In this account, participants in the rapid response networks in the Twin Cities describe their experiences, explore the threat represented by the development of Immigration and Customs Enforcement into a political police, and propose a strategy for how the rapid response networks could rise to the challenge and contribute to revolutionary social change.

To learn more about the rapid response chat structure, start here.

All names and locations have been changed to maintain the security of those engaged in rapid response and community defense in the Twin Cities.

We leave the house at 5 am, bundled up in the sub-freezing Minnesota winter. We tread carefully to the car because the ground everywhere is icy. Our driver opens their phone and joins a running Signal call in a 1000-person chat that was created eight hours prior. These neighborhood-based signal chats are re-created daily.

“Hi, this is Patrice signing on, we will be driving for the next couple hours. Our patrol area will be 24th to the south, Main Street to the north, Washington Street to the west, and 5th Avenue to the east.” Its a seven-block area, traversable by car in less than two minutes.

“Good morning, Patrice, that sounds good,” responds one of the dispatchers. Their role is to keep track of where foot and car patrols take place in the southside of Minneapolis and to make sure that all areas are covered. There are 25 other people on the call. Everyone is muted and only unmutes to address the group.

We pull out of the driveway and start our patrol. We hear another voice over the Signal call. “This is Stump, I have a suspicious vehicle headed west on Main at the corner of 7th Avenue. Silver Dodge Ram, Texas plates Alpha Kilo Radio 3863, can I get a plate check?”

“Yep, that’s confirmed ICE,” replies a second dispatcher a few seconds later. Their job is to cross-check license plates with a large data base of plates that have been collected in neighborhoods and at the ICE regional headquarters over the last eight weeks of Operation Metro Surge. The operation began in December.

“We are on 6th Avenue heading north. We will be at the corner of Main in 30 seconds and see if we can catch them,” replies our driver. We approach the intersection and see the Ram speed by. We pull out, careful not to accelerate too quickly and draw attention to ourselves. We follow the truck for three blocks before it pulls into a Burger King parking lot. We keep driving, alerting the others on the call.

Someone responds: “I’m two blocks behind you, I’ll check the Burger King.”

Someone else replies, “I’m on foot a block away, I’ll be there in one minute.”

As we are driving, we see individuals and pairs of people standing at street corners on their phones, with whistles around their necks. People are 3D-printing whistles in massive quantities. We pass cars every few blocks driven by people checking the cross streets, talking into their phones. Following the invasion of 3000 ICE officers, everyday Minnesotans are pouring into rapid response networks and scouring their neighborhoods—even in 20-degree weather before the sun has come up.

“I’m being tailed by a car I think is ICE, I can make out two masked individuals through the tinted windshield,” someone says. The call goes quiet for a few seconds. “I’m being pulled over.”

Dispatch chimes in: “Stay unmuted, turn down your volume so they don’t hear the call, everyone else please stay on mute.” We hear banging, then something shatters. “ICE just smashed their window,” our driver explains calmly, decelerating ahead of a red light. We are shocked, but this is a regular occurrence. Everyone on the call keeps their cool.

We have heard stories from rapid responders about ICE tailing them, boxing them in, smashing their car windows, pepper-spraying them, holding them at gun point, shooting out their tires, detaining them. Some responders have been taken to the regional ICE headquarters, the Whipple building. Others have been driven to the other side of the city and thrown out of the vehicle, alone in the cold. Their cars have been left running in the road. The responders tell us all these stories in passing, quickly returning focus to the work that is to be done.

Of course, ICE has done worse than this, too. ICE agent Jonathan Ross shot and killed Renee Good as she was trying to drive away. A week later, as ICE agents were pursuing someone, they shot live ammunition at a house with a family in it, hitting Julio Sosa-Celis in the leg.

But when you ask patrollers what they want people to know about what’s happening in their city, they barely mention the broken windows and bruises. They describe the feeling of connection and solidarity filling the streets. They make hearts with their hands from car to car, they blow kisses. They make dinners for one another, they drop off groceries for undocumented families that have been locked inside their homes for weeks. They tell us about how, when a skirmish broke out on a busy road, an entire café full of people stood up as one, dropping what they were doing to run towards the sound. We hear again and again about their deep love for the community in the Twin Cities and for their neighbors. Every day, people who never imagined themselves fighting ICE are participating in bold combative actions.

