Fifteen years ago, we published the following text introducing anarchism to the general public as a total way of being, at once adventurous and accessible. We offered the paper free in any quantity, raising tens of thousands of dollars for printing and even offering to cover the postage to mail copies to anyone who could not afford them. In the first two weeks, we sent out 90,000 copies. It appeared just in time for the “People’s Strike” mobilization against the IMF and World Bank in Washington, DC; the pastor at the Presbyterian church that hosted anticapitalist activists in DC preached her Sunday sermon from the primer as she spoke to her congregation about the demonstrations. Over the following decade, Fighting for Our Lives figured in countless escapades and outreach efforts; read this story for an example. In the end, we distributed 650,000 print copies.

Fighting for Our Lives has been out of print for several years, as we’ve focused on other projects such as To Change Everything. We’ve now prepared a zine version for our downloads library. From this vantage point, we can appreciate both the text and the project itself as ambitious and exuberant attempts to break with the logic of the existing order and to stake everything on establishing new relations. We’ve learned a lot in the years since then—but we haven’t backed down one millimeter.

Read more here.

Overture: A True Story

We dropped out of school, got divorced, broke with our families and ourselves and everything we’d ever known.

We quit our jobs, violated our leases, threw our furniture out on the sidewalk, and hit the road.

We sat on the swings of children’s playgrounds until our toes were frostbitten, admiring the moonlight on the dewy grass, writing poetry on the wind.

We went to bed early and lay awake past dawn recounting all the awful things we’d done to others and they to us—and laughing, blessing and absolving each other and this crazy cosmos.

We stole into museums showing reruns of old Guy Debord films to write faster, my friend, the old world is behind you on the backs of the theater seats.

The scent of gasoline still fresh on our hands, we watched the new sun rise, and spoke in hushed voices about what we should do next, thrilling in the budding consciousness of our own limitless power.

We used stolen calling card numbers to talk our lovers through phone sex from telephone booths in the lobbies of police stations.

We slipped into the offices where our browbeaten friends shuffled papers for petty despots, to draft anti-imperialist manifestos on their computers and sleep under their desks. They were shocked the morning they finally walked in on us, half-naked, brushing our teeth at the water cooler.

We lived through harrowing, exhilarating moments when we did things we had always thought impossible, spitting in the face of all our apprehensions to kiss unapproachable beauties, drop banners from the tops of national monuments, drop out of colleges… and then gritted our teeth, expecting the world to end—but it didn’t!

We stood or knelt in emptying concert halls, on rooftops under lightning storms, on the dead grass of graveyards, and swore with tears in our eyes never to go back again.

We sat at desks in high school detention rooms, against the worn brick of Greyhound bus stations, on disposable synthetic sheets in the emergency treatment wards of unsympathetic hospitals, on the hard benches of penitentiary dining halls, and swore the same thing through clenched teeth, but with no less tenderness.

We communicated with each other through initials carved into boarding school desks, designs spray-painted through stencils onto alley walls, holes kicked in corporate windows televised on the five o’clock news, letters posted with counterfeit stamps or carried across oceans in friends’ packs, secret instructions coded into emails from anonymous accounts, clandestine meetings in coffee shops, love poetry carved into the planks of prison bunks.

We sheltered illegal immigrants, political refugees, fugitives from justice, and adolescent runaways in our modest homes and beds, as they too sheltered us.

We improvised recipes to bake each other cookies, cakes, breakfasts in bed, weekly free meals in the park, great feasts celebrating our courage and kinship so we might taste their sweetness on our very tongues.

We entrusted each other with our hearts and appetites, together composing symphonies of caresses and pleasure, making love a verb in a language of exaltation.

We wreaked havoc upon their gender norms and ethnic stereotypes and cultural expectations, showing with our bodies and our relationships and our desires just how arbitrary their supposed laws of nature were.

We wrote our own music and performed it for each other, so when we hummed to ourselves we could celebrate our companions’ creativity rather than repeat the radio’s dull drone.

In borrowed attic rooms, we tended ailing foreign lovers and struggled to write the lines that could ignite the fires dormant in the multitudes around us.

In the last moment before dawn, flashlights tight in our shaking hands, we dismantled the power boxes on the buildings where fascists were to host rallies the following day.

We fought those fascists tooth, nail, and knife in the streets, when no one else would even confront them in print.

We planted gardens in abandoned lots, hitchhiked across continents in record time, tossed pies in the faces of kings and bankers.

We played saxophones together in the darkness of echoing caves in West Virginia.

In Paris, armed with cobblestones and parasols, we held the gendarmes at bay for nights on end, until we could almost taste the new world coming through the tear gas.

We fought our way through their lines to the opera house and took it over, and held discussions there twenty-four hours a day as to what that new world should be.

In Chicago, we helped create an underground network to provide illegal abortions in safe conditions and a supportive atmosphere, when the religious fanatics would have preferred us to die in shame and tears down dark alleys.

In New York, we held hands and massaged each other’s shoulders as our enemies closed in to arrest us.

In Quebec, we tore up the highway and pounded out primordial rhythms on the traffic signs with the fragments, and the sound was vaster and more beautiful than any song ever performed in a concert hall.

In Santiago, we robbed banks to fund papers of transgressive poetry.

In Siberia, we plotted impossible escapes—and carried them out, circumnavigating the globe with forged papers and borrowed money to return to the arms of our friends.

In Montevideo, in the squatted township, we built huts from plywood and plastic sheeting, pirated electricity from nearby power lines, and conferred with our neighbors as to how we could contribute to our new community.

In San Diego, when they jailed us for speaking our minds, we invited our friends and filled their prisons until they had to change their policies.

In Oregon, we climbed trees and lived in them for months to protect the forests we had hiked and camped in as children.

In Mexico, when we met hopping freight trains, we traded stories about working with the Zapatistas in Chiapas, about floods witnessed from boxcars passing through Texas, about our grandparents who fought in the Mexican revolution.

We fought in that revolution, and the Spanish civil war, and the French resistance, and even the Russian revolution—though not for the Bolsheviks or the Tsar.

Sleepless and weather-beaten, we crossed the Ukraine on horseback to deliver news of the conflicts that offered us another chance to fight for our freedom.

