It is December 17, 2011. One year ago today, Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in response to his mistreatment by the Tunisian police, setting off a chain reaction worldwide. Let no one forget that the wave of uprisings still sweeping the globe did not simply spring from the hard work of activists, however long some labored to pave the way. It did not begin with people setting out to better themselves or the world. It began with the ultimate gesture of despair and self-destruction.

Bouazizi was not enacting a strategy. He was alone, as alone as a person can be. By drawing back the curtain from injustice so we could come together to fight it, he gave us a precious gift, but a costlier gift than we have any right to receive. The European Parliament awarded him the Sakharov Prize posthumously, but he died knowing only that he had acted on his humiliation and rage, to no end other than to express them. His death hangs in eternity as an irreparable tragedy. We might say the same of so many others who have thrown away their lives in the history of revolutionary struggle.

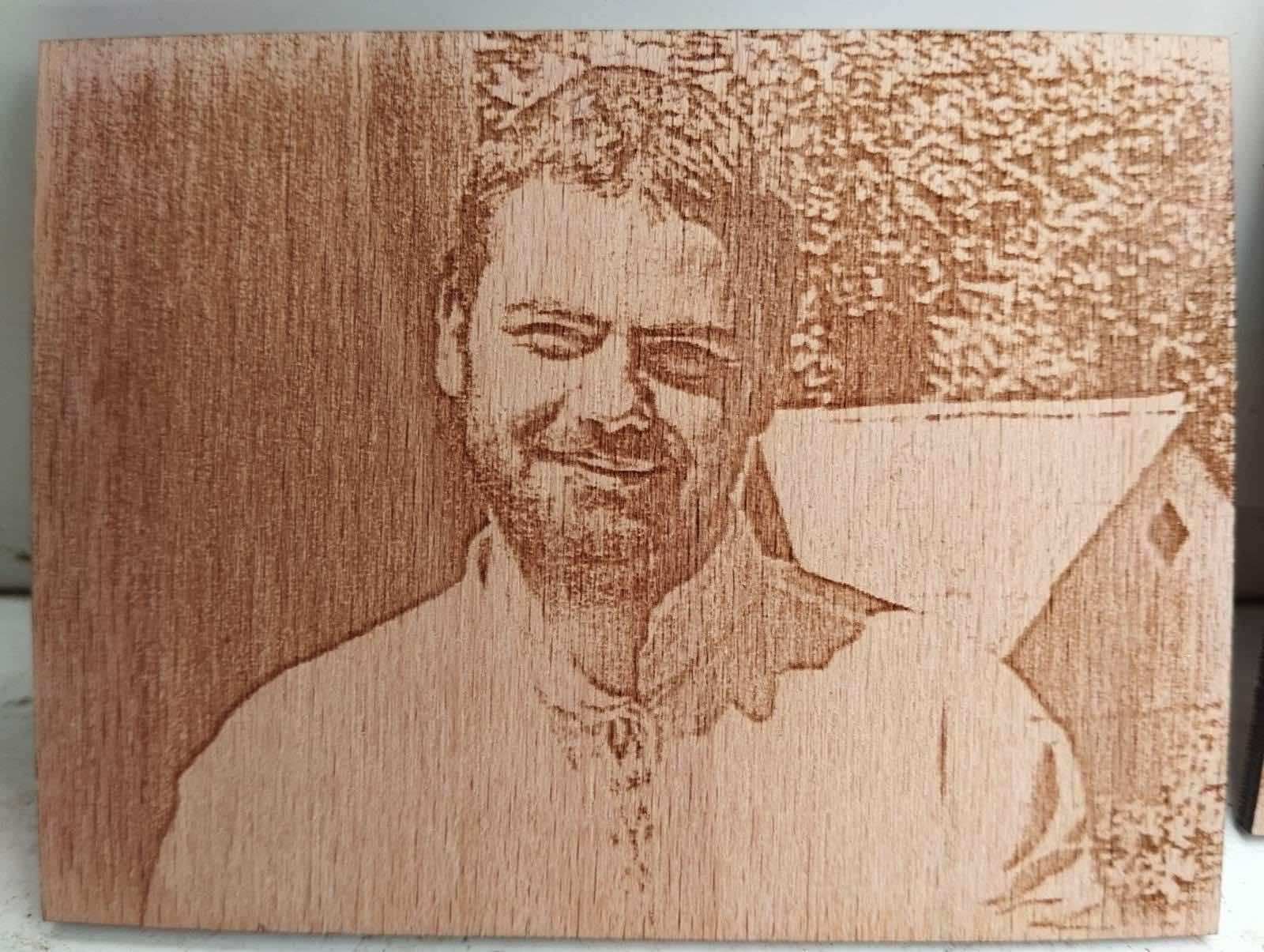

Mohamed Bouazizi.

What can we learn, then, from this man who gave free vegetables to poor families, who had to buy his wares on credit the way many of us must, who reacted against the same policing that imposes inequalities in the US? First, that misery is the same the world over today, even if it assumes different forms. But we can go further: in Bouazizi’s example, we see what it takes to get out of here, even if we do not wish to ignite a worldwide conflagration but simply to change our own lives.

What would life be like after a revolution? The dishwasher pictures a dishroom without a boss. The renter imagines herself in the same little hovel, rent-free. The shopper looks forward to stores without checkout counters. We can hardly imagine beyond this horizon—yet surely it would be easier to change everything entirely than to build a version of this world in which the same institutions and habits magically cease to be oppressive. When what we are is intrinsically determined by capitalism, it’s not enough to try to better ourselves; we have to cease to be ourselves.

In the era of precarity, this is clearer than ever. Globalization has swept the entire population of the planet into one labor pool that competes for the same jobs; mechanization is replacing those jobs, rendering us more and more disposable. In this context, those who set out merely to defend their positions in the economy are doomed. Look at the student movement of 2009-2010, or the protests in Wisconsin last spring: these rearguard struggles to preserve the privileges of a particular demographic could only fail. Today we can neither found our strategy on incremental victories—we are in no more of a position to win them than our rulers are to grant them—nor on the fixed roles that once gave the general strike its force. We have to fight from our shared vulnerability: not on the basis of what we are, but of what we will not be.

The only thing that can bind us in this is our willingness to renounce, to defect, to fight—to abolish the system that created us. This means altering our lives beyond recognition. There are no guarantees in this undertaking; it takes self-destructive abandon. We must not celebrate this, but there is no getting around it.

Dictator Ben Ali visits Mohamed Bouazizi comatose in the hospital, shortly before the latter passed away and the former fled the country

Nothing is more terrifying than departing from what we know. It may take more courage to do this without killing oneself than it does to light oneself on fire. Such courage is easier to find in company; there is so much we can do together that we cannot do as individuals. If he had been able to participate in a powerful social movement, perhaps Bouazizi would never have committed suicide; but paradoxically, for such a thing to be possible, each of us has to take a step analogous to the one he took into the void.

We cannot imagine what Bouazizi went through, nor the hundreds upon hundreds of others who have lost their lives in the struggles throughout North Africa since—only a minute fraction of the casualties of capitalism this past year. Yet in embracing destruction on his own terms, he at least opened a path to something else. When a youngster hoods up for a black bloc or a middle-aged secretary moves into an encampment, departing from all they know, all they have been, they can hope to do the same.

Let’s make our despair into a transformative force. Perhaps we can give a positive meaning to the saying that is so chilling in reference to the gift Mohamed Bouazizi gave us: you have to be ready to die to be ready to live.

“The transformed speaks only to relinquishers. All holders-on are stranglers.” -Rainer Maria Rilke