And all of this rings true. Even as guests, volunteers visiting from out of town, we feel like the whole city has our backs.

Later in the day, we head out to get breakfast. We’ve only driven three blocks when we see a group of people running and blowing their whistles. Then we see flashing lights ahead.

We pull over and get out of the vehicle. ICE is leading someone out of their house. Other cars—some driven by people doing rapid response, others just on their way to work—pull over and more people leap out. A few people come running out of their houses, still putting their jackets on. People are screaming at the agents, filming them, throwing snowballs at them.

A neighbor is there, crying. The person ICE detained has two kids in the house, and the neighbor has to go to explain to the kids what just happened to their mom. We try to block the ICE agents, but they quickly get into their vehicles. We jump in our car and follow them. The two cars split up and head in different directions, driving erratically.

The ICE agent we’re tailing is running lights and driving on the wrong side of the street. He almost gets into a head on collision with oncoming traffic. He turns right from the left turn lane, then speeds down a residential street. We lay on the horn behind him.

We came to Minneapolis after the murder of Renee Good because we wanted to understand what was happening in the city and to support the people who were fighting back. We expected to find a city experiencing an ICE surge like the ones that have taken place in Chicago, Los Angeles, Charlotte, or New Orleans.

But the situation in Minneapolis is not like anything we’ve seen before. It’s not just an uptick in raids. It is a full-scale military occupation, confronting you wherever you go. You can’t drive more than a couple blocks without seeing roving bands of cars with tinted windows containing masked men in full military equipment: helmets, balaclavas, long guns, tactical equipment, crowd control munitions. They pull up to bus stops, leap out, grab a brown person, shove them in the car, then speed away. They don’t check papers. Some people have been held in detention centers for weeks before it came out that they were US citizens.

We are witnessing a racial pogrom.

Afterwards, as we are sitting down for breakfast, we get a message that ICE hit someone’s car a few blocks from us. “Abduction in process at the corner of 2nd and Pine. The man is saying he is a US citizen.” We quickly pay and rush to the scene.

In the middle of a block, we see a sedan with its rear end crumpled. Behind it, two ICE vehicles sit with their lights flashing. The agents were pursuing someone and rammed into him, causing an accident in a residential neighborhood. There are cars blocking the intersection on both sides, the occupants standing in the road. Some people are filming, many are whistling and honking their horns, others are yelling at the officers, a few are throwing snowballs. Within 15 minutes, hundreds of people have assembled.

Then ICE reinforcements begin to arrive. They deploy tear gas, pepper spray, and shoot rubber bullets in an attempt to disperse the crowd.

While the rapid response networks haven’t stemmed the flow of abductions, diverting dozens of agents who would otherwise be kidnapping people to engage in crowd control is slowing their operations and demoralizing agents. Gregory Bovino, senior Border Patrol official, recently admitted this, conceding that the ways that community members have responded to ICE operations in the Twin Cities are making his job1 more difficult.

After about an hour of navigating the traffic jam of parked cars and angry residents, the pack of agents succeed in extricating themselves. They release the man who was struck by the ICE vehicle. A senior agent mechanically delivers a few words of apology, but the violence continues throughout the Twin Cities.

At this very moment, ICE is undergoing a transformation into a political police force. Recent leaks show that secret ICE programs seek to exploit every detainee to acquire information, and they aim to deploy up to 2000 “intelligence” assets into communities around the country for the purpose of spying on migrants and citizens alike. These operations—and the strategy of the Department of Homeland Security in general—are not just targeting immigrants; they are also intended to target opponents of the Trump regime.

The administration alleges threats from so-called “Antifa” and the “radical left” to justify their authoritarian consolidation of power. But the fact that the FBI called Renee Good a domestic terrorist and pressured prosecutors to investigate her widow shows what they mean by these terms. The “radical left” is a catch-all term that will be retroactively deployed to describe anyone who is randomly murdered by federal agents—or anyone that they would like to murder. Whenever they say “radical left,” they are saying that they intend to go on murdering people the way that they murdered Renee Good, and they intend to do so with impunity.