Tense but untrembling, we smuggled posters, books, firearms, fugitives, ourselves across borders from Canada to Pakistan.

We lied with clean consciences to homicide detectives in Reno and military police in Santos.

We told the truth to each other, even truths no one had ever dared tell before.

When we couldn’t overthrow governments, we raised new generations who would taste the sweet adrenaline of barricades and wheatpaste, who would carry on our quixotic quest when we fell or fled before the ruthless onslaught of the servile and craven.

When we could overthrow governments, we did.

We stood behind the witness stand, one after another, decade after decade, century after century, and shouted so the deafest self-satisfied upright citizen at the back of the courtroom could hear it: “… and if I could do it all over again, I would!”

As the sun rose after winter parties in unheated squats, we gathered up great sacks of broken glass and washed stacks of dirty dishes in freezing water, while our critics, sequestered in penthouses with maid service, demanded to know who would take out the garbage in our so-called utopia.

When the good intentions of liberals and reformists broke down in bureaucracy, we collected food from the trash to feed the hungry, broke into condemned buildings and transformed them into palaces fit for pauper kings and bandit queens, held the sick and dying tight in our loving arms.

We fell in love in the wreckage, shouted out songs in the uproar, danced joyfully in the heaviest shackles they could forge; we smuggled our stories through the gauntlets of silence, starvation, and subjugation, to bring them back to life again and again as bombs and beating hearts; we built castles in the sky from the ruins of hell on earth.

One of us even assassinated the President of the United States.

Accepting no constraints from without, we countenanced none within ourselves, either, and found that the world opened before us like the petals of a rose.

I’m speaking, of course, of anarchists—and when people ask me about my politics, I tell them: the best reason to be a revolutionary is that it is simply a better way to live. Their laws guarantee us the right to remain silent, the right to a public trial by a jury of our peers (though my peers wouldn’t put me on trial—would yours?)—what about the right to live life like we won’t get another chance, to have reasons to stay up all night in urgent conversation, to look back on every day without regret or bitterness? Such rights we can only claim for ourselves—and shouldn’t these be our central concerns, not the minutiae of protocol and survival?

For those of us born into a captivity gilded by the blood and sweat of less fortunate captives, the challenge of leading a life worth living of stories worth telling is a lifelong project, and a formidable one; but all it takes, at any moment, to meet this challenge is to contest that captivity.

When we fight, we’re fighting for our lives.

It’s true. If your idea of healthy human relations is a dinner with friends at which everyone enjoys everyone else’s company, responsibilities are divided up voluntarily and informally, and no one gives orders or sells anything, then you are an anarchist, plain and simple. The only question that remains is how you can arrange for more of your interactions to resemble that model.

Whenever you act without waiting for instructions or official permission, you are an anarchist. Any time you bypass a ridiculous regulation when no one’s looking, you are an anarchist. If you don’t trust the government, the school system, Hollywood, or the management to know better than you when it comes to things that affect your life, that’s anarchism, too. And you are especially an anarchist when you come up with your own ideas and initiatives and solutions.

As you can see, it’s anarchism that keeps things working and life interesting. If we waited for authorities and specialists and technicians to take care of everything, we would not only be in a world of trouble, but dreadfully bored—and boring—to boot. Today we live in that world of (dreadfully boring!) trouble precisely to the extent that we abdicate responsibility and control.

Anarchism is naturally present in every healthy human being. It isn’t necessarily about throwing bombs or wearing black masks, though you may have seen that on television. (Do you believe everything you see on television? That’s not anarchist!) The root of anarchism is the simple impulse to do it yourself: everything else follows from this.

Does Anarchy Work?

People with very little actual historical background often say of anarchy that it would never work—without realizing that not only has it worked for much of the history of the human race, but it is in fact working right now. For the time being, let’s set aside the Paris Commune, Republican Spain, Woodstock, open-source computer programming, and all the other famed instances of successful revolutionary anarchism. Anarchy is simply cooperative self-determination—it is a part of everyday life, not something that will only happen “after the revolution.” Anarchy works today for circles of friends everywhere—so how can we make more of our economic relations anarchist? Anarchy is in action when people cooperate on a camping trip or to arrange free meals for hungry people—so how can we apply those lessons to our interactions at school, at work, in our neighborhoods?

To consult chaos theory: anarchy is chaos, and chaos is order. Any naturally ordered system—a rainforest, a friendly neighborhood—is a harmony in which balance perpetuates itself through chaos and chance. Systematic disorder, on the other hand—the discipline of the high school classroom, the sterile rows of genetically modified corn defended from weeds and insects—can only be maintained by ever-escalating exertions of force. Some, thinking disorder is simply the absence of any system, confuse it with anarchy. But disorder is the most ruthless system of all: disorder and conflict, unresolved, quickly systematize themselves, stacking up hierarchies according to their own pitiless demands—selfishness, heartlessness, lust for domination. Disorder in its most developed form is capitalism: the war of each against all, rule or be ruled, sell or be sold, from the soil to the sky.

We live in a particularly violent and hierarchical time. The maniacs who think they benefit from this hierarchy tell us that the violence would be worse without it, not comprehending that hierarchy itself, whether it takes the form of inequalities in economic status or political power, is the consequence and expression of violence. Not to say that forcibly removing the authorities would immediately end the waves of violence created by the greater violence their existence implies; but until we are all free to learn how to get along with each other for our own sake, rather than under the guns directed by the ones who benefit from our strife, there will be no true peace between us.

This state of affairs is maintained by more than guns, more than the vertigo of hierarchy, of kill-or-be-killed reasoning: it is also maintained by the myth of success. Official history presents our past as the history of Great Men, and all other lives as mere effects of their causes; there are only a few subjects of history, they would make us believe—the rest of us are its objects. The implication is that there is only one truly free man in all society: the king (or president, executive, movie star…). Since this is the way it has always been and always will be, the account goes, we should all fight to become him, or at least accept our station beneath him gracefully, grateful for others beneath us to trample when we need reassurance of our own worth.

