV channels adjusted this to “they will kill him” to protect public image.

The police arrested people at random that night. They beat teenagers mercilessly and raided people’s homes and stores, treating everyone in the neighborhood as a target. One teenage girl who couldn’t bear to watch her friend being beaten by Delta police tried to intervene, only to be beaten and threatened with rape. Videos filmed throughout the night appeared online, showing the nature of the police, while many arrests took place that night and over the following days. An “anti-terror” task force arrested a participant in the activist collective Masovka outside a social center; you can view an interview with a member of this collective about his arrest and torture here.

https://twitter.com/partizanGreece/status/1369381093745561601

https://twitter.com/amfetamini/status/1369349989399474178

Police have arrested several people from hooligan clubs in alleged connection with the beating of the Delta cop, notably including an Iraqi-born hooligan from the team of Olympiacos. This arrest was carried out solely based on the testimony of a troubled relative of the arrestee, and apparent video evidence that this individual was at work at the time in an entirely different region has since become public. Yet despite multiple sources of evidence that this person wasn’t even in the area at the time of the event, he remains in prison—and likely will until the police find someone else to blame.

The prime minister went on television to mourn the injured Delta cop, pleading for unity while dismissing the police brutality that had provoked the demonstration. Right-wing press attempted to cast police as victims in order to excuse the behavior of the police, implying that one officer down is worse then an entire society living in constant fear. Nonetheless, demonstrations took place in neighborhoods across the country as people everywhere came together against the police. It wasn’t possible to create a media narrative depicting isolated events, as even suburbs saw the kind of demonstrations that are usually typical only of anarchist groups in the center of Athens.

Repression continues to this day. However, with the exception of a few rebellious neighborhoods like Exarchia, immigrant neighborhoods, refugee camps, and prisons, the police have been forced to take a step back—undoubtedly as a result of people uniting against them.

Hooligans provided considerable strength to the March 9 demonstration. It was not simply anarchists in the videos we saw that day, though they were a significant force in the streets. Likewise, this was not an isolated event; hooligans have contributed to various revolutionary moments in Greece, especially the uprising of December 2008. Personally, we have some criticisms of the culture associated with hooliganism. We are critical of the psychology of micro-nationalism that lies at its foundation, and the associated misogyny and sexism. Especially in Greece, the relationship between mafia, business elites, and hooligan clubs is obvious. Yet we should not dismiss hooligans out of hand. This milieu, originally born of poverty, which has despised the police from the beginning, deserves our consideration.

In Greece, athletics are accessible to all from an early age—much more so than punk rock or hip hop, for example, which provide many people an introduction to politics here. Unlike in the United States, where youth culture has been depoliticized, professional sports and hooligan clubs play a major part in Greek society and many people’s politicization, for better and for worse. You cannot walk around the cities or even the countryside in Greece without seeing hooligan graffiti—including anti-fascist, anarchist, or fascist and nationalist graffiti alongside club tags. Many young people find identity and community in hooligan and sports clubs from an early age, and subsequently discover politics and conscious contempt for certain institutions through this experience.

For example, AEK, a mainstream sports team on par with the US NBA or NFL, has a larger presence of anti-fascist fans, while teams such as Olympiacos tend to draw more fascist fans. There are fascists and anti-fascists in both clubs, but the point remains that hooliganism is a gateway to politics for many, despite all its flaws. When you think about the school shootings in the USA involving alienated youth who are unable to find community or any outlet for frustration, it may be that hooliganism or fan clubs represent a healthier outlet for existential dread. Throughout history, sports have been used to perpetuate spectatorship and protect the status quo; again, for better and worse, hooliganism has sometimes challenged this. In any case, on March 9 in Nea Smirni, these clubs shared the joy of solidarity and revenge with anarchists and other residents.

Grappling with the potential and flaws of hooliganism as a presence alongside the anarchist movement in Greece, we are reminded of the words of Alfredo Bonanno:

“It is never possible to balance liberatory violence with the conditions of struggle. The process of liberation is excessive by nature. In the direction of overabundance or in that of deficiency.”