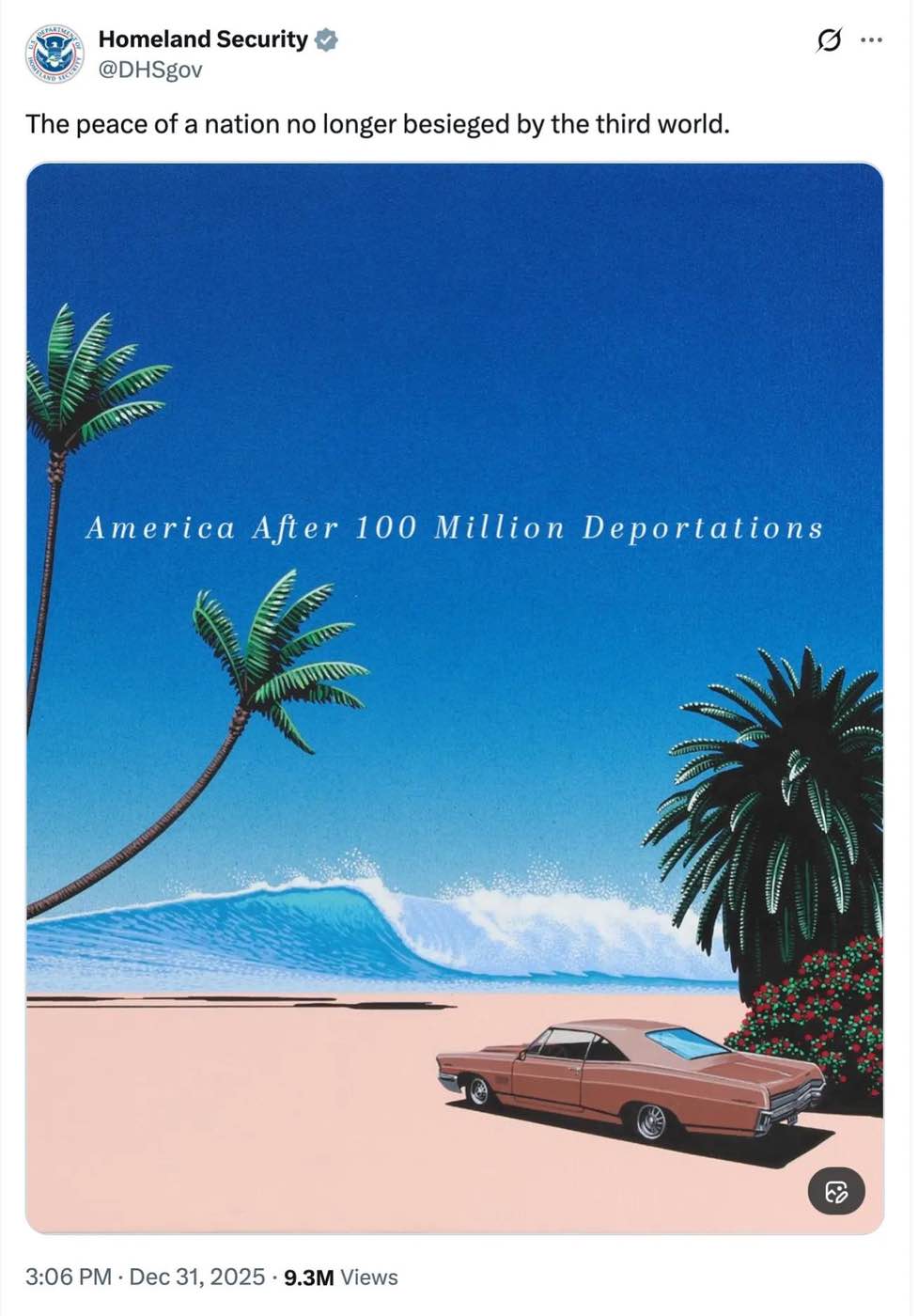

When the Department of Homeland Security posts a meme on its official social media account promoting “100 million deportations,” it should be clear to all that ICE is not just targeting those who currently lack the proper immigration documents. They have all of the hundreds of millions of people who oppose the Trump agenda in their sights. Given a free hand, they will kidnap or murder every single one.