But even the president isn’t free to go for a walk in the neighborhood of his choosing. Why settle for a fragment of the world, or less? In the absence of force—in the egalitarian beds of true lovers, in the democracy of devoted friendships, in the topless federations of playmates enjoying good parties and neighbors chatting at sewing circles—we are all queens and kings. Whether or not anarchy can “work” outside such sanctuaries, it is becoming clearer and clearer that hierarchy doesn’t. Visit the model cities of the new world order—sit in a traffic jam of privately owned vehicles, among motorists sweating and swearing in isolated unison, an ocean filling with pollution to your right and a ghetto on your left where uniformed gangs clash with ununiformed ones—and behold the apex of human progress. If this is order, why not try chaos!

Anarchy, not Anarchism!

To say that anarchists subscribe to anarchism is like saying pianists subscribe to pianism. There is no Anarchism—but there is anarchy, or rather, there are anarchies.

For as long as power has existed, the spirit of anarchy has been with us too, named or nameless, uniting millions or steeling the resolve of a single one. The slaves and savages who fought the Romans for their freedom and lived in armed liberty, equality, and fraternity, the mothers who raised their daughters to love their bodies in defiance of the diet advertisements leering from all sides, the renegades who painted their faces and threw tea into Boston Harbor, and all the others who took matters into their own hands: they were anarchists, whether they called themselves Ranters, Taborites, Communards, Abolitionists, Yippies, Syndicalists, Quakers, Mothers of the Disappeared, Food Not Bombs, Libertarians, or even Republicans—just as we are all anarchists, to the extent that we do the same. There are as many anarchists today as there are students cutting class, parents cheating on their taxes, women teaching themselves bicycle repair, lovers desiring outside the lines. They don’t need to vote for an anarchist party or party line—that would disqualify them, at least for that moment—to be anarchists: anarchy is a mode of being, a manner of responding to conditions and relating to others, a class of human behavior… and not the “working” class!

Forget about the history of anarchism as an idea—forget the bearded guys. It’s one thing to develop a language for describing a thing—it’s another thing entirely to live it. This is not about theories or formulas, heroes or biographies—it’s about your life. Anarchy is what matters, everywhere it appears, not armchair anarchism, the specialists’ study of freedom! There are self-proclaimed anarchists who never experienced a day of anarchy in their lives—we should know how much to trust them on the subject!

So how will the anarchist utopia work? That’s a question we’ll never again be duped into disputing over, a red herring if there ever was one! This isn’t a utopian vision, or a program or ideal to serve; it’s simply a way of proceeding, of approaching relationships, of dealing with problems now—for surely we’ll never be entirely through dealing with problems! Being an anarchist doesn’t mean believing anarchy, let alone anarchism, can fix everything—it just means acknowledging it’s up to us to work things out, that no one and nothing else can do this for us: admitting that, like it or not, our lives are in our hands—and in each others’.

Is This What Democracy Looks Like?

Anarchists might use democratic methods—but we don’t let democracy use us. For us, the first and last matter is always the needs and feelings of the individuals involved—any system to address them is provisional at best. We don’t try to force ourselves into the confines of any established procedures—we apply procedures to the extent that they serve human needs, and discard them past that point. Seriously, what should come first—our systems, or us?

We cooperate or coexist with others, including other life forms, whenever it’s possible. But we don’t prize consensus, let alone The Rule of Law, above our own values and dreams—when we can’t come to an agreement, we go our own ways rather than limiting each other. In extreme cases, when others refuse to acknowledge our needs or persist in doing unconscionable, harmful things, we intercede by whatever means are necessary—not on behalf of Justice or revenge, but simply to represent our own interests.

We see laws as nothing more than the shadows of our predecessors’ customs, lengthened by the years to seem wiser than our own judgment. They persist as undead creatures, imposing unnatural stipulations upon us that do not enable justice, but only interfere with it—while at the same time estranging us from it, framing it as something we cannot carry out without arcane formalities and judges’ wigs. These laws, having multiplied and calcified over time, are now so alien and inscrutable that a priest class of lawyers makes a living off the rest of us as astrologers of the stars our well-meaning ancestors set in precarious orbit. The man who insists that justice can only be maintained by the rule of law is the same one who appears on the witness stand at the war crime tribunal swearing he was only following orders. There’s no Justice—it’s just us.

The Economics of Anarchy

Anarchist economies are radically different from other economies. Anarchists not only conduct their transactions differently, but trade in an entirely different currency—a currency that is not convertible into the kind of assets for which capitalists compete and communists draft Five Year Plans. Capitalists, socialists, communists exchange products; anarchists interchange assistance, inspiration, loyalty. Capitalist, socialist, communist economies make human interactions into commodities: policing, medical care, education, even sexual relations become services that are bought and sold. Anarchist economies, focusing above all on the needs and desires of the individuals involved, transform products back into social relations: the communal experience of gardening or gathering berries or playing music, the excitement of looting a supermarket or occupying a building. The typical economic interaction in capitalist relations is the sale; in anarchist economics, it is the gift.

Anarchist economies depend on commons, which are the opposite of private property. Private capital disappears when utilized, as in the case of money spent by day laborers on food—or, when enough of it accrues, it serves to accrue more private capital at others’ expense, as in the case of the corporation that exploits those laborers. Commons, on the other hand, are available in abundance, and the more they are utilized, the more abundant they become: the community garden that produces more food the more people cooperate in it, the squatted building that is better renovated for community usage and better defended from the police the more people commit to it. In friendships, as in lovemaking, as in potluck dinners and dancing, the more one gives, the more everyone gets.

Today, most of us participate in both kinds of economies at once. Ostensibly private property is still shared, at least in limited contexts: a teenager brings his basketball for the neighborhood game, a rock band buys a communal van. Even a house belonging to a middle class family, although off-limits for most, still hosts visiting relatives, a PTA meeting, a sleep-over party. Instances like these are reminders of how much more pleasurable sharing can be than commerce. Anarchists nurture visions of a world suitable for a sharing that knows no borders.

But Who Will Take out the Garbage?

It was in Barcelona, some years after the civil war, when the memory of the syndicates still remained, unutterable, under the iron heel of the fascist regime.

City bus #68 was making its rounds one particularly sunny spring day, when the driver slammed on the brakes at an intersection. “Fuck this,” he swore in angry Catalan, and, opening the bus doors, stomped out into the sunshine.