Students

Hoping to suppress a tradition of university asylum nearly fifty years old, the government continues push police onto campuses. This is taking place alongside efforts to privatize education, destroy movement infrastructure, and modernize the country according to a neoliberal paradigm. Yet students and other young people continue to take to the streets, expressing that police will never be welcome on campuses or in schools. As of now, the schools remain closed, so it remains a hypothetical fight, but the stakes will be concrete very soon.

Cat-and-mouse occupations continue at universities across the country. Students will occupy a building, lose it in a police raid, then occupy another building the following day. The university headquarters in Thessaloniki has become a sort of autonomous zone, having been raided and reoccupied multiple times. It remains resilient, in the spirit of the student struggles from which it emerged, demonstrating how communities can remain safer without the police. It has been used as a community resource center, providing free classes, skill shares, and various other mutual aid efforts.

Student demonstrations across the country continue despite COVID-19, and are expected to intensify as lockdown is eased and the state’s new campus policies are put to the test as schools re-open.

https://twitter.com/chris_avramidis/status/1369018074205130755

The Lockdown

It is degrading to witness the state’s desperate attempt to reopen ahead of the upcoming tourist season despite record infection rates. All these months of living in purgatory, with our “freedoms” measured according to the state’s capitalist definition of survival, are coming to an end so they can open up the country like a zoo.

The failure of their policies is obvious, whether in the contradictions of government mandates or the tragedy unfolding in Greek hospitals. The state has been put on the defensive. Yet the government continues to gaslight the population, arguing that the failure of these measures is the fault of citizens who did not follow them correctly.

Watching the authorities preparing to force the re-opening of retail and tourist attractions when infection rates are at their highest ever, one must ask if they are trying to push the peak higher in order to set a plateau that is more welcoming to tourists. This is just speculation, but it makes more sense than anything being spouted in parliament.

While the state pushes to reopen up for tourists, medical workers are demonstrating outside hospitals and the Ministry of Health, demanding PPE, ICU facility expansion, and the addressing of other basic needs related to this medical crisis. Members of the MAT riot squad—which, like the rest of Greek law enforcement, has enjoyed heightened salaries and budgets at the expense of hospitals and their staff—brutally attacked a recent demonstration by medical workers.

https://twitter.com/velocity2121/status/1376899506235707394

In contrast to the United States, there is little effort to recognize essential workers as “heroes” here. In the US, efforts to celebrate delivery workers, grocery workers, and medical workers seem to be part of a capitalist strategy to create a war narrative, awarding “hero” status to certain workers while keeping their salaries low. In Greece, there are efforts to glorify the police and military during COVID-19, and their budgets have been increased—despite their serving no tangible role in addressing the pandemic. Meanwhile, delivery workers, grocery workers, medical workers, and other essential laborers are considered fortunate to have a job at all during this time. They face harassment, violence, and the wrath of the state if they demand anything more then the privilege of employment.

No lockdown that divests from hospitals to expand police and military budgets is truly aimed at protecting people’s health. Such a lockdown can only be an experiment in authoritarianism. Following the generalized revolt in March, police have passively stepped back from enforcing the lockdown. Everyone has witnessed how the government has taken advantage of the virus to push new policies and restructure everyday life. While many people recognize the disastrous impact that a spike in COVID-19 can have on hospitals and the vulnerable, most have simply become jaded.

Of course, police still run rampant in Exarchia and chase people of color to impose lockdown fines and detentions, but most people simply don’t care anymore and act accordingly. What other reaction is possible when German tourists are landing in Crete for holidays while those who live here are forbidden to travel more then two kilometers from their homes?