We can catch a glimpse of this in a current federal case in Fort Worth, Texas. Following a July 4th rally at the ICE-operated Prairieland Detention Center in Alvarado, Texas, an officer allegedly sustained a gunshot injury. The officer in question has no medical records substantiating this claim, but the authorities arrested nine people that night and ten more in the months since. All nineteen now face the threat of decades in prison on account of their alleged connection with the rally or else for their political beliefs alone. One Dallas teacher, Dario Sanchez, faces state charges for allegedly removing someone from a Signal group chat. Daniel Sanchez Estrada, a local artist, faces federal charges for carrying a box of pamphlets out of his wife’s home. Neither of these individuals were even at the Prairieland Detention Center for the rally in question.

Whereas the Twin Cities are the front lines of ICE enforcement operations, the Prairieland case shows how they are weaponizing the legal apparatus to crush dissent all around the country. Freedom of speech, freedom of association, and freedom of thought are being disappeared as quickly as our neighbors are. The precedents that they are setting will soon be wielded against anyone who dares to stand up to the rising tide of authoritarianism.

Unless we act fast to stop them.

What You Can Do

If you can, come to Minneapolis. Bring a crew of two or more so you can act independently as you support local organizing. Bring a phone with service and a car with all wheel drive. Plug into local rapid response networks. Don’t rely on a single set of tactics. The situation changes day by day. Be flexible. Be creative. Be bold.

Identify targets that are directly linked to ICE. We need to spread narratives that publicize which companies are complicit in ICE abductions and offer concrete points of intervention. Here are some examples:

- Airports. Every day, deportation flights leave from the Minneapolis-St. Paul Airport to other airports across the country. Yet airport blockades have yet to emerge.

- Hotels. Demonstrations have taken place against Hilton, which houses many of the occupying forces. After a slightly rowdy demonstration, two St. Paul hotels shut their doors completely, displacing the ICE agents in residence. With continued pressure, more franchises and chains might follow suit.

- Car rental companies. Local activists are calling out Enterprise, which has supplied nearly 1000 vehicles to ICE’s unmarked fleet. There are reports that Alamo has similarly rented cars to ICE. With some research, more car companies complicit in ICE snatch-and-grabs will likely emerge.

- Flock. Flock cameras, now well known for their security vulnerabilities and collaboration with ICE, are spreading to cities around the country. Organizers in a number of communities have successfully pressured local governments to remove Flock cameras. Further pressure could continue to erode Flock’s AI surveillance networks.

Expand Rapid Response Networks into Long-Term Political Projects

Unfortunately, in a time of rising authoritarianism, economic crisis, and ecological catastrophe, ICE is not the only danger threatening our communities. What would it take for this movement to become capable of taking the offensive across the country?

- A mouthpiece. In many cities, rapid response networks exist mostly on Signal or Whatsapp. Imagine if the existing networks were able to call for demonstrations, circulate tactical innovations, and coordinate at a regional or national level. If local rapid response networks expanded beyond simply observing and circulating information, they could—for example—call for city-wide general strikes in solidarity with the one taking place in the Twin Cities on January 23.

- An offensive edge. Many existing networks have become very effective at spreading news about ICE attacks and mobilizing responses. The same efficiency and local coordination could be useful for combatting police violence, defending residents against eviction, or providing support to striking workers.

- A revolutionary horizon. Logistically and tactically, rapid response networks are becoming very advanced in terms of communication, counter-surveillance, care, and creativity. Developing a strategic orientation towards revolutionary change, these networks could become a root system from which could emerge a new society, a society that prioritizes the love of humanity over the drive for profit.

Click on the image to download the poster as a printable PDF.

It will not become easier to protest.

It will only become harder to organize.

It is easier to win now that it ever will be again.

We are afraid. We know you are too. But together we can be brave.

We can win.

-

Gregory Bovino was dubbed Border Patrol “Commander at Large” (a rank with no statutory basis) by Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem. The transition from democracy to autocracy involves the emergence of new militarized groups that operate outside the old protocol; Bovino’s “job” reflects this. ↩