The passengers watched in shock at first, and then began to protest anxiously. One of them stood up and started to honk the horn. After a few tentative beeps, he leaned on it with all his might, sounding it like a burglar alarm; but the fed up ex-bus driver continued, nonchalant, on his way down the street.

For a full minute, the riders sat in stupefied silence. A couple stood up and got off the bus themselves. Then, from the back of the bus, a woman with the appearance of a huge cannon ball and an air of unconquerable self-possession stepped forward. Without a word, she sat down in the driver’s seat, and put the engine in gear. The bus continued on its route, stopping at its customary stops, until the woman arrived at her own and got off. Another passenger took her place for a stretch, stopping at every bus stop, and then another, and another, and so #68 continued, until the end of the line.

It means figuring out how to work together to meet our individual needs, working with each other rather than “for” or against each other; and when this is impossible, it means preferring strife to submission and domination.

It means not valuing any system or ideology above the people it purports to serve, not valuing anything theoretical above the real things in this world. It means being faithful to real human beings (and animals, and ecosystems), fighting for ourselves and beside each other, not out of “responsibility,” not for “causes” or other intangible concepts. It means denying that there is any universal standard of truth, aesthetics, or morality, and contesting wherever it appears the doctrine that life is essentially one-dimensional.

It means not forcing your desires and experiences into a hierarchical order, but acknowledging and embracing all of them, accepting yourself. It means not trying to compel the self to abide by any external laws, not trying to restrict your emotions to the sensible or the practical or the “political,” not pushing your instincts and passions into boxes: for there is no cage large enough to accommodate the human soul in all its flights, all its heights and depths. It means seeking a way of life which gives free play to all your conflicting inclinations in the process of continuously challenging and transforming them.

It means not privileging any one moment of life over the others—not languishing in nostalgia for the good old days, or waiting for tomorrow (or, for that matter, for “the” Revolution!) for real life to begin, but seizing and creating it in every instant. Yes, of course it means treasuring memories and planning for the future—it also means remembering there is no time happiness, resistance, life ever happens but NOW, NOW, NOW!

It means refusing to put the responsibility for your life in anyone else’s hands, whether that be parents, lovers, employers, or society itself. It means taking the pursuit of meaning and joy in your life upon your own shoulders.

Above all! It means not accepting this or any manifesto or definition as it is, but making and remaking it for yourself.

Civic Hedonism

What’s good for others is good for us, since our relationships with them make up the world in which we live; but serving their needs at our own expense would cheat them of our potential as free and happy companions, which is perhaps the best gift we can offer. Our vision of healthy relationships rests on the notion that self versus other, selfish versus selfless, is a false dichotomy, like all dichotomies. Those who preach self-sacrifice for the greater good are still working from the competitive model of individual-versus-society, as are those who would aspire to an individualist independence; for us, individuals and communities alike are both convergences of threads in the great web of existence, inseparable from one another, corresponding to one another. The freedom and self-determination we cherish are only possible in the context of the culture we create together; yet in order to contribute to that creation, we must create ourselves individually.

That is: if you can save yourself, you could save the world—but you must save the world to save yourself.

A Fellowship of Friends and Lovers

As anarchists propose that friendship, or at least family ties, could be the model for all relationships, we prize above all those qualities which make good friendships possible: reliability, generosity, gentleness. Most of us have been indoctrinated into hierarchy and contention since we were born, and that makes it no small feat to interact in ways that liberate and enable more than cripple—still, it happens all the time! Each of us tries to give without demanding in return, to be a person with whom no one must feel ashamed. It’s been said that we are against marriage, but the opposite is true: yes, we emphasize that no one is the property of another, but even more so that everybody on this planet is already permanently intertwined—and we insist that everyone act accordingly.

All this is not to say we approach soldiers with flowers when they come for our children—nor do we offer corporations our children when they come for our flowers. Sometimes love can only speak through the barrel of a gun.

Self-Determination Begins at Home

Not to be forced by expectation, doctrine, or necessity to claim one fragment of yourself and disown others. Not to take sides within and against yourself, not to play judge and jury constantly at your own trial. Not to protect pristine ignorance with inaction, but to learn from mistakes and thus grow wise. Not to choose one path in life and follow it to the exclusion of all others, but to throw false unity and consistency to the wind—to give expression to every impulse and yearning in what you deem its proper time, and appreciate what is fertile in turmoil. To do this knowing you are a part of a community that cherishes you unconditionally—and to cherish others in their entirety, as they reflect parts of yourself.

To live without the petty squabbles of pecking order and power structure inside any more than around—that is the anarchist dream of selfhood.

Direct Action Gets the Goods

A community in which people direct their own activities and look out for each other does not need a prison or factory built in it to “create jobs.” A community of people who share their own channels of communication are not at the mercy of any corporate media version of “truth.” A community of people who make their own music and art and organize their own social events would never settle for the paralyzing spectacle of reality television, let alone computer dating services and pornography. A community of people who know each other’s histories and understand each other’s needs can work through conflicts without any need for interference from uniformed strangers with guns. The extent to which we can create these communities is the extent to which we can solve the problems we face today, and no legislation or charity will do this for us.

Institutions can only be as good as the people who make them work—and they usually aren’t, anyhow. Solutions “from above” have proved ineffective over and over: the red tape of medical programs, the inefficiency of social services, the lies of presidents. If you don’t trust the people, you can be sure you can’t trust the police.

All Gods, All Masters

Anarchism is aristocratic—anarchists just insist that the elite should consist of everyone, that the struggle of the “common man” can become the struggle of the uncommon women and men it produces.

We have no illusions that there are any shortcuts to anarchy. We don’t seek to lead “the” people, but to establish a nation of sovereigns; we don’t seek to be a vanguard of theorists, but to empower a readership of authors; we don’t seek to be the artists of a new avant garde, but to enable an audience of performers—we don’t so much seek to destroy power as to make it freely available in abundance: we want to be masters without slaves.