To put it simply, the government has failed. It blames those it rules over for its failures, but its entire existence is rationalized by the notion that it can protect us from ourselves and from unprecedented events. Yet it has not protected us—it has failed to protect us. This is further proof that the state is a mere nuisance, if not a scourge—that it exists only to preserve a status quo that benefits a privileged class at everyone else’s expense.

Repression

Since New Democracy came to power, the Greek state has been doubling down on repressing anarchist militants. However, despite fear, our movement remains strong and resilient, with a firm and broad solidarity. Fines, arrests, detentions, lengthy trials, and fabricated anti-terror cases are unrelenting, yet the movement continues.

The situation in Greek prisons continues to deteriorate, due both to COVID-19 and to the Minister of Prisons Sofia Nikolaou using additional funding to inflate staff salaries rather than securing the safety of prisoners. While many court cases are ongoing, we want to highlight a few in particular.

Errol, an anarchist born in France who was captured on December 6, was held in an immigrant detention facility and deported to France without trial, contrary to his legal rights in the European Union. He was able to make his way back to Greece, amazingly. Errol’s case represents an unprecedented move by the Greek state. Regardless, Errol was arrested again following an anti-racist rally in Athens and placed back in the immigrant detention facility known as Petrou Ralli. He was released following his detainment on March 29 and given 30 days to leave the country or face further legal proceedings. His courage in spite of the Greek state’s attempts to get rid of him is inspiring.

Meanwhile, the trial of anarchist comrade Vangelis Stathopoulos, accused for participation in the “Revolutionary Self-Defense Organization,” has resumed. The appeal court has also re-opened for the guerrilla organization “Revolutionary Struggle.”

The trial of the anarchist comrade Dimitra Valavani has been postponed. Police violently took her DNA sample through intense intimidation and what has been described as torture, as cited in this statement.

The Road Ahead

We hope that as the lockdown is eased and the seasons change, people do not become forgetful or complacent. We hope that we will remember the woman ticketed for setting a flower at a memorial for students killed at the Polytechnic in Exarchia on November 17, or the memorial flowers for Alexis Grigoropolous that a police officer destroyed on December 6, or the threats of rape and murder that police routinely address to us. We hope that people will remember how, during the lockdown, the police have turned a blind eye to open heroin trafficking and the brothels in which women were forced to work during the pandemic while attacking any expression of dissent. These are among the most egregious examples, but the widespread physical torture and brutality inflicted upon countless students, anarchists, and residents who chose to stand up to the police these last months must not be forgotten.

Many are preparing for this summer as if it is our last meal. We know from these last weeks that all this time, something has been growing—in our hearts and minds, in our courage and commitment. We have grown with many beyond our movements in a society in which COVID-19 has forcibly revealed the true nature of the state and capitalism. In a place where government management is more confusing and Kafkaesque than most places in the world, not even nationalism can blind people to the fact that the current regime has exploited this pandemic.

https://twitter.com/exiledarizona/status/1378684885125230594

As we conclude this month’s report, a new squat has opened in Athens while an autonomous zone in the headquarters of the University of Thessaloniki continues to gain traction with the occupation of the Theater and Science department buildings. At the same time, assaults on refugee communities continue, the COVID-19 death toll is soaring, and police and fascists openly collaborated to attack a squatted social center in Thessaloniki on the 200th anniversary of Greece’s independence from Turkey.

https://twitter.com/exiledarizona/status/1375164308481527816

These last weeks have inspired us, despite all the hurt that inevitably comes with witnessing the atrocities that compel us to resist. Solidarity to those struggling against the state and capitalism everywhere.

Further Reading

We recommend athens.indymedia.org. Abolition media worldwide also consistently posts in English about events in Greece. Act for Free recently had its servers stolen by the Dutch state but is back online here now.

Many face significant charges, financial hardship due to fines amid unemployment, and serious bodily harm resulting from the events described in this report. Fighting repression with solidarity is a long-term process; we invite you to publicize and donate to the fund below as an expression of solidarity.

Ongoing solidarity fund for persecuted and imprisoned revolutionaries in Greece.