We recognize that power struggles and dynamics will always be a part of human life; many of us have a “tyrannical muse” we obey, albeit willingly, so we reserve even the right to command and serve when it pleases us. But, as they say, the only free human beings are the pauper and the king—the king being the less free of the two, since his kingdom still encumbers and limits him, while on her luckier days the hobo can feel that the whole of the cosmos exists for the sake of her pleasure and freedom—so we prefer not to trivialize ourselves by competing for such fool’s gold as ownership or authority. And—when struggle is unavoidable, we would still prefer to be at the mercy of the violence and stupidity of other individuals than the violence and stupidity of humanity as it is distilled and marshaled by the state.

We’re not egalitarians in the old sense: we’re not out to pull the rich and powerful down to “our level”—rather, we pity them for not being ambitious enough in their aspirations, and hope they will abdicate to join us in fighting to make it possible for everyone to ascend to greatness (that way, we won’t have to guillotine them). We’re not against the glory assigned to pop icons and movie stars, per se—we just deplore the way it is squandered on distant objects, when it rightfully belongs to the moments of our own heroic lives. We’re not against the homage and devotion that the monototheists’ God receives; we simply find it healthier to devote it to each other. We’re not against property, exactly, so much as we are the pettiness of bickering over it: for we understand that to rule the world, we must share it all—and not demolish or meddle with it, for that matter. The true pauper king walks the forests of his domain proudly, watching the interactions of the complex ecosystems in awe, knowing the only appropriate conduct for a monarch of such a wonderland is a policy of veneration and non-intervention (except to thwart the occasional logging corporation). We’re not waiting for “the” revolution to give us the rights we deserve; deeming ourselves the highest authorities we need recognize, we grant them to ourselves immediately and therefore make revolution constantly as a way to assert and protect them.

We will settle for nothing less than total world domination, for one and all.

…And Every God an Atheist

Anarchists not only deny the authority of God, Chief of Police of the Universe, but also maintain a healthy distrust of his successors: Nature, History, Science, Morality. We don’t account any being, system, or tradition the right to our unquestioning faith, since even when we esteem others’ knowledge or judgment better than our own we are still responsible for the choice to trust them. Accordingly, we don’t regard any contention or assumption as above dispute, and revel more in moving freely between paradigms than in debating which one is The Truth. We are especially suspicious of experts who would mediate between us and deities or spheres of knowledge, and prefer both to learn about the world and to contact the divine for ourselves.

Justice as Judgment we count of little worth: we want to be practical, to solve problems, not to treat human relations and conduct as another economic exchange with righteousness for currency. We apply the idea of personal responsibility only to the extent that it is useful in making our relationships work; otherwise, it is of little interest to us whether a person’s soul is damned or redeemed, whether conduct is moral or immoral, whether society or the individual is to blame for a wrong.

Let it not be said about us that we hold nothing holy! On the contrary, we hold everything holy. Denying hierarchy means venerating the singular, incomparable beauty of every creature, every feature of the cosmos, every moment. Only appraisal and condemnation are anathema to us.

Graffiti on a church in Lisbon, 2001: “Without truth, you are the looser.”

“The anarchist is a very fierce creature. It is first cousin to the gorilla. It kills presidents, princes, executives, likewise sabotages their summits and summer holidays. It has long, unkempt hair on its head and all over its face. Instead of fingernails it has long, sharp claws. The anarchist has many pockets in which it carries rocks, knives, guns, and bombs. It is a night animal. After dark, it gathers in groups, large and small, and plans raids, murders, plagues. Lots are drawn to select who must carry out the work.

“The anarchist does not like water. It never washes or changes its clothes. It is always thirsty and drinks only salt water. The home of the anarchist is in Europe, especially Italy. Some few have been exported to North America, where they are feared and hated by all decent folks and hunted wherever they show themselves.

“Papa does not like anarchists a bit. They give him bad dreams, he says. He has given orders to have them caught and put in cages, and he will not allow any more to come into this country if he can help it. If any sneak in, he will have them shot like rabid dogs, Mexicans, mountain lions, and such animals. I practice every day with my rifle so I can shoot these wild beasts when I grow up.”

-A White House nursery composition, 1904

Against Gross Generalizations

All of us have grown up divided and conquered along lines of gender and sexual preference, body type and ethnicity, class and race, bought off with privileges and beaten down with psychological warfare so we’ll do our parts to keep the pecking order in place. White supremacy, patriarchy, and heterosexism are the pillars of this civilization. We anarchists fight against these oppressive structures whether we find them in society or ourselves; but we aim for more than the liberation of human beings of all identities—we want the liberation of all human beings from identity.

There are no universals. Group identities are self-perpetuating fabrications that begin with circumstantial evidence and end by imposing a false uniformity. There are two genders, for example, like there are “only” twelve tones in every octave: it seems true when you look at a piano, but try opening your mouth and singing! Though “femininity” may appear ordained by nature to those who grew up in environments where all women shave their legs and armpits, it is just a generalization drawn from generations of standardized behavior, reinforced by each replication. But—as there is no “pure” femininity, no substance the generalization refers to besides what all the individual instances are perceived to have in common, and so each generation is not the “original” but a “copy”—the entire paradigm is at risk in every new generation, as it may be transformed…or abandoned.

At best, generalizations like class and gender can be used to undo themselves—to expose and confront the patterns of oppression that run through individual lives, to find common cause in fighting the invisibility of certain experiences and histories. We want to get beyond these and all categories and conflicts, but it’s only going to happen if we begin by addressing them. In men’s groups, human beings constructed as men can exchange skills for rewiring their programming; in women-only spaces, those constructed as women can explore similarly without the presence of men interfering. We defend the right of individuals to choose how they want to be identified—and no vision of unbounded life is any excuse to pretend the world is yet free anywhere from power imbalances. But ultimately it is revolution we’re after, not reform: we’re not petitioning for more rights for special interest groups, or more freedom of movement between established categories—we’re taking and making our right to make and remake ourselves in every moment, and wrecking the system of divisions in the process!

We are feminists who would abolish gender, labor organizers who would abolish work, artists fighting to destroy and transcend art. Our class war is a war against class, against classes and classification. When we say that we are against representation, we do not only mean representative “democracy”; we also mean that each of us is an irreducible individual, that none can speak for another. Neither politicians nor abstractions, neither delegates nor demographics can represent us!

Anarchists Make Revolutions, not War

Beware of struggle. Not a few radicals get involved in politics because they know everything about resisting and little about anything else. They turn every interaction into a conflict between the forces of good and evil, taking a stand and drawing the line until it really is them against the world. For would-be career agitators, this can be a great way to maintain that career—but it accomplishes little else beyond getting people agitated in the strictest sense of the word. Most will just stop paying attention entirely—who doesn’t already have enough antagonism and unpleasantness to deal with?

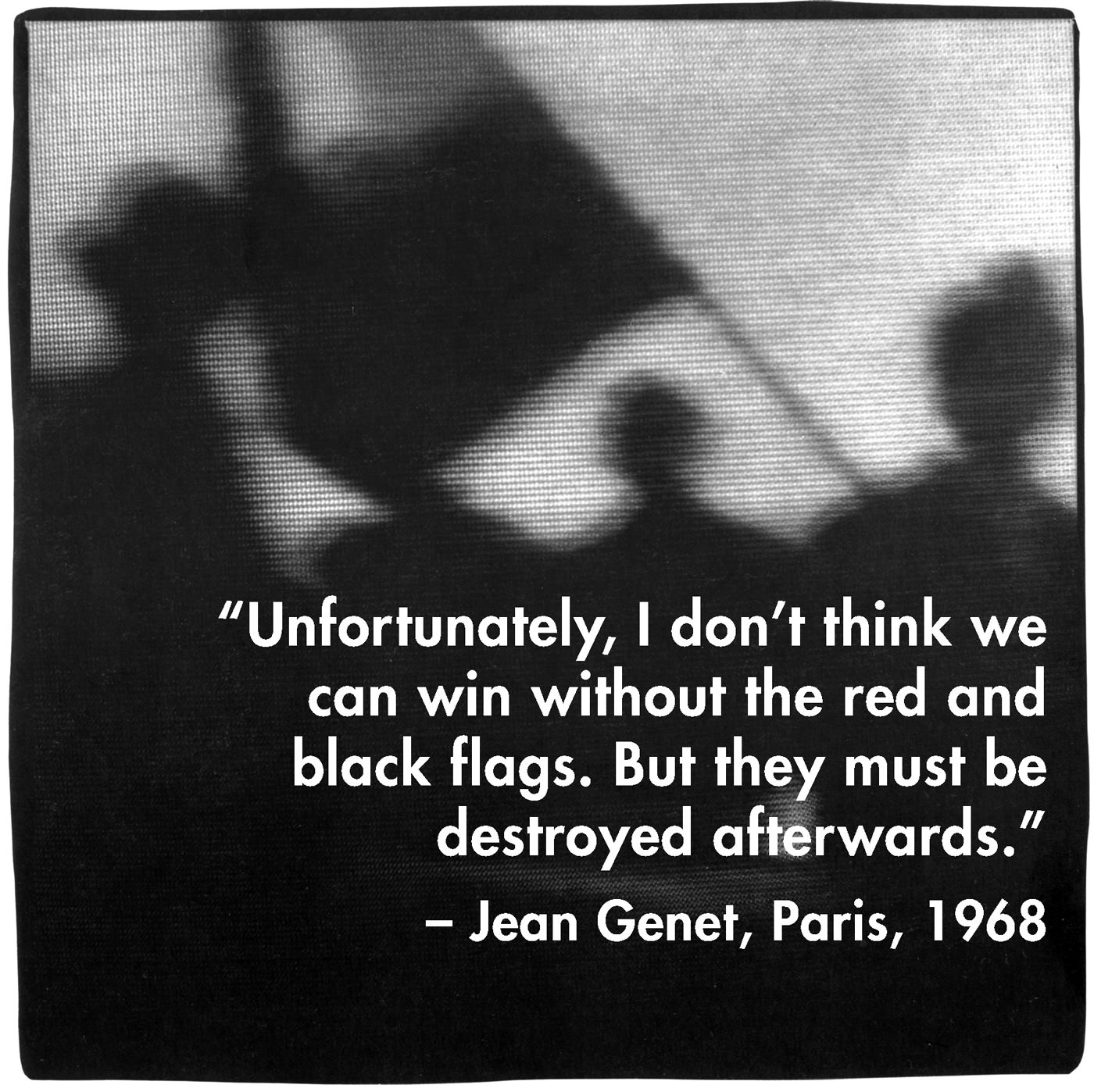

There are always wars waiting to be fought—against, against, against. Fighting these wars perpetuates the dualities that give rise to them. Anarchists anachronize wars, by transcending oppositions. That is revolution.

Don’t join an existing conflict on its terms and make yourself a pawn of its patterns: redefine the terms of the conflict—from “democracy versus terrorism” to “freedom versus power,” for example! Find ways to make premises subvert themselves, to draw people together in ways they thought impossible, to upset the entire paradigm of struggle.

Not a Position, but a Proposition

So if you want to provoke revolt, don’t draw a line between yourself and the rest of the world and threaten everyone across it. Don’t propagate a universal program, don’t campaign for recruits, for heaven’s sake don’t “educate the masses”! Forget about persuading people to your opinion—encourage them to develop the power to form their own. Everyone having their own ideas is more anarchist than everyone having The Anarchist Idea. Any central organization or recognized authority on revolt can only stifle self-determination by ordering it. Individuals acting freely, on the other hand, can inspire and reinforce liberty and resistance in each other: independence, like all good things, is available in abundance. It certainly doesn’t need to be—cannot be—doled out sparingly by a central committee to constituents waiting in breadlines!

When it comes to addressing others, don’t try to say “the” truth. Meddle with The Truth, undermine it, create a space in which new truths can form. Introduce questions, not answers—and remember, not all questions end in question marks. For the revolutionary, the essence of a statement lies in its effects, not in whether or not it is “objectively” true—this approach distinguishes her from philosophers and other idle bastards.

Historians tell of the mighty emperor Darius, who led his troops into the steppes with the intention of subduing the Scythians and adding their territory to his empire. The Scythians were a nomadic people, and when they learned that Darius’ forces were to descend upon them, they broke camp and began a slow retreat. They moved at such a speed that though Darius’ armies could always descry them on the horizon, they were never able to close in. For days they fled ahead of the invaders—then weeks, months, leaving all the food in their wake destroyed and all the water poisoned; they led the intruding armies in circles, into the lands of neighboring peoples who attacked them, through unbroken deserts where gaunt vultures licked bleached bones. The proud warriors, accustomed to flaunting their bravado in swift, dramatic clashes, were in despair. Darius sent a message with his fastest courier, who was barely able to deliver it to the laziest straggler of the Scythian flank: “As your ruler,” it read, “I order you to turn and fight!”

“If you are our ruler,” came the reply, scratched carelessly into a rock face they came upon the next day, “go weep.”

Days later, after they had given up all hope, the scouts made out a line of Scythian horsemen charging forward across the plain. They were waving their swords excitedly and letting out great whoops of enthusiasm. Caught unprepared but relieved at the prospect of doing battle at last, the warriors took up their arms—only to discern, in confusion, that the Scythians were not charging their lines, but somewhat to the side of them. Looking closer, they made out that the horsemen were pursuing a rabbit. Upon this humiliation, the soldiers threatened mutiny, and Darius was forced to turn back and leave Scythia in defeat. Thus the Scythians entered history as the most unconquerable of clans by refusing to do battle.

Anarchism Is a Paradox

…but it’s the kind of paradox we anarchists relish. Urging people to think for themselves, seizing power to abolish it, making war on war, these are all contradictions—but it’s good tactics to engage in obvious hypocrisy, if you want the rebels to depose you along with other authorities! Flying a black flag to express opposition to flags sounds senseless—but, living in the shadow of so many flags that flaglessness is interpreted as acquiescence, it may be sound senselessness. Better a black flag than a white one, anyway!

Create Momentum!

So—Create momentum! Don’t sit endlessly in meetings, meeting about when you should be meeting to discuss how to conduct your next meeting. If your masochistic comrades feel the unfathomable compulsion to spend weeks, months, years of yammering hammering out the wording of a platform to which they can all pledge themselves, and then further years in internal dissension and rupturing, let them, but don’t feel obliged to join in just to prove how committed to the Revolution you are. Don’t feel obliged to join in anything—this is your revolution!

Create momentum! Don’t demand change—realize it yourself with your actions. All you can accomplish is what you do yourself with your companions, and that’s a lot: this is how you keep your dignity in a mad world, how you write your own life story and thus let others know they aren’t powerless either. Acting on your desires puts you in touch with them—otherwise, you have to put the same energy into disavowing them. Skip down the street if you’re happy, burn down a building if it outrages you. Love blossoms on a battlefield—it’s easier to release yourself to it when you’re ready to back it up! When you live out your own most secret wishes, you’ll find you express those of others, too. Find yourself projects that engage you, that put you in situations in which you are wholly present in the moment. And don’t be afraid of being unrealistic—it is precisely the unreal that needs realizing. You can’t create unless you can dream.

Create momentum! Anarchists don’t give instructions—we give license. Help others give themselves permission to live, by setting precedents—and offer support, share skills, create opportunities for the civilians around you to express their own radical desires in action. You’ll be surprised who will fight the pigs in the streets, when the chance arises!

Don’t sighingly sign petitions, pose for the cameras, await some window of opportunity. Do participate in town parades and street festivals, break into abandoned buildings to throw great banners down the sides, start conversations with strangers, challenge everything you thought you knew about yourself in bed, maintain a constant feeling in the air that something is happening. Live as if the future depends on your every deed, and it will. Don’t wait for yourself to show up—you already have. Grant yourself license to live and tear those shackles to ribbons: Create momentum!

Beautiful Anarchists Desire You

These days it can be difficult, even terrifying, to be an anarchist. You may well be one of those people who hides her anarchism, at least in certain situations, lest others (equally scared, and probably by the same things) accuse you of being too idealistic or “irresponsible”—as if politely burying the planet in garbage isn’t!

You shouldn’t be so timid—you are not alone. There are millions of us waiting for you to make yourself known, ready to love you and laugh with you and fight at your side for a better world. Follow your heart to the places we will meet. Please don’t be too late.

OK, I’m interested. What do I do next?

Not to be brusque, but haven’t you been paying attention? We’re not trying to get you to convert to a religion or vote for a party here—on the contrary. The best and the hardest part of this is that it’s entirely in your hands.

Rousing Conclusion

In some moments, in this insane world, anarchy appears in fragments, whispering of hidden lives that beckon from within this one: those hours you spend with your best friends after work, the remains of a poster pasted on an alley wall, that instant masturbating or making love when you are neither male nor female, fat nor skinny, rich nor poor. In other moments, that insanity is the exception, the fragment, and anarchy is simply the world we live. One hundred thousand of us can found a new civilization, one hundred can transform a city, two can write the bedtime stories our children have been waiting to hear—and sow the seeds for millions to come.

When one of us defies the protection racket of public opinion and “necessity” and drops everything to live as she has dreamed, the whole world receives the gift of that freedom. When we fill the streets to dance and blow fire, we can remember with our bodies that we deserve such dances and such space for them. When the ski resorts burn and department store windows shatter, for a moment “private property” is neither private nor property—and we create new relations between ourselves and a cosmos that is suddenly ours, and new, once more. If we risk our lives, it is because we know only by doing so can we make them our own.

See you on the front page of the last newspaper those motherfuckers ever print—

Noam Deguerre, CrimethInc. Writers’ Bloc

Appendix: A Genealogy of Force

A Fable

In the beginning, harmony: communities of human beings live as one, gathering and eating and playing and sleeping and singing and making love and telling stories together. And, occasionally, discord: an argument breaks out, strong words are exchanged, a blow is struck.

When this happens, the community meets and arrives at a resolution. Communities that cannot do this break up, and the members starve or freeze or are hunted down by wild beasts, or join another community that can resolve conflicts. Conflicts between communities are resolved in a similar manner. For thousands upon thousands of years, this way of life works and endures.

But one day, some cultural or technological innovation enables one group to accumulate power in such a way that they do not have to concern themselves with resolving conflicts—they can offload the negative consequences on others. Now discussion, placation, even combat do not serve to conclude hostilities; the combatants do not find their way back to peace as the others did before, but seek only to obtain more power. Intent on controlling and dominating others, even at the cost of their own happiness or safety, they become machines of war.

Their relationship with the environment shifts: the earth must be disciplined, now, to provide them reserves of food to last through their struggle. Their relationships with each other change: they evaluate others as potential comrades-in-arms or enemies, appraising might above all other qualities.

The neighboring communities do not escape unscathed. Soon they are embroiled in this struggle, as well, and must contend with an enemy such as they have never encountered. Many of these communities perish outright; others, determined survive at any cost, find that they too must become war machines. They too subjugate the earth and its animals, enslave their vanquished foes, even their own people, anything to endure in the face of this terror. They become the terror, they outdo it, and this is their undoing.

Spreading like a cancer, from community to community, strange changes sweep the face of the earth. Little communities merge to become big communities, and ultimately nations; temporary military leaders become hereditary monarchs; the vision of once peace-loving peoples becomes clouded with carnage.

And it is not only in military matters that these communities change. Territory is claimed and marked, and becomes the source of new conflicts. Patriarchy appears: the undeclared war between the sexes, the gendered roles of warrior and servant, institutionalized and enforced by each generation on the next. Market economics arises: peoples who no longer trust each other insist on trade where gifts once sufficed—and scramble to outwit each other, to profit at others’ expense even in peacetime. Organized religion is invented: now men not only vie for land, food, property, and power, but also to govern each other’s minds and hearts.

All of these innovations are catastrophic for human beings. They try to offset the effects with new innovations, and the new innovations prove to be greater catastrophes. Governments, convened to protect peoples, extract taxes from them and thrive idly off their sweat and toil; police fill the streets to prevent crime, and perpetrate worse crimes with impunity. Defending themselves from the monstrosities of civilization, these peoples breed more awful monsters.

Minor nations, hell-bent on withstanding the assaults of greater ones, arm themselves to the teeth—and go on fighting and conquering in exaggerated response to the original threat until they become great empires. So the Roman Empire finds its origins in the resistance of rural farmers to Etruscan encroachments; so the rest of Europe becomes a snakepit of competing empires, as a consequence of hundreds of years spent fighting Rome. Later historians will look at the bloody wars waged on the edges of every civilization as evidence that the “heart of darkness” beyond this frontier is a bloody barbarism; but perhaps it is the peace-loving barbarians who are defending themselves from the bloodthirsty. The true heart of darkness lies at the center of these empires, in the eye of the hurricane, where violence is so deeply ingrained in human life that it is no longer visible to the naked eye: slaves go about in the streets as if of their own volition, powerless even to rebel; gladiators slaughter each other in the circuses and it is called entertainment.

The next military campaigns are a symptom of social viciousness, not just a cause. Now the invisible violence of economics ordains the visible violence of armies: soldiers cut paths into the last wilderlands of barbarism so further resources can be seized by merchants, and the freshly destitute barbarians become a new consumer base. Whole continents are despoiled and the inhabitants enslaved—and then the looters cite their destitution as proof of their racial inferiority! Missionaries are in the front lines of the assault, enforcing the reign of the jealous One and Only God as surely as the soldiers enforce the reign of brutality. Terror for territory, blood for money, money for blood, He ordains it all—as it ordains Him.

The successors of the missionaries pray directly to the market. These new priests are even more successful than the soldiers in imposing the rule of power: a day comes when shackles are no longer needed to keep the population servile, when idolatry alone is enough to keep people fighting amongst themselves. Now no one can remember any other life, and son fights brother fights father fights neighbor, as the specters of fear and avarice look over their empire from above. Kings, generals, presidents rise and fall, but the system, hierarchy, remains: competition itself holds the crown, picking and discarding its champions without pity.

Everyone in these relationships of violence still wants, desperately, to escape, but again and again they bear the seeds of this violence with them, destroying every refuge as they enter—as the refugees who flee to the “New World” do, and the Communists who overthrow the Tsar. Even those who do escape, like the artists whose communes gentrify neighborhoods, whose provocative innovations set precedents for the next generation’s fashion photography, only pave the way for the steamrollers that follow in their footsteps.

Violence reaches an all-time high. Schoolchildren, mailmen, formerly the very picture of sociability, begin to gun down their companions in cold blood. Ministers molest altar boys, fathers batter their daughters, teenagers rape their dates. Prisons overflow. Millions perish in holocausts, and the maimed survivors initiate subsequent holocausts. Nuclear missiles point at everyone until the imminence of the final holocaust can only be discussed in platitudes. Now we are all on death row, all political prisoners. Even in the loftiest citadels of the United States, protected by the most sophisticated and well-equipped military in the history of the solar system, white-collar workers with full benefits and health insurance are no longer safe—airplanes crash, skyscrapers fall. Terror threatens us all.

Tonight a Palestinian youth struggles to work out the equation: have his enemies filled his world with enough misery that he feels more hatred for them than he does love for life? He thinks of his crippled father, of his bulldozed house, of his departed friends—who computed this same equation daily, always coming to one conclusion, until the day they came to another.

Where, through all this, is love? It is still here, in the forms it has always taken: families eating together, friends embracing, gifts given simply for the pleasure of giving. We still forgive, converse, fall deeply in love; it even happens occasionally that new communities federate to confront a common antagonist—not out of malice, but for the sake of peace, hoping to resolve conflicts as they were resolved in the days before warfare and commerce. These moments, even when they occur between only a few individuals, are as powerful and precious as they ever were. And they are still infectious, as infectious as violence and hatred, if only they can find unarmored hearts in which to catch hold.

The world now waits for a war on war, a love armed, a friendship which can defend itself. Anarchy is a word we use to describe those moments when force cannot subdue us, and life flourishes as we know it should; anarchism is the science of creating and defending such moments. It is a weapon that aspires to uselessness—the only kind of weapon we will wield, hoping against hope that this time, through some new alchemy, our weapons will not turn on us.

We know that after “the” revolution, after every revolution, the struggle between love and hatred, between coercion and cooperation, will continue; but, then, as now, as always, the important question is—which side are you on?